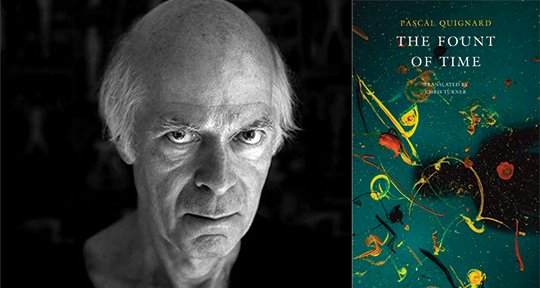

The Fount of Time by Pascal Quignard, translated from the French by Chris Turner, Seagull Books, 2022

You might not know it, but you’ve likely been affected by the work of Akiyoshi Kitaoka, a professor of psychology and specialist in visual perception. That is—if a static image has ever given you vertigo, if you’ve taken LSD at some point in your life, or if you happen to be a fan of experimental pop band Animal Collective, whose 2002 album, Merriweather Post Pavilion, is outfitted in one of the scientist’s undulating patterns. Carefully constructed to delude the eye, Kitaoka’s psychedelic, shifty images induce an anomalous motion illusion, wherein selective shadings and geometries, coupled with repetition, tricks neurons into thinking that a picture is moving when it’s not. What results is an extremely convincing array of stillnesses that nevertheless quiver, spin, and oscillate. It’s only a tiny, easily recognisable fissure in the reliability of perception, but just as such illusions hint towards the limits of seeing, the indisputable evidence of our deceptive and limiting physicality sends us outward, pushing us towards all that exists in the unseen—that which finds its way to us through the intuited at, the briefly sensed, the deeply felt.

Pascal Quignard is restless with the unseen. His immense body of work—comprising of over sixty titles—plunges into the lush fabric of invisible things. From loss, to silence, to love, Quignard introduces the solid infrastructures that seem to contain these wild and eternal subjects, only to then elaborate upon their perceptible dimensions with the secret experience of echoes, phantoms, and the vivid reality of the imagined. From novels that wrestle with the psychological tortured voyeur (Villa Amalia) to ekphrastic writings on sexual imagery, the author is famed for his ability to excavate the torrid undercurrents of our daily existence—the metaphors, symbols, and myths that enrich and multiply human experience.

The latest work to make its way to English, The Fount of Time, is part of Quignard’s Last Kingdom (Dernier Royaume) series, which today comprises of eleven titles perhaps most notable for their resistance to classification. At once novelistic, aphoristic, philosophical, and poetic, the books flow through the author’s intelligence and preoccupations, traversing the topography of his mind in the rhythm of thinking—which is to say, formlessly. The Fount of Time joins three other Last Kingdom books in the Anglosphere, all in the fastidious and graceful language of Chris Turner, including: The Silent Crossing in 2013, Abysses in 2015, The Roving Shadows (which won the 2002 Goncourt) in 2019—with Dying of Thinking due out in early 2024. All of the titles hold to the same mutable nature, composed of chapters of widely varying lengths (some a dozen pages long, some containing only a sentence). Of the sections, there are ones that sound like the beginnings of stories, and ones that sound like endings; the contents verge from the studious and cerebral, to the simplicity of oral lyricism. Subjects include the colour red, the spring, classifications of matter, civil war, seclusion, The Huainanzi, animality, orgasms, fairies, ancient Rome, and happiness. The prose is passionate, distant, and indelible. Certain lines are almost even funny. It makes sense that Quignard has now dedicated himself to this series; it is essentially to state that after a lifetime spent pursuing a craft bound by definitions, delineations, and elucidations, he has forsaken clarity for the infinitely more true nature of life’s complexity. The cage door of literature’s maniacal self-diagnosis is flung open; the words have been freed.

As such, the reviewer’s task in approaching these works is uncertain and—one could argue—unnecessary. How is one meant to describe, analyse, or even appraise a book that can hardly be contained within its covers, that create not a linear progression but an ever-expansive web, that takes place in the negative spaces? It seems hardly impactful to say that this is a treatise of time, of ardor, of death—what literature isn’t? In truth, such texts take the critic’s role to task, for it casts the reader in the role of co-conspirator; it is only the act of reading the unites these disparate elements. It is the reader’s mind that must knit and weave together the pedestrian and the profound, the ancient and the contemporary, the incidents and the ideas. In this, Quignard invites us into thinking alongside him, into an active engagement between two consciousnesses. Reading, he reminds us, is the essential counterpart to the sole, searching, finite eye of the writer—the truly delimited action that reaches everything, collates everything, and even understands.

Despite eluding the diagrammatic, however, there is a certain continental plate, cohering the text, that distinguishes the prose from chaos. Throughout The Fount of Time and all of the Last Kingdom, what surfaces is the persistence of what Quignard calls the “Erstwhile”—the continual and concurrent time instilled within the present. One might call it the eternal now. Distinguishing the Erstwhile from the past, the author asserts that while the past is always fragmented, subject to memory, interpretation, and record-keeping, the Erstwhile is whole, foundational, and perpetual: “That’s what determines the past by contrast with the Erstwhile. We change our past whereas we do not change our Erstwhile. Behind the century, the nation, the community, the family, morphology and chance, that which conditions goes on endlessly conditioning. Matter, sky, earth and life go on constituting us and do not perish.” There’s a certain mysticism in this regard of time, with its daunting evocation of the everlasting; Quignard, however, is using the language of spirituality to qualify a secular phenomenology. It is not a divine presence that occupies the other realms; it is our own world, our own histories, and our own psyches. And in approaching this subterranean maelstrom, what feels like a revelational spiritual experience is in fact the sensation of art-making. Of dreaming, imagining, and writing. “Language,” he tells us, “is the house for all that is no more.”

Have you ever seen the face of a dead loved one flash across a stranger’s? Have you ever sensed, upon coming somewhere new, that you had been there before? Have you ever faced the sea and felt it untouched by time? Have you ever read a piece of music and played it in your mind? Have you known your lineage? Have you adopted memories that aren’t your own?

That is the work of the Erstwhile.

In The World of Silence, Max Picard notes that: “It is language and not silence that makes man truly human. The word has supremacy over silence. But language becomes emaciated when it loses its connection with silence. Our task, therefore, is to uncover the world of silence so obscured today—not for the sake of silence but for the sake of language.” The Fount of Time exemplifies this urgency, this responsibility of literature. Because Quignard is a champion of the word, because he vividly senses the unspoken and the immaterial, he has heard the call to write his way towards it. It is language that makes up the surface, and it is also language that sinks hooks deep into the water to drag up what can be thought. Though it is but a mirror-system of abstractions and representations, language is the only way we can walk upon silence—the only way we can articulate the Erstwhile. In chapter five, Quignard tells the story of a man whose brother has died. The man says: “We go to where what is lost draws us. We rush there. Every woman and every man rush to where they lost themselves.” In chapter twenty-three, he tells us: “The missing image is always there first.” In chapter thirty-two, he relates the words of Emperor Claudius: “The emperor, a great enthusiast for the Etruscan world, is urging that we look to the most ancient for the newness of that time when the brand-new existed in a free state.”

Here is the line that the reader can draw: the writer is pulled to what has been lost—to the missing image. And to write the missing image, one has to imagine oneself there. When it existed in a free state. There is so much corruptive distance between here and the “newness,” but Quignard upholds that if we persist in our dialogue with artifacts, with the thinkers of antiquity, and with the way language holds its own origins, we can grab hold of the lost thing that has been, all along, travelling alongside us.

The way that Quignard writes would be unforgivable had it not come from an author who has already proved himself formidable. For what one seeks, in literature, is to attach oneself to a fiercely original, incomparable intellect, to be shown something new, to find the world wider and more various than what was previously known. We probe at the borders of the Erstwhile in our own, discrete ways, but to comprehend its immensity, we require the help of fellow seekers. In this way, The Fount of Time is a gift—not only because is full of wisdoms, eccentricities, and curiosities, and not only because it does the magic work of evoking timelessness, but because it manifests dozens of interventions and entrances into the terrain of human experience. Because at any time, you can encounter a sentence that incites you to close the book, sit back, and—in Quignard’s brilliant company—think.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet. How Often I Have Chosen Love was published in 2019. Then Telling Be the Antidote will be published in 2023. shellyshan.com

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: