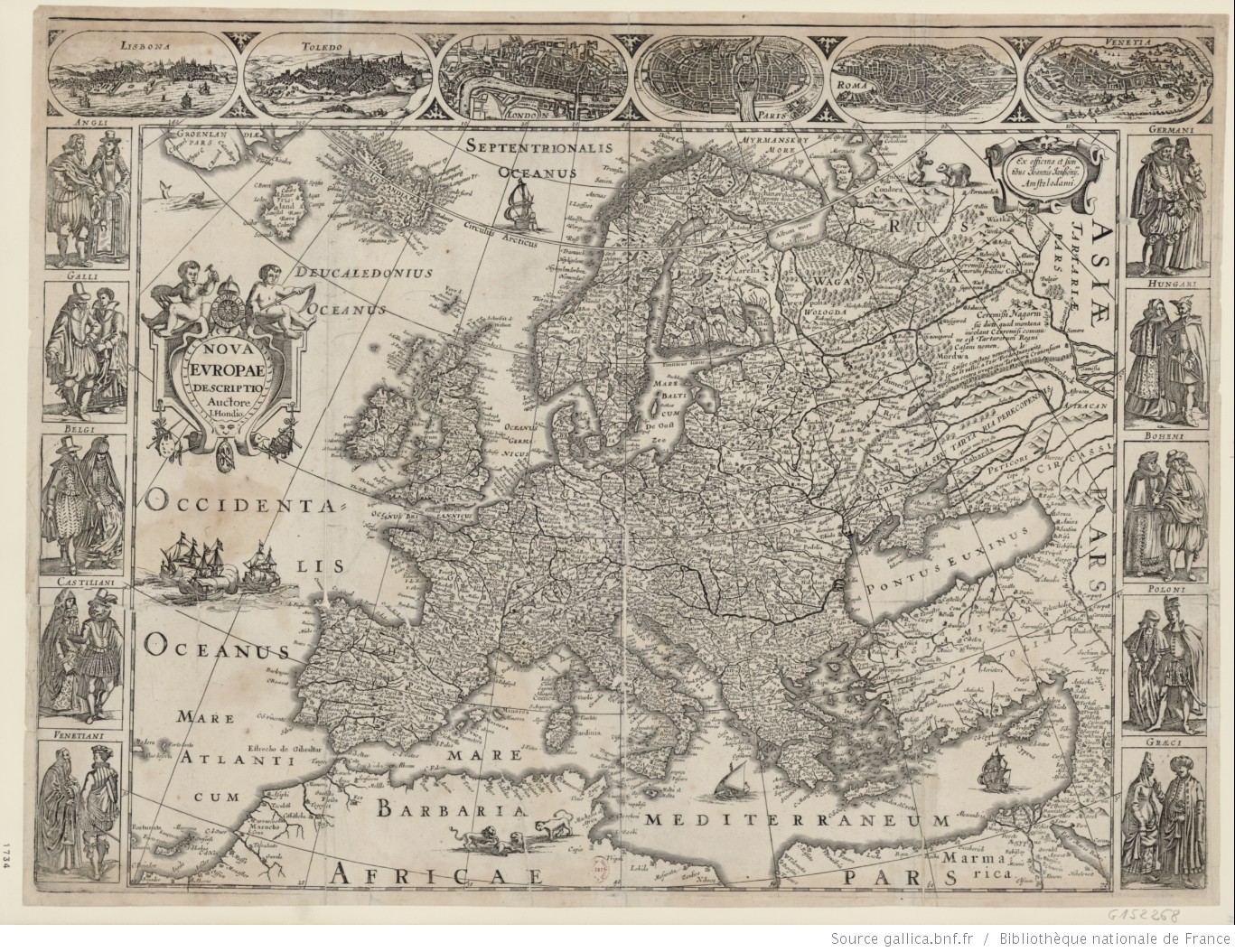

Zsuzanna Gahse’s strange and eloquent meditation on the question of what, or rather, who “Europe” is has only become more relevant over the course of the past year in politics. Gahse’s Europe is the continent that shares her name with a princess abducted by Zeus. “Europe consists of its disintegration,” she writes. Gahse’s writing is all the more relevant for not being “topical”: these prescient thoughts on Europe’s disintegration date from 2004, the year of the EU’s most ambitious expansion. Her Europe is composed of a collection of accents, languages, and landscapes, “a collection of mountain ridges wrinkling the earth.” It’s an Europe for travellers, migrants, and lovers.

Her first book to be published in English comes out this month with Dalkey Archive in Chenxin Jiang’s translation. The translator and writer spoke shortly before the book’s release.

Chenxin Jiang (CJ): The Süddeutsche Zeitung wrote of you a few days ago: “As a master of short prose, she has become a truly European author.” Is the short prose form central to your being a European author?

Zsuzanna Ghase (ZG): Short compact narratives and even individual sentences can be memorable and indeed arresting. Whether in prose, poetry, or drama, these types of writing have a remarkable role to play in the modern world, and the endless (serious and unserious) ways of playing on them constitute an experimental challenge. As for being a European author, I certainly am one, in that I don’t focus on any one country (or my so-called “own” country) in my books, but am interested in many different countries.

CJ: In what sense are the pieces in Volatile Texts part of what the first piece would call “a collection”?

ZG: The word “collection” only applies to the first piece in the book and the pictures of Europe it presents. Europe can be described as a collection of various customs and histories, different languages, climates, political arrangements and so on; a collection that is both well- and less-than-well-developed. You could spend a long time surveying the cuisines alone. All that taken together is Europe: in other words, a collection.

But the individual pieces in Volatile Texts are carefully composed. As such, they do not constitute an arbitrarily assembled collection—hence the subtext of Europe that runs throughout. The fact that a Hamburger can become a Roman and a woman from France an American in one of the Volatile Texts speaks to the porousness of identity, to the existence of a collection of identities.

CJ: In Volatile Texts, you write that “languages [are] shaped by landscape, by topography.” How has your own attentiveness to language and your writing been shaped by living in Switzerland?

ZG: In the mountains, in order to make yourself understood between the cliffs, you need a different voice from the voice you’d use on the plains. It must be true in the Rockies too, that voices have to prevail against the mountains. Conditions are different on the tranquil plains: for instance, in windswept northern Germany, I’ve observed that people talk with a distinct singsong, so that the wind doesn’t take all their syllables and sounds with it. The striking number of phonological shifts in Swiss German, which might have to do with the topography of the landscape, has always interested me—not to mention the fact that Switzerland has four languages. Because of these linguistic boundaries and the different regions within Switzerland, I began playing with the idea of depicting Switzerland, of all places, as Europe—since, as you know, Switzerland is part of the continent but not part of the EU.

READ MORE…