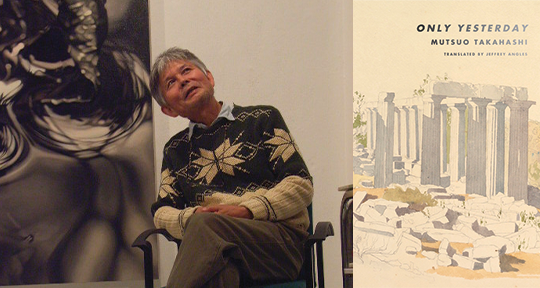

Only Yesterday by Mutsuo Takahashi, translated from the Japanese by Jeffrey Angles, Canarium Books, 2023

Classicists are not known for pared-back prose, but in the June 1936 edition of The Classical Journal, Hanako Hoshino Yamagiwa penned a candid, simple piece on the multiple, “surprising” similarities between Ancient Greece and the Japan of her time—a comparison drawn not through extensive research, but the “things which I actually saw, heard, or read from my childhood”. Published for its novelty more than its expertise, this quiet, strange essay touches on a myriad of surface resemblances: agricultural practices, the affinity of Athena and Amaterasu, the lack of romance in marital matters, the habit of passing things from left to right. Together, these daily observations hint towards a woman who, while reading about a nation that could not be further away, had seen a vision of her own life. And so, what emerges is not a convincing portrait of how these island countries may mirror one another between their spatial and temporal distances, but testimony for a vaster pattern: the travelling body hunting the ontological material of geography to retell history, to excavate an expression of the self from the mired cliffs and centuries. It is the story of a body curious, remembering, and in motion. Its muddied tracks.

In Mutsuo Takahashi’s Only Yesterday, Greece is the poet’s material, base, and centre. Through over one hundred and fifty short poems, each translated with much care and expertise by Jeffrey Angles, the poet casts upon shores and mountains, daybreaks and cicada-filled treelines, portioning out a lifelong fascination with the archipelago and all that links it to the world. An extensive corpus has already attested to the depth of Takahashi’s affinity for the Hellenic—from translations of Euripedes and Sophocles to a repertoire of essays and interpretations—but this collection, largely written in his seventy-ninth year, is the first to be entirely dedicated to Greece. And perhaps it is because of this timing, in the winter of the poet’s life, that the view presented in these brief lines is not one of raw precision, of wandering or travelogue, but of Greece dissolving, slowly, into the liquid called reflection.