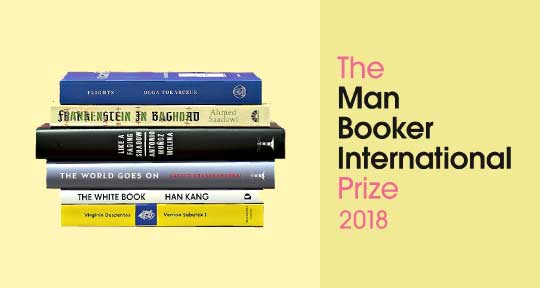

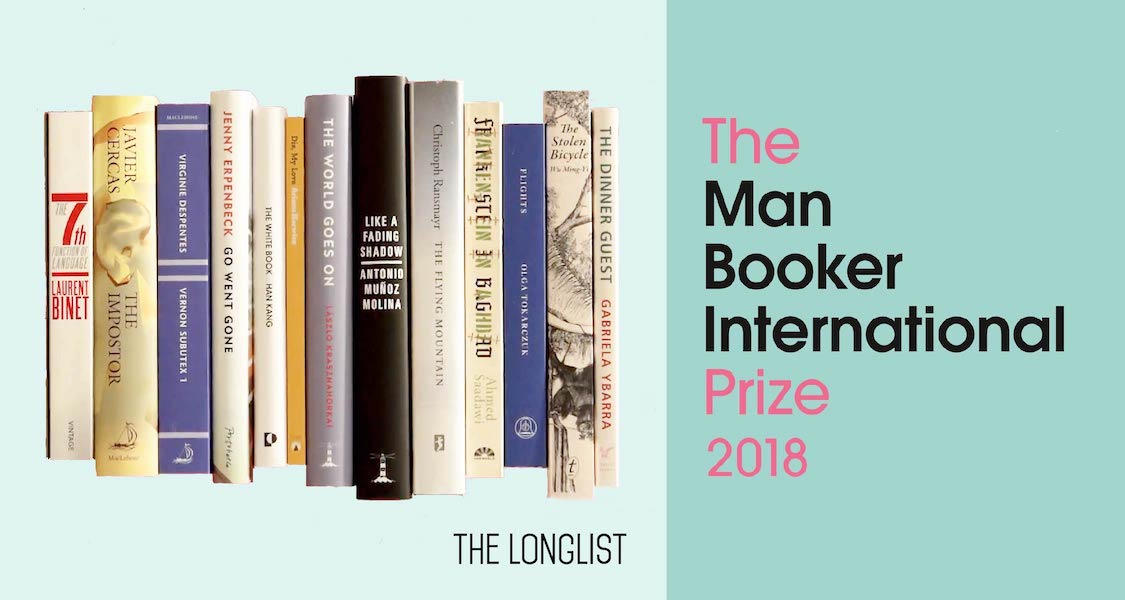

“A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a re-reader,” Vladimir Nabokov reminds us in his article “Good Readers and Good Writers”. There are so many books in this world, and unless your life revolves solely around books, it might be hard to be widely read and an active re-reader. Attaining this level of perfection that Nabokov describes is impossible, but the idea of re-reading as a tool to better understanding the value of a book underpins the philosophy of the Man Booker Prize International’s judging panel since its inception.

Place: Poland

Announcing the Winter 2018 Issue of Asymptote

Celebrate our 7th anniversary with this new issue, gathering never-before-published work from 30 countries!

We interrupt our regular programming to announce the launch of Asymptote‘s Winter 2018 issue! Here’s a tour of some of the outstanding new work from 30 different countries, which we’ve gathered under the theme of “A Different Light”:

In “Aeschylus, the Lost,” Albania’s Ismail Kadare imagines a “murky light” filtering through oiled window paper in the ancient workroom of the father of Greek tragedy. A conversation with acclaimed translator Daniel Mendelsohn reveals the “Homeric funneling” behind his latest memoir. Polish author Marta Zelwan headlines our Microfiction Special Feature, where meaning gleams through the veil of allegory. Light glows ever brighter in poet Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine’s “syntactically frenetic” “Arachnid Sun”; and in Erika Kobayashi’s fiction, nuclear devastation blazes from Hiroshima to Fukushima.

The light around us is sometimes blinding, sometimes dim, “like a dream glimpsed through a glass that’s too thick,” as Argentine writer Roberto Arlt puts it, channeling Paul to the Corinthians in The Manufacturer of Ghosts. Something dreamlike indeed shines in César Moro’s Equestrian Turtle, where “the dawn emerges from your lips,” and, as if in echo, Mexican writer Hubert Matiúwàa prophecies for his people’s children “a house made of dawn.” With Matiúwàa’s Mè’phàà and our first works from Amharic and Montenegrin, we’ve now published translations from exactly 100 languages!

We hope you enjoy reading this milestone issue as much as everyone at Asymptote enjoyed putting it together. If you want to see us carry on for years to come, consider becoming a masthead member or a sustaining member today. Spread the word far and wide!

*****

Read More News:

Translation Tuesday: “I’m Scared of Those Dots” by Mirka Szychowiak

Somebody said that the healthiest ones die most easily.

Today’s Translation Tuesday comes from the Polish writer Mirka Szychowiak. “I’m Scared of Those Dots” is a haunting ellipsis of a story, concealing just as much as it reveals.

I came earlier today, let’s spend as much time together as we can, let’s enjoy each other’s company, stock up on it. As usual, we won’t be able to answer the same questions, but they will be asked nonetheless.

Zbyszek, who pushed you out of that dirty train? Your bloody blonde mop on the tracks, it still hurts. Who did it to us? How are you, Basia, do tell. What’s up? You were the fastest among us, made us so proud. Somebody said that the healthiest ones die most easily. You didn’t want to be an exception, did you? You passed away at a faster pace than when you broke the 100-metre record. Rysiu, your last letter made us angry. You better all come, you wrote. Your life with us was filled with laughter, but you were alone when you shot yourself for some strange girl. We were furious, but almost all of us did come. Almost, because Bolek had left by then, as was his custom, quietly. He fell over and that was it. Two hours after his death, he became a father. Both prematurely. Youth gave us no guarantees, we understood it early on and only Adam didn’t get it in time—it was the youth, which tore his heart apart, like a bullet. It was so literal it stripped him of all romanticism. It poured out of him, ripped him inside and that was it. Later it was Bożenka and Janusz. The two of them and the carbon monoxide from the stove. A potted fern—a nameday present—withered and then somebody called to say that there were less of us yet again.

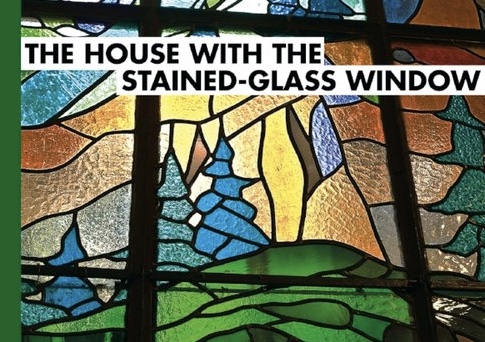

On Żanna Słoniowska’s The House with the Stained Glass Window

A strikingly crafted window into how our lives are a mosaic of the things that happened before us.

Translated from the Polish by Antonia Lloyd-Jones. London, England: MacLehose Press, 2017. 240 pages. £12.99.

Toward the middle of The House with the Stained Glass Window, the Ukrainian-Polish writer Żanna Słoniowska’s debut novel, the unnamed narrator tells us that her great-grandmother occasionally falls into fits of hysterical sobbing, which her grandmother explains as having to do with “the past.” “I imagined ‘the past’ as an uncontrolled intermittent blubbering,” the narrator says. This definition is not a far cry from the idea of the past portrayed in The House with the Stained Glass Window: not blubbering, but certainly not controlled by human forces, intermittently entering the present day until it infiltrates it, saturates it, and finally becomes indistinguishable from it.

The novel centers around four generations of women who live under the same roof in Lviv, in a house noted for its enormous stained glass window. The window sets the present-day plot in motion: it is because of the window that the novel’s narrator, who we only know as Marianna’s daughter, meets Mykola, her mother’s former lover, and begins an affair with him herself. A relationship like that would provide enough internal and external conflict to fill a novel to its brim, but Słoniowska does not dedicate much page space to it. Instead, if anything, the affair serves as a springboard to the past, to exploring the irresistible pull of it.

Rape à la Polonaise, or Whose Side Are You on, Maria?

"A hundred thousand furious women wearing black, armed with symbolic umbrellas. One hundred thousand women, undeterred by pouring rain."

A year ago in 2016, thousands of Polish women went on strike from work, dressed in all black and marched on the streets waving black flags and umbrellas to protest a proposal that would make abortion completely inaccessible to them. While they succeeded, Poland still has one of the most restrictive abortion laws in Europe. On the anniversary of the Black Protests this Tuesday, on Oct 3, 2017, Polish women marched again to demand greater reproductive freedom. Feminist writer and columnist Grażyna Plebanek recaps for Asymptote the year of struggle for Polish women’s rights and the role of literature in the protests. —Julia Sherwood

A year ago we women went out into the streets together—young and old, teenagers, mothers, grandmothers. Women from all walks of life. Women from small towns and big cities, educated and uneducated. When I first canvassed women in a Polish shop in Brussels to take part in the Black March last October, I was worried that the shop assistants and shoppers might respond in the time-honoured way: “I’m not interested in politics” or “I’ll leave it to the politicians.” Or the excuse that’s really hard to argue with: “I’ve got enough on my plate already.”

As it turned out, this is an issue that concerns us all: the issue of our freedom and dignity. In October 2016, every one of us in that shop—customers and shop assistants—poured out our grief over what “they” were planning to do to us, by introducing a near-total ban on abortion, making what is already one of the most restrictive anti-abortion laws in Europe even stricter. The following day we marched shoulder to shoulder, united by a real threat—that of being robbed of the basic right over our own bodies. We were being dragged back to the status of women during the Napoleonic times. We would no longer be equal to men and have our lives directed by others, as if we were children.

We went out into the streets in Poland, in Brussels, Berlin, London, Stockholm, New York, and many other cities across the world. In Poland one hundred thousand women joined the protest. A hundred thousand furious women wearing black, armed with symbolic umbrellas. One hundred thousand women, undeterred by pouring rain.

Sea of umbrellas. Warsaw, 3 October 2016. Photo © Tytus Duchnowski

The protests worked but in late August, almost a year later, Polish women once again went out into the streets of Łódź. Again, we wore black. However, this was a smaller and quieter march, an expression of grief. We were grieving for a young woman held captive for ten days by two men who had tortured and raped her. She ran away but later died in hospital. Her injuries were so severe that the doctors couldn’t save her.

What has happened in Poland between the two black marches—between the protests of 2016 and the funeral procession of 2017? READ MORE…

The Good Bad Translator: Celina Wieniewska And Her Bruno Schulz

"Wieniewska was correct in her intuition about ‘how much Schulz' the reader was prepared to handle."

Bruno Schulz (1892-1942) is one of the relatively few Polish authors of fiction who enjoy international recognition. Originally published in the 1930s, since the early 1960s the Polish-Jewish writer and visual artist’s oneiric short stories have been translated and retranslated into almost forty languages, despite their seemingly untranslatable style: an exquisitely rich poetic prose, comprised of meandering syntax and multi-tiered metaphors. In English-speaking countries, Schulz’s name was made in the late 1970s, when his Street of Crocodiles, first published in English in 1963 in both the UK and the US (the British edition was titled Cinnamon Shops, following closely the original Polish Sklepy cynamonowe), was reissued in Philip Roth’s influential Penguin series Writers from the Other Europe (1977), alongside Milan Kundera and other authors from behind the Iron Curtain whom the West had yet to discover. Schulz’s second story collection, Sanatorium under the Sign of the Hourglass (Polish: Sanatorium pod Klepsydrą), followed shortly (1978), and ever since then both volumes have been regularly republished and reprinted, as well as in series such as Picador Classics (1988), Penguin 20th Century Classics (1992), and Penguin Classics (2008).

This summer, the Northwestern University Press announced that “an authoritative new translation of the complete fiction of Bruno Schulz” by Madeline Levine, Professor Emerita of Slavic Literatures at the University of North Carolina, is forthcoming in March 2018. Commissioned by the Polish Book Institute and publicized already since 2012, this retranslation has been impatiently awaited, especially by Schulz scholars dissatisfied with the old translation by Celina Wieniewska. Indeed, it’s great that Levine’s version is finally going to see the light of day—it is certainly going to yet strengthen Schulz’s already strong position. Unfortunately, the preferred (and easiest) way of promoting retranslations is to criticize and ridicule previous translations and, more often than not, translators. Even though the retranslator herself has spoken of her predecessor with much respect, showing understanding of Wieniewska’s goals, strategies, and the historical context in which she was working, I doubt that journalists, critics, and bloggers are going to show as much consideration.

In an attempt to counter this trend, I would like to present an overview of the life and work of Celina Wieniewska, since I believe that rather than being representative of a certain kind of invisibility as a translator (her name brought up only in connection with her ‘faults’), she deserves attention as the co-author of Schulz’s international success. Much like Edwin and Willa Muir, whose translations of Kafka have been criticised as dated and error-ridden, but proved successful in their day, Wieniewska’s version was instrumental in introducing Schulz’s writing to English-speaking readers around the world. Before Levine’s retranslation takes over, let’s take a moment to celebrate her predecessor, who was a truly extraordinary figure and has been undeservedly forgotten.

In Review: Grzegorz Wróblewski’s Zero Visibility

"Poems that, like objects on a beach, one can pick up, briefly examine, and set back down again."

While preparing to write this review, I came across an interview with Grzegorz Wróblewski in the Polish literary website Literacka Polska that began:

Rafał Gawin: For Polish readers, especially literary critics, it’s as if you’re a writer from another planet.

Grzegorz Wróblewski: Yes, it can seem that way from a certain distance. [My translation]

I think it’s safe to say the case is also true for English-speaking readers—Wróblewski’s most recent collection, Zero Visibility, translated by Piotr Gwiazda, really does feel like encountering a voice from a different world, albeit one that deals with all too real human (and often animal) concerns. Even on a surface reading it is clear that Wróblewski’s poems exhibit a remarkable range of tone, veering between seriousness and satire, surrealism and objectivity, grandiloquence and quiet, interior reflections. The first two poems, “Testing on Monkeys,” and “Makumba,” with their manic repetition and loud exclamations, are perhaps the two most frenetic and high-powered poems in the collection; they are suddenly followed by poems that are short and obscure, often dream-like and hallucinatory such as “The Great Fly Plague,” where “We abandoned our fingernails on the warm stones” or “Club Melon” which has “clones drinking juice made of organic, perfectly pressed worms”—poems that are at first disorientating, but at the same time openly invite the reader to attempt further interpretation.

Some of the best poems in the collection are the ones that, to put it bluntly, are about something recognisable, but also take time to construct and develop their ideas, such as “‘Bronisław Malinowski’s Moments of Weakness,”:

If I had a revolver, I’d shoot a pig!

A scholar’s clothes shouldn’t attract suspicions. Malinowski ordered

two Norfolk jackets from a tailor on Chancery Lane. Also a helmet

made of cork, with a lacquered canvas cover.

In one letter he wrote: Today I’m white with fury at the Niggers…

If I had a revolver, I’d shoot a pig!

His stay on the Trobriand Islands was pissing him off.

In spite of that, he became a distinguished anthropologist (27).

Another example is “Enhanced Interrogation Techniques,” a multilingual poem which examines methods of torture used at CIA black sites (one of them located in Poland) mixed with news about celebrities such as Tom Cruise and Angelina Jolie:

It wasn’t until he was 39 years old that Tom Cruise decided to straighten and

even out his teeth!

Later, the CIA used additional “enhanced interrogation techniques”

that included: długotrwała nagość (prolonged nudity), manipulacje żywieniowe

(dietary manipulation), uderzanie po brzuchu (abdominal slap).

Two small planes with Poles on board went down (31). READ MORE…

What To Do With an Untranslatable Text? Translate It Into Music

Translators and musicians team up on a sweeping audio interpretation of Finnegans Wake

Finnegans Wake, the final book by Irish writer James Joyce, is a bit like the alien language in the movie Arrival. As the film’s spaceships tower mysteriously over the Earth, so Joyce’s book casts its strange shadow over world literature. Most literary minded people are aware of the text’s presence, but no one actually knows how to read the book, save for a select few who claim it is the greatest thing ever written.

In order to read Finnegans Wake, you must become a translator. You must translate the text out of it’s idiosyncratic, multilingual semi-nonsensical language, and into… music? For example, see Rebecca Hanssens-Reed’s interview with Mariana Lanari, about the process of translating the Wake into music.

For the last three years I’ve pursued the music that is Finnegans Wake. I organize an ongoing project called Waywords and Meansigns, setting the book to music. This week we release our latest audio, which is 18 hours of music created by over 100 musicians, artists and readers from 15 countries. We give away all the audio for free at our website (and you can even record your own passage, so get involved!)

Listen to a clip of the project here!

It might sound strange, but translating the book into music is easier than, say, translating it into another foreign language. But that hasn’t deterred Fuat Sevimay, who translated the book into Turkish, nor has it stopped Hervé Michel, who calls his French rendering a “traduction” rather than a “translation.”

Highlights from the Asymptote Winter Issue

Our editors recommend their favorite pieces from the latest issue.

First off, we want to thank the five readers who heeded our appeal from our editor-in-chief and signed up to be sustaining members this past week. Welcome to the family, Justin Briggs, Gina Caputo, Monika Cassel, Michaela Jones, and Phillip Kim! For those who are still hesitating, take it from Lloyd Schwartz, who says, “Asymptote is one of the rare cultural enterprises that’s really worth supporting. It’s both a literary and a moral treasure.” If you’ve enjoyed our Winter 2017 issue, why not stand behind our mission by becoming a sustaining member today?

*

One week after the launch of our massive Winter 2017 edition, we invited some section editors to talk up their favorite pieces:

Criticism Editor Ellen Jones on her favorite article:

My highlight from the Criticism section this January is Ottilie Mulzet’s review of Evelyn Dueck’s L’étranger intime, the work that gave us the title of this issue: ‘Intimate Strangers’. Mulzet translates from Hungarian and Mongolian, but (being prolifically multilingual) is also able to offer us a detailed, thoughtful, and well-informed review of a hefty work of French translation scholarship. Dueck’s book is a study of French translations of Paul Celan’s poetry from the 1970s to the present day (focussing on André du Bouchet, Michel Deguy, Marthine Broda, and Jean-Pierre Lefebvre) and is, in Mulzet’s estimation, ‘an indispensable map for the practice of the translator’s art’. One of this review’s many strengths is the way it positions Dueck’s book in relationship to its counterparts in Anglophone translation scholarship; another is its close reading of passages from individual poems in order to illustrate differences in approach among the translators; a third is the way Mulzet uses Dueck’s work as a springboard to do her own thinking about translational paratexts, and to offer potential areas for further research. The reviewer describes L’étranger intime as ‘stellar in every way’—the same might be said of the review, too.

Chief Executive Assistant Theophilus Kwek, who stepped in to edit our Writers on Writers section for the current issue, had this to say:

When asked to pick a highlight from this issue’s Writers on Writers feature, I was torn between Victoria Livingstone’s intimate exploration of Xánath Caraza’s fascinating oeuvre and Philip Holden’s searching essay on Singapore’s multilingual—even multivocal—literary history, but the latter finally won out for its sheer depth and detail. Moving from day-to-day encounters with language to literary landmarks of the page and stage, Holden surveys the city’s shifting tonalities with cinematic ease, achieving what he himself claims is impossible: representing a ‘polylingual lived reality’ to the unfamiliar reader. And as a Singaporean abroad myself, Holden’s conclusion sums it up perfectly: the piece is ‘a return to that language of the body, of the heart’.

Visual Editor Eva Heisler’s recommendation:

Indian artist Shilpa Gupta addresses issues of nationhood, cultural identity, diaspora, and globalization in complex inquiry-based and site-specific installations. The experience of Gupta’s work is explored by Poorna Swami in her essay ‘Possessing Skies’, the title of which alludes to a work in which large LED light structures, installed across Bombay beaches, announce, in both English and Hindi, ‘I live under your sky too.’ Gupta’s work, Swami writes, ‘positions her spectator in an irresolvable conversation between the abstracted artwork and a tangible sense of the so-called real world, with all its ideologies, idiosyncrasies, and fragilities’.