“A good reader, a major reader, an active and creative reader is a re-reader,” Vladimir Nabokov reminds us in his article “Good Readers and Good Writers”. There are so many books in this world, and unless your life revolves solely around books, it might be hard to be widely read and an active re-reader. Attaining this level of perfection that Nabokov describes is impossible, but the idea of re-reading as a tool to better understanding the value of a book underpins the philosophy of the Man Booker Prize International’s judging panel since its inception.

On the evening of April 12, Lisa Appignanesi, the chair of the judging committee, announced the six shortlisted titles from Somerset House in London. To arrive at the announced shortlist, the judges spent the month between the unveiling of the longlist and April 12 reading (now for the third time) all thirteen longlisted titles. There is no official checklist that facilitates the judges’ pursuit in selecting an example of “fiction at its finest” as the Man Booker tagline describes its self-imposed mission. During the official announcement, Appignanesi mentions, however, that they were looking for books that “endured in our imagination”, reiterating the importance re-reading has for the judging process.

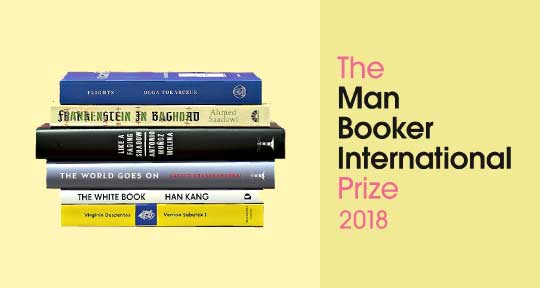

According to the judges, these books are “only united in diversity. There are books with very strong narrative, books with lyrical atmosphere as their forefront, and books with a real density of metaphysical preoccupation.” Linguistically, the list is as diverse as it could get (when taking into account the limitations of the original longlist). Unlike the longlist, there were no repeats in the shortlist, with the books representing six different countries and six different languages: France (Virginie Despentes with Vernon Subutex 1), South Korea (Han Kang for The White Book), Hungary (László Krasznahorkai for the World Goes On), Spain (Antonio Muñoz Molina for Like a Fading Shadow), Iraq (Ahmed Saadawi with Frankenstein in Baghdad), and Poland (Olga Tokarczuk for Flights).

In my last piece on the topic, I predicted that the shortlist, based on past selections, would surprise dedicated followers of the MBI. Judging by the discussions of dedicated readers on Goodreads and across personal blogs, that seems to be the case. Despentes’s Vernon Subutext 1 has been described by one reviewer as the “marmite” of books, splitting opinion with its depiction of one slice of contemporary Parisian society. The narrative follows Vernon Subutex’s descent into homelessness, as he makes his way around the city finding temporary shelter with past acquaintances. To those accustomed to classic French fiction, reading Despentes can be a shock: her language is unvarnished and her characters speak in a chorus of curses. Ultimately, this book is a depiction of human loneliness and speaks directly to issues affecting contemporary Paris, socially and politically.

Speaking of political relevance, no other book can top Frankenstein in Baghdad for the place and attention it holds within the literary community this year. 2018 marks the fifteenth anniversary of the start of the Iraq War, a war whose human consequences this book depicts in depth. Hadi, a junkyard collector in modern Baghdad, has constructed a ‘monster’ out of disparate body parts, accumulated after murders and explosions hit the city. When the monster gains sentience and begins his quest to avenge the owners of his composing body parts, the characters in Saadwi’s diverse Baghdad (including an elderly woman, a journalist on the rise, and an ambitious brigadier) are forced to rethink their past beliefs and behavior. Frankenstein in Baghdad is a commentary on the fickle nature of justice, just as much as it is a modern-day fable.

My personal favorites (and it seems those of readers in spaces like Goodreads groups, or the Shadow Panel—a jury of prolific personal bloggers that review the longlisted books on their own terms) are Han Kang’s The White Book and Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights. They are both atmospheric books, untethered to the idea of plot and narrative in the traditional sense. Flights is organized around short stories and meditations on travel and the human body. It is populated with characters that seek to escape, yet almost always come back home only to realize that travel changes you and the home that you left is no longer the same. It is almost an antidote to the human penchant toward nostalgia. The White Book, on the other hand, gives a home and a life within its pages to the sister Kang never had. Like Flights, it is a meditation on the fleeting beauty and nature of all that is human.

On the flip side, the inclusion of Krasznahorkai and Muñoz Molina was a bit unexpected. Both authors are authoritative figures in the world of literary fiction yet reviews of both The World Goes On and Like a Fading Shadow describe them as not the authors’ best work. Nevertheless, speaking to Joe Haddow for the official Man Booker podcast, two of the judges (Appignanesi and Michael Hoffman) praised The World Goes On, a collection of short stories and essays in Krasznahorkai’s signature style, as the writer at “his most profound and most approachable,” demanding the reader’s attention in ways traditional novels no longer require of us. Muñoz Molina is also admired for his ability to translate character in a narrative that shows the writer at his most vulnerable and asks how we can reinvent and understand someone we have never met.

***

The judges of the Man Booker Prize promote the idea that books are chosen based on literary merit, without, so to speak, outside constraints. But among critics there is this sense that the MBI has an inherent duty to it, beyond merely awarding the final accolade to the year’s best translated fiction. Due to its prestige, winning the Man Booker Prize expands the reach of the winner’s readership. And not just the winner: oftentimes merely being included in the shortlist can have significant financial advantages. As such, there is a push to take into consideration past achievements and future potential of the individual authors when making the decisions to shortlist certain titles.

This has been the case with the omission of Ariana Harwciz’s Die, My Love, which disappointed a lot of readers and was included in the Shadow Panel’s shortlist. The story is told almost entirely from the perspective of an unnamed woman going through a depressive crisis after the birth of her first child. The narrator is unreliable, her mental state shifting the perspective at every turn, and yet for all its uncertainties, it is beautifully written and translated. A second read would be required to appreciate it fully. Yet, those who wanted to see it make the shortlist looked beyond literary merit. This is Harwciz’s first novel and is published by the young Charco Press, an independent publishing house that publishes only new voices in Latin American literature.

The judges of the Man Booker Prize are well aware of such criticisms and Lisa Appignanesi has addressed the topic on at least two occasions, when asked whether Krasznahorkai and Han Kang (both past winners of the prize) should be included on the list at the expense of lesser known authors. Speaking on the Man Booker Podcast, Appignanesi argued this “seems to be a mistaken assumption” and if the prize worked under these parameters then “you’d have to say that you weren’t judging for fiction, but for newcomers… And these weren’t rules of [the MBI].” Under such premises, the only things that matters to the current judging panel is a book’s literary worth, its ability to survive various bouts of re-reading and capture the reader’s imagination.

Of course, when it comes down to things like literary merit, the matter becomes more complicated, as the parameters can be uncertain. Based on this year’s shortlist, Flights, The White Book, or even The World Goes On stand out for their ability to express through their writing the pains of being human. Frankenstein in Baghdad and Vernon Subutext 1 are a bit more visceral, their politics (social, sexual, personal) are at the forefront and are unapologetic in their directness. As the judges themselves mentioned, this is a highly subjective exercise, as reading always is. Re-reading as a balancing tool can only take you so far, as Appignanesi reminds listeners on the podcast: what we take out of a book changes as “your own being in the world is not the same” every time you pick up a book to read or re-read.

Watching the live event, there was a particularly strong applause when Appignanesi announced Frankenstein in Baghdad as part of the shortlist. The literary world likes the idea of a book about Baghdad reaching readers across all spectrums in the current political climate. It could very well win the prize on May 22. Yet, the judges have gushed about The World Goes On, agreeing that there are worse things than being stuck inside one of Krasznahorkai’s longwinded sentences “for the rest of your life.”Appignanesi, meanwhile, praised Tokarczuk’s Flights, saying she “wish she could write it.” In the midst of such uncertainty, I am refraining from making a final prediction. Tune in back in May to find out who won.

Barbara Halla is Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Albania. Originally from Tirana, she currently resides in Paris where she works as a freelance editor and translator for French, Italian, and Albanian. She holds a BA in History from Harvard.

*****

Read more essays: