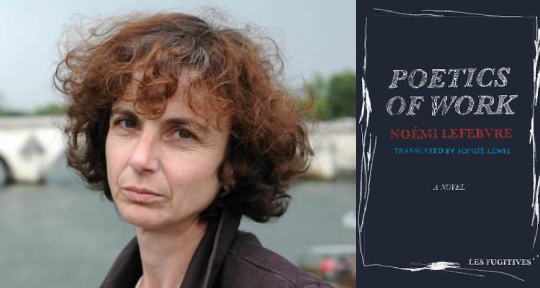

Poetics of Work by Noémi Lefebvre, translated from the French by Sophie Lewis, Les Fugitives, 2021

The deluge of our paroxysmal century has initiated a current in public intellectualism: a (only negligibly desperate) return to the texts that had attempted to reconstruct human thought and society in the aftermath of WWII, the total fracturing of order having led to a global crisis of aimlessness. I too, like many others, found myself, in the last year, grabbing my copy of The Origins of Totalitarianism in search of some clarity: “There are, to be sure, few guides left through the labyrinth of inarticulate facts if opinions are discarded and tradition is no longer accepted as unquestionable.” Though one wants to resist the striking relevancy of Arendt’s preface to the 1950s edition—“It is as though mankind has divided itself between those who believed in human omnipotence . . . and those for whom powerlessness has become the major experience of their lives”—it befits to understand its sustaining fact: our past is with us. Miles won by the powers of a corrupt engine are not achievements, but illusory, precarious compromises.

In Noémi Lefebvre’s Poetics of Work, the narrator is similarly attempting to decode the estranged world with resilient methods—reading (and re-reading) Klemperer’s The Language of the Third Reich, ingesting an extraordinary number of bananas, smoking what appears to be an unlimited supply of weed. Lyon, the city trembling in the background, is both a container and a newly unbreachable concept, reconstituting after waves of unrest caused by a proposed workers’ rights reform bill. There is a “strange new climate” that clots the senses, and one is struck, at the very beginning lines, by the great distances at the intersection between the private and the public. That we are trapped in our regarding, our helpless understandings, and the world, irreverent and oblivious, goes on anyway.

Poetics of Work wears its designation of “novel” like an alibi. It is not a story of a person, a place, or a time, and is entirely unconcerned with reality as a thing to be adopted or adapted. Instead, it is a radical assertion of the mind’s omnipresence, at once myriad and intact, the only entity capable of reconciling impossibilities—the physical with the abstract, the immense and the intimate, the existent and their ghosts in memory—by strange, incredulous methods of inquiry. By thinking. It is a transcript of the transcendental geometries created by thinking, as it flows and elevates, creating depths, creating beyond limits.

It is also, of course, an acknowledgement of the world going on, anyway.

Noémi Lefebvre is a writer that evokes sonority. Similar to her English-language debut, Blue Self-Portrait, which conversates with the soundscape of Arnold Schoenberg, Poetics of Work has a formal sequence, reminiscent of a master pianist at dialogue with her instrument. The sentences run long in soliloquy-arpeggios of observations, considerations, and wonderings. Certain lines and words appear and reappear throughout the text in percussive periodicity. The words simmer and boil and rest again, speaking to that significant aspiration of verse—a replete symbiosis between form and function. Sophie Lewis has gently dislodged this kinetic, dynamic text from its original French and it runs, unfettered, in its English rendition. A translation must always maintain the energy of its original to become a reverberation equally melodic, and here, the continuance of Lefebvre’s principle musicality ensures that this work is not an echo, but a profound resonance.

The text finds its skeleton in imaginary dialogues and encounters with a superego named “Papa,” amalgamated from the various authorities of success-by-definition: upper-echelon lifestyle habits (“dug his heels into the flanks of his all-terrain purebreed”), markers of cultivated intelligence (“alternating Plato and 4×4 everyday”), advanced skillsets (“coding the results of sequencing the genome”), and still enough conscientiousness to claim an effectively irritating moral superiority (“giving his universal blood”). This heinous character presents the perfect foil for our narrator, who (unnamed, ungendered) is implicated in-between the necessity of employment, the moral incomprehensibility of labour in capitalism, and the volatile conviction that there is still some place, amidst and despite all of this, for poetry.

‘Don’t you think it’s rather bad taste to talk about poetry at this particular juncture?’

‘Yes, Papa.’

‘Aren’t there more urgent problems?’

‘There are, Papa.’

Poets are always finding themselves in the impassioned position of advocating for their craft—emphasising its vitality and relevancy, redefining its formations and appearances to befit the contemporary, deploring its indolent lack of popular appeal, and, in the way of Poetics of Work, establishing it on the hierarchy of labour. The devotion to poetics is not unlike a religious fanaticism; there is the very same appellation of titanic importance, of elevating its symbolic laws to the laws of nature itself, of connecting its very practice to the actualisation of the human soul. When I was younger and more excessive, I would exert my defiance and defence of poetics in even the most unwelcomed and inconsequential of places—the customs counter. They would ask, “What do you do?”, upon which I would answer, with what I imagined to be “moxie”: “I’m a poet.” The agent, routinely unamused, would then say something along the lines of, “That’s a job?” Huffily, I’d say, “It’s not a job. It’s a vocation.” As such I found myself often shuffled into the eighth circle of customs-hell, sunken into its underbelly as gloved hands unpoetically swabbed all my belongings for narcotics.

. . . if I preferred to hang on to my vague and completely unfounded sense of a poetry deficit, if I preferred to fixate on a romantic and outmoded notion of this useless and entirely futureless non-profession, it was because I myself was, as I should one of these days admit, a shiftless loser too, wasn’t I?

The straightforward identification would be, yes. To even have the privilege of avoiding employment, and then spending most of that time smoking pot and wondering about why one has to “work,” perhaps already denigrates the subject to the traditional definition of “shiftless loser,” and the narrator spends the duration of the text adhering to the descriptor of “shiftless” while somewhat refuting, by the equations of thinking, the pointed “loser.” Poetics of Work is, essentially, a dictum of the employment-seeking paradigm under the bipolarity of work, how it somehow indicates towards a pursuit that elaborates existence with the complexity of purpose, while also having become something that relegates purpose to an afterthought, left for contemplation at one’s own leisure, off the clock, after having done a hard day’s . . . work.

Of course poets are so ardent, because its whole purport is that the human imagination is ultimately a force that shapes the world—a creative, birthing force, capable of great radiancy and horrors—and the conduit we have for it is language. A knowing ownership of poetic language is the translation of ideas to actualities, a phenomenological investigation, our primary defense against the simplification and hardening of things. It is what we have as adequate to understand, feel, and pass on those spare elapses of awe, or beauty: the childhood rhythm of corridors, the human figures of evening light, the conjuring of an ocean in a seashell.

Yet the redundancy of this whole affair rises to the surface when, as the narrator says:

When you see someone, a black guy, did I need to say it, getting punched in the chest by a cop with the full weight of his fist and his impunity, then being dragged away by another who kicks him to a pulp on the riverbank pavement, you realise that all you’ve been able to write in your gilded youth is pure crap.

The painful irony of poetry is that the craft of looking deeply at things inevitably leads to an agony of suspicion, that art—in practice a facilitation of moral aspirations and societal progress—fundamentally cannot equate to action. Poetry’s value, though marginalised, is not actually undermined; even those apathetic or disinterested in reading or writing poems can still appreciate, when pressed, the sublime and necessary function of poetics in everyday life. So it is that poets proclaim the necessity of their work not necessarily to the anonymous public at large, but to themselves, to fellow poets. To interrogate that uncertain, median space all principled writers must navigate, between poets as Shelley’s “unacknowledged legislators of the world,” and poetry itself as insular and complicit in the privilege of cultural nearsightedness. Truth is strangled out of ego; the poet seeks first to know themselves, then second to justify the being of themselves.

But suppose the question is not—is poetry doing enough? What if we were to ask instead: can we imagine a world in which we no longer doubt that poetry—its demand for precision and clarity in matters of the mind, its liberal insistence on the coherence of purpose, intent, and action, and its unshakable faith in the capacity of human beings to be moved and elevated by the presence of profound language—has an indispensable position? What would that poetry, capable of thinking past its own limits, look like? What would that world look like?

Arendt and Klemperer were in the act of finding language that would suffice in a tired age, one that would ascertain the impetus for reconstruction, to relieve the masses who had been integrated into an all-consuming machine, bent upon domination. We regard in them now revelations that seem still-crisp, in the dawning of the similarly annihilating and suicidal conquerings of capitalism, the existential dread of a dying planet, the fixations of violence and terror—the more “urgent problems” that our imbued concept of labour serves to be a distraction from. Employment as redemption. Employment as self-worth. Work sets you free. These impenetrable axioms are what accentuate the necessity for language, a focusing language that overpowers what forced work disconnects us from—the significance of our actions, our individual capacities for thinking, and our desire for self-knowledge. When Lefebvre’s narrator works in—

And what happens if the cultivated language is made up of poisonous elements or has been made the bearer of poisons?

Klemperer’s question.

There I suppose you have one answer as to the task of the poetic language.

“I could fill today’s world with its humanitarian tragedies,” the narrator says. Poetry will not cure a cold, absolve the pains of hunger, or appease the riot police in the streets. It will not bring back those who have died unjustly, and it will not pay the bills. But as Lefebvre demonstrates in the writing of this book, these are not any of the claims, nor any of the values, of poetry. Instead, what it promises, and often delivers, is an awakening—a disturbance from the sleep that dredges one into the automatisms of mere procedure.

As another poet disguised as a novelist, James Salter, wrote: “There comes a time when you realize that everything is a dream, and only those things preserved in writing have any possibility of being real.” To say this is not to denounce the world as inconsequential, but to comprehend that its proceedings and designs are apart from us, and the way that we approach it—and affirm our control—is through the articulation of our own language.

If it is the way of the world go on anyway, let us hold on to this—our essentialities, our consciousness, the iridescence of our contrary imaginations.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor. Find her at shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: