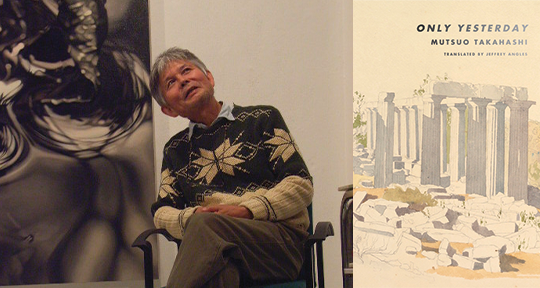

Only Yesterday by Mutsuo Takahashi, translated from the Japanese by Jeffrey Angles, Canarium Books, 2023

Classicists are not known for pared-back prose, but in the June 1936 edition of The Classical Journal, Hanako Hoshino Yamagiwa penned a candid, simple piece on the multiple, “surprising” similarities between Ancient Greece and the Japan of her time—a comparison drawn not through extensive research, but the “things which I actually saw, heard, or read from my childhood”. Published for its novelty more than its expertise, this quiet, strange essay touches on a myriad of surface resemblances: agricultural practices, the affinity of Athena and Amaterasu, the lack of romance in marital matters, the habit of passing things from left to right. Together, these daily observations hint towards a woman who, while reading about a nation that could not be further away, had seen a vision of her own life. And so, what emerges is not a convincing portrait of how these island countries may mirror one another between their spatial and temporal distances, but testimony for a vaster pattern: the travelling body hunting the ontological material of geography to retell history, to excavate an expression of the self from the mired cliffs and centuries. It is the story of a body curious, remembering, and in motion. Its muddied tracks.

In Mutsuo Takahashi’s Only Yesterday, Greece is the poet’s material, base, and centre. Through over one hundred and fifty short poems, each translated with much care and expertise by Jeffrey Angles, the poet casts upon shores and mountains, daybreaks and cicada-filled treelines, portioning out a lifelong fascination with the archipelago and all that links it to the world. An extensive corpus has already attested to the depth of Takahashi’s affinity for the Hellenic—from translations of Euripedes and Sophocles to a repertoire of essays and interpretations—but this collection, largely written in his seventy-ninth year, is the first to be entirely dedicated to Greece. And perhaps it is because of this timing, in the winter of the poet’s life, that the view presented in these brief lines is not one of raw precision, of wandering or travelogue, but of Greece dissolving, slowly, into the liquid called reflection.

Locations in poetry are never where the poems happen; they are a point of displacement, where one certainty is erased into another. Any setting introduced to the page can collapse at an instant into reverie: every house a dreamhouse, every configuration a phenomenon. In the hands of a capable poet, the proper noun soon empties out its contents to become a loose end, activating a sequence of revelations, and such is the imagination of place not as an end state—a physicality to be experienced or to hold experience—but an endless process of relations. Like the films in which a light is turned on, and suddenly the room is revealed to be far bigger than one expected, or a hallway much longer and unknowable, place is not a fixed arena, but a mechanism. Monuments and sights disappear with the break of a line, and a memory or a feeling takes its place. In Only Yesterday, one enters the soft arcade of Greece to find an argument, a ship lost in the waves, an overheard conversation. Greece, and those first familiar scenes of torn marble torsos, flights of native birds, half-moon glasses of wine seen in sunlight—turns out to be the corridors of one’s own memory, or a telephone by which beloved, dead poets are called back and spoken to again. “Before I knew it, the island of myself had become Greece”, Takahashi reveals breathlessly in the ninety-fourth poem. And we believe him, because by this point, we know that this country is not a country at all, but—as the poet will tell us himself, later on—the experience of poetry itself.

It doesn’t take much of a mental leap to see how Greece can be tuned as an instrument, and an enduring ars poetica articulated through it. The poems in Only Yesterday summon real trips taken, but what interests Takashi is the psychogeographic terrain—the distance between the country and its representation as artifact, translating into the distance between self and memory. Wielding epics and allegories, he examines what truths hold strong when the thickets of worldly argument grow around them; what happens between the design and the ruin, between history and its mythologisation; and most pivotally, what reins we wrap around time as we call the past back towards us, over and over. In “Greece & I”, the essay that acts as afterword, Takahashi thinks out loud: “If I were to hazard a guess as to why one can feel so close to things that happened so long ago, it probably has to do with the speculative abilities that the Ancient Greeks invented.” As he sees it, it is their insistence on the why—the persistent urge for learning—that keeps Ancient Greece alive in our cultural consciousness. And while it’s certain that Mutsuo Takahashi’s life is one that reflects a predilection towards maximalist learning (how else could the man have published over eighty books, sometimes three in one year?), another function of interrogation is clarified in these poems. For memory is the Proteus of our daily myth, a figure which shapeshifts so as to not answer questions, and when the past is endlessly malleable, evasive, providing no resolution—that is when it feels most urgent, contemporary, and here, in the present. To seek memory for an answer, then, is not to actually find it; it is instead an act that catalyses the past to transform and enter into a new state, thus briefly connecting it again to the asking present. In directing the why towards his memories, Takahashi searches their contours for something new. Like this, so simply, he folds time’s unforgiving continuum in one motion, collapsing it into that narrow, white space between one line and the next.

It begins with the first poem, “Early Summer 1969”, which deserves to be quoted here in whole:

At the top of the stone steps of the Acropolis, I head into the Parthenon

Lean briefly against a pillar before casting off on sandaled feet

I’d been reading Kitto’s The Greeks, and as I traced the lines,

I saw how ridiculous I was, feeling I’d turned Greek in some small way

Before I knew it, I was nodding off on sea breezes from far-off Piraeus

And in the rounds of sleep, the world was nothing but tenderness

Held in this soft world’s embrace, I felt as if I could do it all

I was young, so young, though it was only yesterday, or perhaps the day before

This dreaming, concluding line is echoed immediately in the next poem, which is titled, with striking contrast, “Twenty-Seventh Day, Fourth Month, 399 BCE”—the day of Socrates’ execution by hemlock. Here it is not one’s own youth but the philosopher’s final words that defy time, resounding as if they were said “only yesterday, or at most, a month before”. When these two poems are read in concert, what holds them together is an act of memory—an already slippery arrangement made even more so by the fact that “Early Summer” is written in the past tense, and “Twenty-Seventh Day” is written in the present: an interplay between recollection and exhibition. One is lived, and the other is simply restaged, yet both are placed within the same anachronous defiance. The only meaningful demarcation here, then, is not between the years or the lifetimes, but only between yesterday and today. What is thrown behind us into yesterday’s abyss is there forever; the past is a seamless slurry of yesterdays.

“History,” Walter Benjamin wrote, “is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogenous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now.” We can only ride into the past by way of the present, and when we ask why of its blurry reconstructions, we are transported not backwards but deeper within. In these poems, the elastic language of time constantly reformats the frames around any single experience, allowing a stream of newly arriving thoughts to ripple the surfaces. Sitting in Syntagma Square, the poet, with a glass of wine and a plate of dolmades in front of him, thinks out loud about the name of the restaurant: “Aesop, of course, was the source.” For Takahashi, references such as this usually initiate a sudden departure. He narrates the half-formed beginnings of thought: “As I eat and drink, I think about cliffs. They say a crowd pushed Aesop off one / because of his constant lies, but what he shared were really truths”. Then the trigger flips. The poem develops self-consciousness, and the narrator no longer narrates but confesses: “Conversely, what I have written are lies pretending to be truths / Ones hardly worth being pushed off a cliff at all”. We have moved from name, to story, to lies, to truth—and it is one of the triumphs of this collection that a truth iterated, at the end of brief discourses and excursions, comes with a note of finality: the exhale of a finished speech. The fleeting thought concludes, the regular stream of reality takes over, and the spark that lit the brief poem has occurred and faded, just like an idea in the mind. This is not to say that the poems aren’t memorable, but that they procure a sense of imagination’s evanescent, shifty nature. The past does not stay with us for long; we seek to borrow its guidance, but what we receive is its fragility.

Future, too, stirs into these poems. The word “perhaps” appears often throughout the collection, in unrelinquished surges of wonder, and at its periphery is an overgrowing field of the unknown. Ultimately, it is the growing thought of death that has brought the poet to this edge, and certain verses integrate into the symbolic and textual body of Greece to dwell upon its many endings, both archeological and spiritual. There is the poet holding a pebble on Lesbos, trying impossibly to conjure up a history from that single, silent stone; there is Thanatos, looking much kinder and younger than the god of love; and there are the dead themselves, loitering about and quizzical at the sight of a funeral procession. The collection is not quite haunted, but a sinuous flow of bodies both anonymous and loved weaves through the text, along with what has continued to live on past them. In a poem dedicated to Borges, he writes: “For the first time in ages, I read you again today and realized / When we consume the water of immortality that is you, we cannot die”. Takahashi had previously commented on this collaborative praxis between poets in a piece from Shinchosha, mentioning that we have attributed both the Iliad and the Odyssey to a single author, Homer, despite the fact that these epics are composed of songs sang across generations. If we are to give the name Homer, then, to the author, there would be dozens, even hundreds of Homers—all of them persisting invisibly, woven inextricably into words. Drawing on rakugo, a form of theatre in which familiar monologues rely on a gifted storyteller’s delivery, Takahashi cloaks the relatively short span of human life with the exponentially longer existence of stories, underlining this multiple corporality, a small triumph over disappearance. So it is that death, in these partial and splintered glimpses, is more mysterious than terrifying, and worth thinking about as an ontological experiment: “Does that mean that in the next world, I’ll finally sleep my dreamless fill, / And melt into nothingness?”

It’s interesting, then, when tragedy is nowhere to be found in death, but the elegiac settles so intimately into the subject of aging. Where Only Yesterday is melancholic, it is often to do with the evidence of age, as incontestable as the boundary between today and yesterday. In poems such as “The Young and the Elderly”, Takahashi reckons with the disappearance that seems to be unwittingly cast on the old, grappling with the strange cost of the years—what they give, what they take—while imagining the generations in battle, with enforced invisibility as the most obliterating weapon. Though he speaks regretfully elsewhere of losing innocence and sexual recklessness, the utmost terror of aging is the fading away, the disappearance. It isn’t the lost objects that cause pain—for we know not what is gone—but the procession of losing. Here, Takahashi’s becoming of Greece displays its most powerful parallel: a country that has always used stories and poems to visualise its ruins as sites of glory, and a poet who now uses language and lyric to face again the architecture of his recollections, their “tender shadows”. A country that continues to enchant and be enchanted by its past and its beauty, and a poet who now walks himself backward, again amongst the “who-knows-who and who-knows-when”, enthralled by such transformations.

There’s a poem of C. P. Cavafy’s where he describes “the shape of an ethereal youth” that could be seen during August, sprinting in the hills of Ionia, after all the temples had been overtaken and the effigies destroyed. It was a sign—that the gods had not abandoned the world despite all the tumult and the betrayal, that the air still “pulses with their life”. Takahashi, in turn, tells us about a dream of being chased by an old man:

In the dream, I was the young man, but when I wake, I’m an old man

But truth be told, the old man chasing despite all demands and protestations

Must have been me—If so, then perhaps the fleeting youth was poésie itself

It is to speak a hope aloud that nothing abandons us: not our memories, not our past selves, not poetry—even if it is only in dreams and in shadowed thoughts. In its staging of these cycles, presenting what flits across time’s enormous fixtures, Only Yesterday forms a tenuous, earned syntax between somethingness and nothingness, youth and age, construction and ruin, the making of memories and the end of them—but still keeps in view poetry’s chimeric silhouette, slipping along the cliffs and looking to be chased. Yukio Mishima had once written to Takahashi, telling him that where a novel is ugly architecture fixed to the ground, poetry is a tower floating mid-air. We find ourselves there in this collection, hovering at the middle, stranded between looking backwards and looking forwards, and from this liminal space one finds a wonderment in the guise of an elegy, a question mark in the guise of a period, and a life in the guise of a philosophy. Against the mesmerising terrain of Greece, Takahashi has declared a topos of the body and all that it has lived through, lending it an immortal thought. In reimagining the body as landscape, there can be no ending—only a view of what comes, and a patience for change.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, translator, and editor. Born in China and living on Vancouver Island. then telling be the antidote won the Tupelo Press Berkshire Prize and will be published in 2023. How Often I Have Chosen Love won the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize and was published in 2019. shellyshan.com

*****

Read more on the Aysmptote blog: