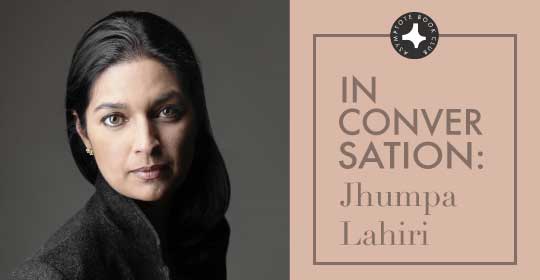

In our fourth Asymptote Book Club interview, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jhumpa Lahiri spoke with Asymptote Assistant Editor Victoria Livingstone about her translation of Domenico Starnone’s Trick.

In this discussion about her work and the forging of her own artistic identity, Lahiri reveals why translating Starnone seemed like “a sort of destiny.” Lahiri draws us into Starnone’s fictional world, but also reflects on her own mutable relationship with language and writing, and on the marvelous yet precarious ways in which our lives unfold.

Victoria Livingstone (VL): I wanted to begin by asking you what brought you to translation. I just finished reading In Other Words in which you reflect on your decision to switch from writing in English to writing in Italian. Did you see translation as a natural progression after working between multiple languages and living in Italy? And what drew you to Domenico Starnone in particular?

Jhumpa Lahiri (JL): During the initial part of my stay in Italy, I wanted to translate something, but I didn’t know what it would be. I was reading only in Italian for many years. As my reading progressed, I would think that I would like to translate this person, or that person. Once my Italian was stronger and my reading in Italian seemed to have a larger ongoing purpose and focus, translation was something that really intrigued me.

I was considering it in this vague way and then I read Lacci by Domenico [Starnone] and immediately felt that if I were to translate something, that this would be the book I wanted to translate. I felt very close to it. It spoke to me very deeply. It felt like the natural first step. That’s how it started. When he asked me to translate the book, we were already friends and I felt—I feel now—that it was a sort of destiny. Everything was properly aligned in the moment that I was drawn to the idea of translating and was ready to translate with the appropriate amount of distance. That was when Lacci, which became Ties, won a prize which enabled the translation to be funded. It was a series of fortuitous circumstances that led to the translation of that book a couple of years ago.

VL: In your book In Other Words, you describe wanting to write exclusively in Italian. You talk about Pavese in relation to translation, about the selection of words and the intimate connection to language that translation involves. Translation draws you back into the target language, in this case, into English. I wanted to ask about your approach to translating these books. Did you consult Starnone? Can you talk generally about your process as a translator?

JL: My process both times has been more or less the same. I read the book various times in Italian and tried to absorb it as best I could as a reader. Then I started to translate. With both translations that meant reading everything out loud and then translating sentence by sentence. I sit with the text, read the first sentence out loud, hear it, and then translate it into English. The process moves forward from there. I wasn’t doing that in the beginning with Ties. At first, I was translating silently, and then one day I started to read the sentences out loud and I realized it was a totally different experience for me.

VL: Reading the Italian out loud?

JL: Yes, reading every single word out loud, then pausing, and then translating it. That just gave me the rhythm and the point of entry that worked for me. Once I had a complete draft, I went through it various times on my own and then with Michael Reynolds, the editor at Europa Editions. Once I was more or less satisfied with the results in English, I read that version out loud to a friend who followed me in Italian. That was the completion of the whole journey: to read it out loud in English, shadowed by the Italian, by a reader who wasn’t me. As for Domenico, I asked him as needed, occasionally, when I wasn’t sure exactly what he meant by a particular word or passage. I sent him texts when I was here [in the U.S.]. Most of the books were translated in New York and in Princeton, so we were not in the same place. I go to Rome often, however, and when I was there, I brought him lists of this and that and we talked about it. With Trick, of course, there was the issue of the dialect, which I talk about in the introduction.

VL: Yes, I was going to ask about that.

JL: Domenico and I discussed that in person. He translated those words into Italian, gave me the gist of the content, and I had to go from there.

VL: In your translation, did you try to differentiate the tone or anything else about those sections translated from dialect from the parts of the text translated from Italian?

Lahiri: There really isn’t that much dialect in the book. There’s a scene where they go into the bar. The people in the bar are speaking in dialect, though it’s all written in Italian. We know that these secondary characters are speaking in dialect because the protagonist is reacting to this fact. It was more of a tonal consideration. There are a couple of words here and there that are abbreviated words in Italian, in the Neapolitan tendency to truncate words. I didn’t need to talk that through because the meaning was clear. It was more that there are some passages with lists of words in dialect that the character is remembering. Those were specific terms that are used to describe the character’s relationship to his past and to Naples. The dialect is representative of that place, of its culture, of the combination of intense affection and violence that the character perceives and reflects on when he goes back and is once again in that physical space. The dialect, much like the ghosts of his past, comes to the fore to haunt him. They are words that are circulating in his mental space more than anything.

VL: You mentioned that when you begin a translation you read the book a few times to get a sense of it. In your introduction to this translation, you mention reading Henry James’s “The Jolly Corner”—in Italian translation and in English. Since translation is always an interpretative act, I wonder whether your reading of James’s story influenced your approach to translating the novel?

JL: I actually didn’t turn to James’s story, which I had read long ago, until after I had translated the entire book. I waited until the appendix. I knew that the appendix was doing something very complicated and that the James story was spliced into that material. In the rest of the book the James story provides plot devices and thematic consideration, whereas in the appendix the text itself is in dialogue with James and there are pieces of James imbedded within it. The more I read James, the clearer it was what was going on, how the two works were connected.

VL: Yes, it’s a complex relationship, as you said. I think that your translator’s introduction builds another layer on that complexity. Your ideas about the act of translation leaving ghosts behind were very interesting.

I also wanted to ask about art. Trick is, of course, also about art, about the nature of creative talent, the connections between generations of artists, the sometimes random factors that shape artistic careers. Daniele [the narrator] reflects often on this. Was there a particular aspect of this book, or perhaps some passage, that made you reflect on your own career in the arts?

JL: I think that what moves me the most about this novel is the meditation on what it means to become an artist, how it happens, all of the factors that might prevent it from happening, the fighting against destiny, the fighting against what is expected of you, what bloodlines dictate, the forging of an entirely new way of being and thinking. That spoke to me, that speaks to me very deeply because I feel a lot like this character. I feel that my own life, my own path as an artist, has consisted of pushing against what was expected. This character meditates profoundly on the precarious nature of all of this, the idea that so much of it is a matter of chance, dumb luck, something goes one way as opposed to another way, and realizes that his life could have gone in so many other directions so easily. There’s just the sheer determination, the resistance, the refusal to capitulate to certain expectations in the dreamed desire to forge an identity. I find that this novel articulates that in ways that I was never able to until I read it. When I read it, I thought, yes, this is exactly how it feels in some sense, looking back. I’m not as old as the narrator of Trick, but I feel that I’m old enough to look back on my life and to think and to marvel, and also be terrified by the randomness of it all.

VL: Towards the end, Daniele says that “variability is hard to draw.” In your introduction, you discuss the ways in which you had to “discard numerous possibilities” in order to translate the book. Do you see any other parallels between Daniele’s effort to illustrate “The Jolly Corner” and your process as a translator?

JL: I think it’s getting at the same idea. In the end, in order to get anything done in life, one has to choose. And choosing involves discarding multiple possibilities. I think that the novel takes this metaphor and unpacks it and layers it in a very subtle way. It deals with what it means to choose an identity for oneself and what it means to choose one illustration as opposed to another for a given story, as is the task of this illustrator [the narrator in Trick]. That is also the translator’s task, to choose one version of multiple possibilities. That has become clear to me even in my brief experience as a translator. For any one adjective I choose, there can be so many others. When it comes to structuring sentences, there are so many reasonable permutations. In that sense, translation is, of course, an act of interpretation. When I choose to put down words in a translation, I am well aware that were I to have translated it a year before or two years later, the result would be different. Another very interesting element of this book is evolution and how we are produced. If one has children, whether two or four or ten, there are all these other versions that never get born. I think that the book is looking at that idea as well. Why are we the way we are? Why are our children the way they are? Why are our siblings the way they are? Why is mankind shaped in this particular way? There’s all of this very interesting biological, evolutionary chain language in this book, and in Ties.

VL: Thinking of these meditations on biology, there are some reflections in the book on the nature of creative talent. The narrator describes a tension with a sort of raw, artistic drive. During the course of his career, he seems to be trying to control it, to refine it into something.

JL: The book is playing with a series of opposite tensions. In terms of this character, he draws a clear contrast between the passive kid, who is very… the word in Italian is umbratile, which describes a person who is not very center-stage, someone who’s a bit moody, a bit in the corner, lurking, with a kind of shadowy sensibility. I translated it in an unconventional way. It was a struggle for me to figure out exactly how to put it. In the end I wrote “in the woodwork” as a version of that sensibility, that posture that certain people have, of being timid, of not wanting to draw attention to oneself, which is often the case for creative people. And yet the creative act is so bold and so audacious. To be an artist requires you to take that tendency to be in the woodwork and to watch, to not participate, to quietly observe life, and to take that energy and that sensibility and convert it into a very active stance. I found this protagonist very convincing in terms of looking at the inherent contradiction in so many artists I know. Speaking for myself, absolutely I carry within myself this contradiction. I always have.

VL: I’ve been thinking too of the relationship between your work as a writer and your work as a translator. You’ve talked about the ways in which writing in Italian has opened new possibilities. I wonder if your experience translating has influenced your writing. A literary scholar and translator, Roger Shattuck, talked about translation as a process capable of “reshaping and enlarging English in order to reach meanings with which it has not yet had to grapple,” a way of expanding the language. I wonder if translating from Italian, in addition to writing in Italian, has expanded your repertoire as a writer.

JL: I knew Roger Shattuck. He was a wonderful soul. Even back then, in Boston, I was surrounded by people who took translation very seriously. He was one of them. It got me to think differently about the whole literary project. But, yes, I hope so. I can say that the writing I’m doing in Italian is different from what I’m doing in English and from what I might have done in English. It’s widening something for me. It’s a form of growth. Domenico has been very helpful with the work that I’m producing in Italian now. He has been reading what I’m doing. There’s a very fertile back and forth in terms of my being his translator and he a reader of the work I’m producing in Italian.

VL: Do you have any future translation projects?

JL: The immediate future is a Penguin Classics book of Italian short stories which I’m editing and putting together. That’s been an ongoing project for two years. It involves forty short stories in Italian, most of them from the twentieth century. More than half of the authors have never been translated into English before. It’s a very exciting project. We have a team of six different translators, including myself. That is finally taking shape and should be out in a year. It has been a real learning experience for me, shaping this volume. That’s the immediate translation project. After that, I don’t know. I have a few authors from that volume that I might want to translate more of, but I haven’t decided yet. I’ve just written a new novel in Italian and so my energy will go towards translating that myself.

VL: Ann Goldstein translated the first novel you wrote in Italian?

JL: She did. That was then, and now I feel that I’m in a different place. I recently translated one of my short stories into English, which appeared in The New Yorker a couple of months ago. I now have more of a sense of what it will involve to translate myself. But we’ll see. That was a very short story that I had written four years ago in Italian. It was ten pages long. Translating it into English was weird, but it was also brief. I don’t know what it will be like to translate a novel, but I feel that it’s important to try. If it doesn’t feel satisfying, I may have to reconsider the choice. Right now every project I’m doing has its own set of needs and I can’t really say until I’m inside of it how I feel about it.

I will just add that I recently gave a talk on a writer named Leonora Carrington, who is fascinating because she wrote in two different languages that weren’t “her own,” weren’t languages she had grown up with. She was from an aristocratic family in England and then ended up living in Mexico City for seventy years. She wrote in French and in Spanish. Some of her French writing was the result of dictation, which I find really fascinating. She was a powerful woman who had a completely different frame of reference in every sense. She also did not translate herself. Her writing in French and in Spanish was translated into English by other people. I find her a fascinating case and, in some sense, a new guiding light for me given the strange things I’ve been trying to do. I am realizing that there have been other people who have tried to explore new linguistic identities as writers. It’s been really fascinating to think about her and her very creative journey. In any case, she’s someone I’ve been thinking about a lot.

Photo credit to Marco Delogu

Jhumpa Lahiri is the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Interpreter of Maladies. Her books include The Namesake, Unaccustomed Earth, The Lowland, and, most recently, In Other Words, an exploration of language and identity.

Victoria Livingstone is an assistant editor at Asymptote. She holds a doctorate in Hispanic literature and teaches Spanish at Moravian College. She researches translation history and translates literature from Spanish and from Brazilian Portuguese. Her first book translation was Song from the Underworld (Achiote Press 2014), a book of contemporary Maya poetry by Guatemalan author Pablo Garcia. She also writes frequently on social issues and contributes to a number of publications as a freelance writer.

If you’d like to read our next monthly selection, head to our Book Club page for more information. If you’re already a subscriber, why not join the conversation on our online discussion group? To get you started, here’s Asymptote Assistant Editor Victoria Livingstone’s take on the novel…

*****

Read more Asymptote Book Club interviews here:

- Asymptote Book Club: In Conversation with Martin Aitken

- Announcing our February Book Club selection: Love by Hanne Ørstavik

- Asymptote Book Club: In Conversation with Rimli Bhattacharya