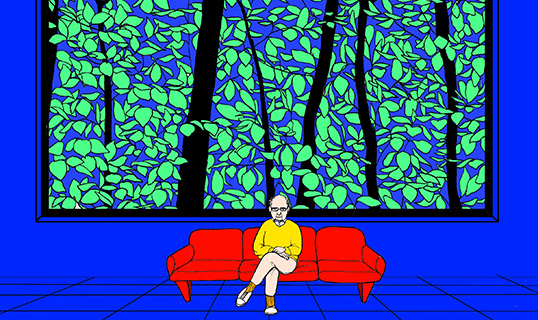

Andrés Sánchez Robayna’s poems are a treat — in delicately constructed verses, they evoke deeply visual associations. The lines are startling in their clarity, and yet succeed in wrapping the reader in their complex ambiguities.

The Sleeper Who Heard the Most Diffuse Music

The delicate backstrokes of sleep

rise red over the ocean,

thick, warm clouds

on the far side of the vaulted day,

the sea in this summer breeze.

The most diffuse music, in a dream,

the most intense vision, he dreams

the ebbing waves, the sun, the pines

twirling amidst these swells and drafts.

His back dissolves into clouds.

Neither the sun nor the dawn will be for him

the illusion of sun or dawn or blue.

On a Swimmer’s Shadow

not in living rock: out of granite

sculpted angles of the pool

the shadow on the mosaic below

sketches the figure above

far away, the shapeless clouds

slide off at their leisure

in the blind light of the edges

labile light, still shadow

so his written body flees

sculpted thus, the light dives deep

Translations from the Spanish by Arthur Dixon & Daniel Simon

Editorial note: From Al cúmulo de octubre: antología poética, 1970–2015 (Madrid: Visor Libros, 2015). Translated by permission of the author.

A prolific author, editor, critic, and translator, Andrés Sánchez Robayna has published more than sixty books of poetry, essays, and translations. He completed a PhD in philology at the University of Barcelona in 1977, directed the magazines Literradura and Syntaxis, and is currently professor of Spanish literature at the University of La Laguna.

Arthur Dixon works as a translator and as managing editor of World Literature Today’s affiliated journal Latin American Literature Today. His translation of Andrés Felipe Solano’s The Nameless Saints (World Literature Today, September 2014) was nominated for a 2014 Pushcart Prize. His most recent project is a book-length translation of Arturo Gutiérrez Plaza’s Cuidados intensivos (World Literature Today, September 2016). He is Asymptote’s Spanish Social Media Manager.

Daniel Simon is a poet, translator, and the editor in chief of World Literature Today. His latest verse collection, After Reading Everything, has been nominated for the Forward Prize, the T. S. Eliot Prize, a Pushcart, and several other awards. His translation credits include Ramón Gaya, Eduardo Mitre, Mario Arteca, José Mateos, Abdellah Taïa, and Boualem Sansal.

*****

Read more translations: