Translated into English by Beigbeder’s frequent collaborator, Frank Wynne, A Life Without End tells the story of “Frédéric Beigbeder,” a successful yet jaded television host who, upon turning fifty, decides he wants to live forever. Accompanied by his daughter, Romy, partner Léonore—a geneticist, and their vociferous robotic companion, the fictional Frédéric travels the world visiting labs and clinics, interviewing researchers, geneticists, biologists, and doctors in pursuit of eternal life.

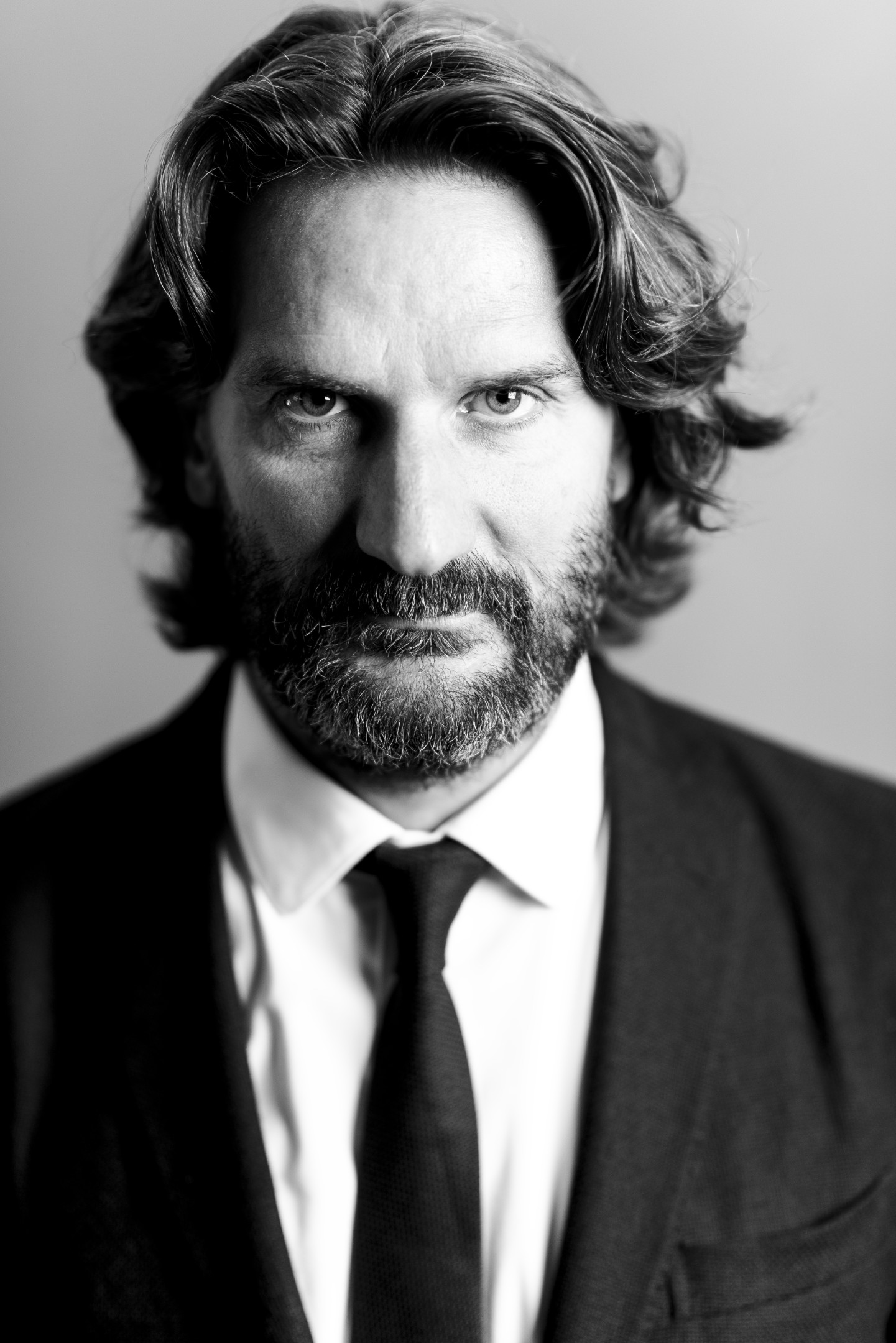

The “real” Beigbeder, once frequently labeled the enfant terrible of French literature, is the author of several works, including 99 Francs (published in English as £9.99 and translated by Adriana Hunter), Love Lasts Three Years, A French Novel, and the award-winning Windows on the World, all translated by Frank Wynne. Known for his provocative wit, a fondness for mixing fiction with facts and self-parody, his columns in Le Figaro Magazine, and frequent television appearances, Beigbeder also founded the Prix de Flore, a French-language literary prize for emerging writers, awarded annually since 1994. More recently, Beigbeder published Oona & Salinger, a biographical novel about the relationship between J.D. Salinger and Oona O'Neill, before embarking on the research that would form the basis for A Life Without End.

For centuries, writers and storytellers around the world have imagined and grappled with the prospect of human immortality. From The Epic of Gilgamesh to Kundera’s Immortality and Atwood’s Oryx and Crake, fiction has offered us a space to safely explore the potential benefits, disadvantages, and ethical and social considerations related to the pursuit of eternal life. But over the past decade, scientists and entrepreneurs have developed a range of technologies and interventions that wouldn’t seem out of place in the most fanciful works of speculative fiction. And it is these advancements in cryonics, transhumanism, and synthetic biology that Beigbeder seeks to interrogate in A Life Without End. After a series of interviews at real clinics and research facilities around the world, Beigbeder shrewdly volunteers his wealthy, white, male fictional double as an all-too-willing guinea pig for the various therapies and treatments on offer. In contrast, his geneticist partner, Léonore, decries the experimental therapies as “just a fantasy designed to humor infantile, ignorant, narcissistic megalomaniacs.”

On May 30, NASA and Elon Musk’s SpaceX launched two men into space amid a global pandemic, as historic Black Lives Matter and anti-racist protests, prompted by the murder of George Floyd, took place across the United States. As I watched the launch, I could not help but recall the many questions raised by Beigbeder’s journey in A Life Without End. Who is initiating and financing these scientific advancements? How are they regulated? Who benefits from them and who is forgotten? As humankind continues to “advance,” what is left behind? I wanted to learn more about Beigbeder’s experiences with the individuals and institutions at the forefront of life prolongment interventions, immortality research, and bioethics. I also wondered if the coronavirus pandemic had changed his perspective on any of the scenarios explored in his “science nonfiction.” When I reached out to Beigbeder, he wrote back suggesting that it was the perfect time for a conversation about “the apocalypse” as both of us were in lockdown, due to the virus. The following interview was conducted via email over the course of a few eventful weeks in the middle of 2020.

—Sarah Timmer Harvey

Are you in Paris now? How has the lockdown been for you, and how have you been spending your time?

No, I live in Guéthary, a small village on the Atlantic coast, near the Spanish border. I left Paris three years ago to fly away from the pollution, stress, self-destruction, madness, and speed of the city. I don’t regret it. Being locked in a house with a view of the sea, a beach, a garden, and a pool makes me the luckiest prisoner on earth. I wish I could answer that I was reading, writing, and listening to intelligent people all day long, but that wouldn't be true. I have three children: two, four, and twenty years old. It’s left me no time to create, and I feel very ashamed and guilty for saying this but these were the happiest two months of my entire life. I’ve been locked up with my three children and my wife with an excuse to do absolutely nothing else other than cook, play, teach, and take care of my family. I know this might sound like a nightmare for many men, but not for me.

A Life Without End follows a man whose midlife crisis propels him into a globetrotting quest for immortality. Was the story as it appears in the novel always your intention for this project, or did your research into the area of life prolongment and transhumanism birth the idea for the story?

I’ve always studied these subjects, but this time, before starting to write, I spent three years traveling around the world. I went to Switzerland, Austria, Israel, and the United States. I met several scientists: geneticists, biologists, specialists in stem cells, and heads of laboratories. I asked all of them the same question: “How can I become immortal?” I tried different protocols and experiments—sequencing my DNA and having my blood rejuvenated, which was both fun and scary. Then, I decided that my book was to tell the story of the three years of this quest. That’s why the character has my name.

A Life Without End opens with a reflection on selfies and the new order they have created. You describe social media as a “war” on anonymity in which the “winners snub the losers” by “maximizing their share of public love.” But now we find ourselves in the corona era, are you engaging with social media and selfies differently? Do you see the purpose and perception of the selfie changing?

I am not on social media. I still hate it. I think it’s stupid, narcissistic, and dangerous. It drives everybody crazy, makes people lonely, full of hate, and frustration. I really don’t understand it. If I want to talk to my friends, I’ll call them on the phone or send emails like this one. I don’t need to take pictures of my life and expose them to the rest of the world. It’s absurd, and I am too lazy to do it. I prefer to expose my life in my books!

Can we talk about that? While many writers are keen to distance themselves from the characters in their work, or at the very least try to mask the parallels, throughout your career, you have deliberately mixed fiction with reality. Despite its title, your 2009 book, A French Novel, was actually a memoir. In A Life Without End, your main protagonist is called Frédéric Beigbeder, and his life is similar, though not identical, to your own. What do you find interesting about playing with the reader’s understanding of the “real” Frédéric vs. the fictional Frédéric?

My problem is that I have no imagination. I use my own experience to write fiction. So I start from my personal life, and then transform, elaborate, imagine, and the memoir slowly becomes fiction. In A Life Without End, the first half of the novel is completely true, but the second part is almost a science-fiction movie. I like to pretend to write a diary and then make up things. Many of my favorite novels use this structure, for example, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley. I know that Americans like to separate fiction and nonfiction, but I enjoy mixing both. To be honest, I think novelists are a bunch of liars. And the best liars are the ones who sound completely sincere.

A lot of the companies, institutions, and people that you depict and quote in the book are also real. Yet, some of the research, therapies, and techniques your book explores are legally and ethically questionable. Did any of the people or organizations you interviewed have concerns about how they would be represented in your writing? Or in this particular industry, did you find that the idea of all publicity being good publicity prevailed?

You’re right. The companies, the people, and the places in A Life Without End all exist; it’s easy to fact-check it. The conversations with the famous doctors that I met are also real. I kept all the recordings in case anyone wants to listen to them. But then, I didn’t visit them with my daughter and a Japanese robot—this part of the novel was fiction. Neither did I inject young blood in my veins or ask for my brain to be transplanted into a computer. The reader has to guess what is journalism and what is fantasy or lunacy. I didn’t prank anybody; I simply asked some clever scientists a lot of questions and they were all aware they would become characters in a mad French novel about eternal life. I never pretended to be a serious reporter from The New York Times!

One of the companies your main protagonist visits in A Life Without End is Cellectis, a gene-editing company whose motto is “Editing Life.” In your opinion, is editing a “life” the same as editing the human body?

Editing “life” is certainly possible now. If there is a vaccine for COVID-19, it will probably be the result of changing DNA (the human genome). Thousands of laboratories all over the planet are “editing” (i.e., modifying, “improving”) human DNA as we speak. There are even 3D printers that use human cells! The idea that the homo sapiens body should be holy and respected is a dead idea, something I did not imagine when I started working on this topic. But it’s the most frightening part of my quest for immortality. The creation of a new humankind already began ten years ago, and still nobody seems to care about protecting the human race. In order to live longer, we have already created the posthuman.

There are some interesting reflections on bioconservatism in the novel. For example, your main protagonist fails to convince his parents to have their brains transplanted into a biomechanical body. Your protagonist cannot understand their resistance, given that they already have a coronary stent and polyethylene kneecaps in their bodies, and he doesn’t see the difference. Elon Musk claims that due to handheld intelligent devices, humans are already on their way to becoming cyborgs. Do you think this is true? Do you believe that we already crossed that line when we gained the ability to implant artificial organs and prostheses into the human body? Did it change when we became dependent on handheld devices, or do you think it is a line humans have yet to cross?

The line was crossed a long time ago. Implants and prostheses were just the beginning. Now we accept that we are giving all the data on our private lives to a few companies. Elon Musk is a madman when he talks about colonizing Mars, but when it comes to transhumanism he is absolutely right. The next step is to integrate the digital world into the human brain. Once this is done, there will be no turning back. The superheroes of Marvel comics aren’t just funny blockbuster characters for teenagers; they are precise and accurate renderings of our future. We will become half-human, half-machines—we already can’t live without smartphones. Imagine having enhanced bodies with titanium skeletons, communicating with brains directly connected to Google. When you have this, Google will own you. In fact, they already do. Google knows every porn movie you’ve watched since 2004.

Manfred Clynes, the man who first coined the word “Cyborg” in 1960, envisioned it as a way of “enlarging the human experience.” Not “less human, but more.” Do you agree with Clynes?

No, I don’t. I also dislike Yuval Harari’s idea of “Homo Deus.” Why? Because I am glad to be an old mammal with failures, weaknesses, a vintage homo sapien. I like that my thoughts are only mine. I like to have secrets and privacy and don’t want to have a GPS spying on me everywhere I go. I am proud to be human, even if humans have many limitations. I’m a paranoid French writer and don’t want to become a robot or an algorithm. I want to love, have sex, eat and drink like a mammal. Essentially, I wrote this novel because I am terribly afraid of death. But let’s be frank: in the last three months, the whole planet has willingly given up freedom just to be protected from a deadly virus. Well, now, this has opened my eyes. I accept death. I prefer risking my life for freedom. To me, freedom is more important than longevity. Being a human with a short life expectancy is so much nicer than being a machine or a zombie hiding in a basement, watching Zoom all day.

There are several speculative passages in A Life Without End, exploring what humankind and society could look like in 2033, 2051, and even this year, 2020. Now we find ourselves in the middle of a global pandemic, which will clearly have an enormous effect on humans around the globe. In 2003 you wrote Windows on the World after 9/11 because you “couldn't see the point of speaking of anything else.” Do you feel equally compelled to write about this world event?

I am afraid that there will be millions of books about this lockdown, and I am too much of a snob to write one of them. Windows on the World was a different kind of project. Nobody wanted to write about 9/11. It was taboo. And like a spoiled child, I like to disobey. But I do hope this experience of 2020 will change the minds of many humans worldwide. For example, understanding that eating food produced and made in your neighborhood is simpler and better. Knowing that we don’t need to use planes every day. Swapping your petrol-guzzling car for an electric one. We all know that this was an alert, but not an isolated incident—AIDS has killed at least twice as many people as COVID-19. But it was a sign that it’s time to protect what we like in our lives. Not only nature but also our freedoms and cultures. Things like cinema, parties, drinking caipirinhas, and kissing in the street. These are small but important liberties, and right now, I feel we will have to fight to win them back.

Can you clarify what you mean when you say “we’ll” have to “fight”?

To protect my health, the government has destroyed my way of life for three months. I want my life back! To me, freedom is more important than security. I am scared of a sort of “health dictatorship” that could last forever. I don’t think the role of a politician is to protect the citizen. The government should not act as if it was my mother.

The climax of A Life Without End takes place in America. Why was it important to have your characters “transforming” in this particular setting?

America is where all the craziest and most powerful transhumanists live. When you are looking for vampires, you go to Transylvania.

You have previously said that writing is a better way to explore taboos because it can go where television and film cannot. The fictional Frédéric Beigbeder spends a lot of time coming up with boundary-pushing ideas for television; live drug use, sex, and even death. Given that streaming has changed the way we consume visual entertainment, do you see any of the wild ideas proposed in the book becoming reality?

Haha! I think there are already TV shows where the guests are using drugs but not officially! I am quite sure that my wildest ideas will eventually be produced. My experience working in TV sadly proved to me that some producers have no moral issues as long as they can get good ratings.

If you believe all novelists are liars and TV is run by producers who will do anything to get ratings, do you think there is anyone in the creative world that is telling the truth? What is truth to you?

I will quote one of my favorite French poets, Jean Cocteau. He said, “I am a lie that always tells the truth.” That’s my definition of literature: a lie that tells the truth.

Do you read the finished translations of your novels? And did you work with Frank Wynne on the translation of A Life Without End?

Of course! It’s a pleasure to work with one of the best translators working in my language. He sends me emails whenever he has doubts, and we talk on the phone. We’re friends. Together, we received the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for Windows on the World. I know that I will never receive the Nobel Prize but this was my Nobel! It is a great honor that created a bond between us. In my speech at the ceremony, which was held at the National Gallery in London, I said “Frank improves my work.” And I still think he does; I’m very lucky to have Frank.

Controversially, the English translation of your novel 99 Francs was completely anglicized. Even the setting was changed from France to London. What did you think of this choice?

Allowing it was a huge mistake. That translation is a painful souvenir. I changed my publisher after that happened. I should have refused, but I was young and foolish. André Gide accepted cutting the sexual parts in some of his English translations, and I knew this before I was asked to censor myself. So, it’s Gide’s fault! We poor French novelists, are begging English speaking countries to read us; we would accept anything to exist in your xenophobic reading culture.

Do you think that the French literary world is less xenophobic than its English-language counterpart?

Being translated into English is the dream of many French artists because we admire English and American culture. I don’t think English literature is xenophobic, but English readers are. In France, we worship all English and US novelists. In England and America, nobody cares about French books. It’s very sad, but true. The French love you, but it’s not reciprocated.

So, after the 99 Francs debacle, it’s become more important to you that translations of your work retain French cultural and linguistic elements?

Of course, it’s essential that my antiheroes are French. There’s a reason they’re so obsessed with wine, sex, food, and love (in that order). It’s all the happiness robots don’t care for.

Do you mean that the French antiheroes you write are the antithesis of robots?

Exactly. You understand me very well.

In 1994, you founded the Prix de Flore, an annual prize for emerging French-language writers. What motivated you to create the award? Do you have any advice for young writers hoping to win it?

Twenty-six years ago, the kind of novels I loved were totally ignored by the French literary prize juries. Houellebecq, Despentes, Nothomb, and I were a group of ambitious young writers and we wanted to conquer the world. Finally, we conquered Saint-Germain-des-Prés and now we are all rich and famous. If I have any advice to a young brat like I was in those years, it would be this: Don’t listen to my advice. Create your own prizes, your own literary reviews, write your own books, and kill off the likes of me.