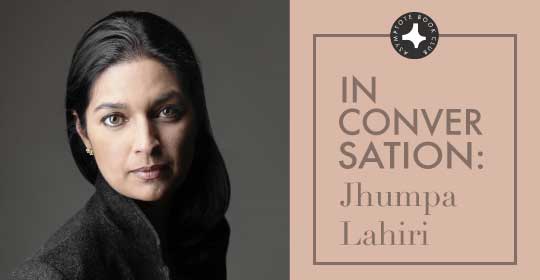

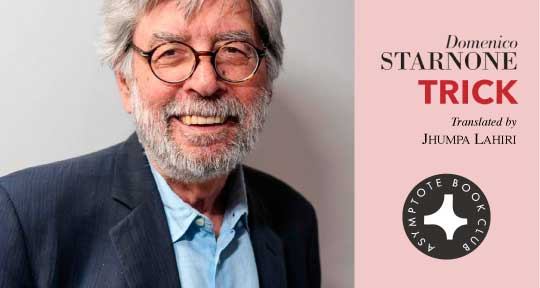

In our fourth Asymptote Book Club interview, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri spoke with Asymptote Assistant Editor Victoria Livingstone about her translation of Domenico Starnone’s Trick.

In this discussion about her work and the forging of her own artistic identity, Lahiri reveals why translating Starnone seemed like “a sort of destiny.” Lahiri draws us into Starnone’s fictional world, but also reflects on her own mutable relationship with language and writing, and on the marvelous yet precarious ways in which our lives unfold.

Victoria Livingstone (VL): I wanted to begin by asking you what brought you to translation. I just finished reading In Other Words in which you reflect on your decision to switch from writing in English to writing in Italian. Did you see translation as a natural progression after working between multiple languages and living in Italy? And what drew you to Domenico Starnone in particular?

Jhumpa Lahiri (JL): During the initial part of my stay in Italy, I wanted to translate something, but I didn’t know what it would be. I was reading only in Italian for many years. As my reading progressed, I would think that I would like to translate this person, or that person. Once my Italian was stronger and my reading in Italian seemed to have a larger ongoing purpose and focus, translation was something that really intrigued me.

I was considering it in this vague way and then I read Lacci by Domenico [Starnone] and immediately felt that if I were to translate something, that this would be the book I wanted to translate. I felt very close to it. It spoke to me very deeply. It felt like the natural first step. That’s how it started. When he asked me to translate the book, we were already friends and I felt—I feel now—that it was a sort of destiny. Everything was properly aligned in the moment that I was drawn to the idea of translating and was ready to translate with the appropriate amount of distance. That was when Lacci, which became Ties, won a prize which enabled the translation to be funded. It was a series of fortuitous circumstances that led to the translation of that book a couple of years ago.