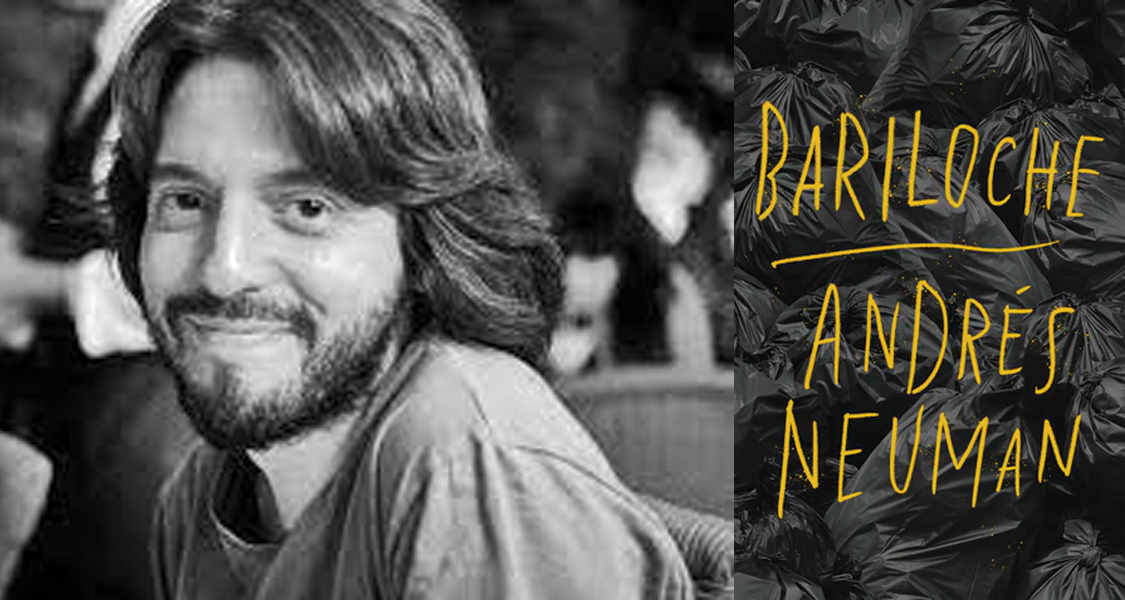

Bariloche by Andrés Neuman, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers, Open Letter, 2023

Andrés Neuman’s first novel, originally published in 1999, is his fourth to be translated into English—following Traveller of the Century, Talking to Ourselves, and Fracture. Any thoughts of difficulty or inadequacy suggested by this twenty-odd-year delay can be quickly dismissed: it is worth the wait. Finalist in the Herralde Prize, and described by Bolaño as containing something “that can be found only in great literature, the kind written by real poets,” this story of a trash collector living in Buenos Aires who obsessively compiles puzzles depicting the region of his childhood—the Bariloche of the title—is densely powerful.

The narrative follows Demetrio as he goes about his job collecting trash with his co-worker, El Negro. They work while the city (or most of it) sleeps, stopping only to breakfast on cafe con leche and medialunas, occasionally inviting a homeless person to join them. Their dialogue is simple, and El Negro talks far more than Demetrio, who is absorbed in thought—or in nothingness, El Negro can’t tell. After work, in the early afternoon, Demetrio returns home, where he collapses into bed, finding a kind of brief relief there:

He went to the bathroom, pissed with relish, took off his shoes, stroked his pillow, breathed between the sheets, the sheets were dissolving into something else becoming water, becoming waves.

The evening before his next shift, Demetrio works on puzzles, always of a scene of Nahuel Huapi, near Bariloche: mountains, water, sky, a cabin. As he sorts through the pieces, he recalls a teenage relationship with a redheaded girl that ended when his father grounded him, and from which he has never recovered.

Sometimes he wonders if there couldn’t be, in some secluded corner of the landscape behind the amancay, perhaps, perched on a boulder by the shore, a haunting figure, pale-faced in the shadows, reddish tresses rippling till the wind sweeps her away: those copper threads he had desired, touched, and smelled one frozen dusk.

Sentences sing out in Myers’ translation. We have the perfect rise and fall of, “To the window came the undulating supplication of a meow,” with the inversion of an opening prepositional phrase, the repeated assonance and the matching syllable stress of “undulating supplication,” as well as the beautifully arresting, “Her stockings curled into themselves like black cream”; it is impossible to not visualise this happening as you read.

It is not always so fluid—frequently, it is the odd little moments that resonate, provoking a sharp dissonance that stops the reader in their tracks. There is a precision in this craft too, in which unusual linguistic choices and constructions throw particular words into relief, deliciously wrong-footing the reader and demanding they stop and pay closer attention to the meaning. What does that word, that I might use every day without thought, really mean? So we have, “The light churned relentlessly on the lake”—how?—and “he registered the obese impact of consciousness,” along with an “anarchic sun” and a “premature lunch.”

In Demetrio’s exhausting role as a trash collector, physical sensations take centre stage. Touch, tiredness, hunger, bodily needs—these are all described in minute, precise detail: “Exhausted, full of miniscule tremors rising into his muscles,” or “At the sight of the faint warm stream, he was pierced by a distant sense of guilt.” Above other physical needs, hunger and tiredness take up Demetrio’s time. An early clue can be found in Neuman’s choice of epigraph for Bariloche: “It is thus the fatigued survive.” The author has explained that he first dreamt up the novel in reading an essay by John Berger (from which the epigraph is taken), which argues that exploited workers rarely notice their own exploitation because, worn out and famished at the end of a working day, a brief, duplicitous sense of wellbeing can be found in a meal and a rest.

With this comes apathy and a kind of numb detachment, echoed in the descriptions of Demetrio’s surroundings—“the absent neon of shuttered storefronts.” Even an affair with his co-worker’s wife is relatively emotionless. In contrast, Neuman paints an astonishing picture of the endless, fetid waste Demetrio deals with:

He imagined that the mass, once it had digested its putrid daily feast, would excrete the leftovers toward the heart of the city, where they would disperse and make their way into every home, and into those containers on the street that would later feed the dump once more, and so on, over and over again.

The waste itself at times takes on human characteristics: a garbage truck become animate; garbage bags grow human-like. Its corporeality overwhelms, and marks a stark distinction from Demetrio’s apathy.

Instead, life and feeling for Demetrio is achieved through puzzles. Doing jigsaws represents a way of sorting through his memories, of briefly regaining a sense of self, and momentarily experiencing the lost arcadia of his youth. Recollections of his relationship are tender, sweet and vibrant; his “whole life has been sort of begging for scraps of that feeling ever since.” In these short sections, heady naturalistic writing bursts out, often in first person.

It is in these sections, too, that the reader begins to note the structural complexity of Bariloche. The book begins with what seems to be a fairly typical linear structure and third-person narrative voice, but this is suddenly interrupted by an ‘I’ recalling the past—Demetrio, and then another beckoning from the future—El Negro. Chapters sometimes alternate between Demetrio in the past and Demetrio in the present, while parentheses often encase fragments of Demetrio’s memories within the main present-day story. Tracing the shape of a mountain, the narrative rises to a peak in the middle section—in which the chapters describing his relationship with the redheaded girl are juxtaposed with those describing his present-day affair with Veronica—before it breaks like a wave: his father ‘waiting, standing in the doorway, a long stick in his hand.’ Then, after months of being grounded, teenage Demetrio surrenders to insomnia and five-hundred-piece puzzles. As the metronome ticks faster and faster between past and present, the narrative grows feverish, rushing, increasingly fragmentary. The effect is kaleidoscopic and dizzying.

The pieces of Demetrio’s puzzle jostle for position, and the reader must piece them together themselves. Boundaries, which are already weak lines through which senses easily slip (exemplified by Demetrio’s “drowsiness smeared the pavement”) disintegrate entirely, until Demetrio’s past and present begin to interact at his living room table:

And there, at last, aflutter, is the scarlet spectre of a haunting figure in a nightgown, her tempered pinecone breasts, an apparition floating past the windowpane, who contemplates, with eyes transparent as a baffled fish, the back and shoulders of the man, who hunches there in solitary labor at the living room table

Finally, the narrative frenzied: “a bolt of lightning cracked across his timeline.”

Neuman is interested in exploring borderlands: the rubbish collector who grew up in nature, surrounded by urban waste, unseen by the rest of the population, operating in the dark of early morning, existing at the borders of society. In one scene, Demetrio pieces together a broken dish from a rubbish bag—save for one piece. He leaves it on the pavement, an offering. (To who?) The trash heap he and El Negro feed daily becomes its own puzzle: “He stared out at the crazed mosaic, transfixed by its exhausted colours.” In laying out a narrative table of puzzle pieces for the reader to fit together, he invites the reader to feel the strange edges of Demetrio’s life.

Bariloche is bleakly luminous and fascinatingly fractured. “Luminous” could well be applied to Robin Myers’ translation, too, along with a barrowload of epithets: brilliant, inventive, masterly. But what do we mean when we call a translation any of these? More often than not, a reviewer or reader cannot read the original to make an assessment of the translation’s so-called faithfulness. Instead, we are acknowledging that the writing in English has an affect on us: the choice of this word, then the next, and the next, until a whole is formed, and that a translator-as-writer who has produced this effect. While reading Bariloche, I often found myself thinking of Kate Briggs’ This Little Art, in which she argues Barthes’ notion of writing as “a kind of catch or halt or temporary immobilization in the run of culture” can be applied to the translator, who presses her finger “down on the run on alternatives” and “makes it stop.” Together, Neuman and Myers have made it stop, just as Bolaño said, in “great literature, the kind written by real poets.”

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: