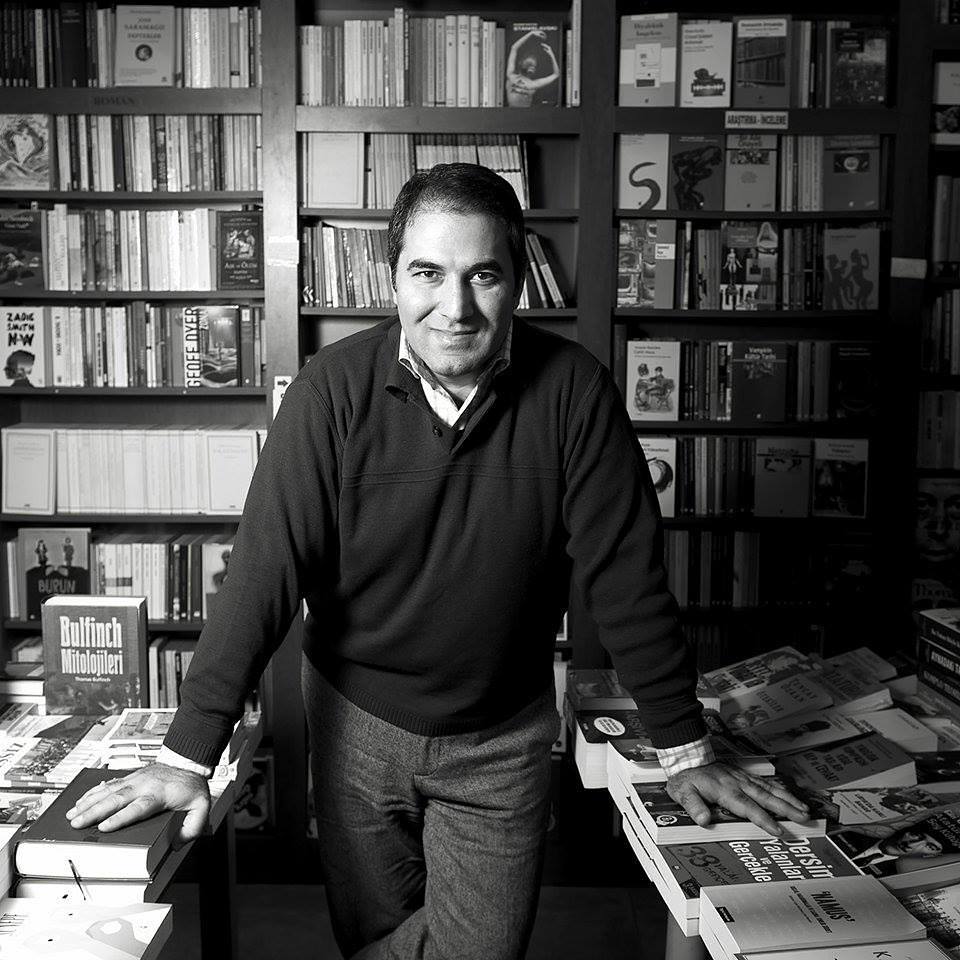

Despite his relatively recent arrival in the Turkish literary world, Fuat Sevimay is a highly promising writer and translator. After graduating from Marmara University with a degree in business and working as a sales manager for two decades, he began writing in his spare time six years ago “just to get rid of boredom.”

Sevimay was encouraged to keep writing, however, because his work quickly began to garner awards. In 2014, his short story collection Ara Nağme won the Orhan Kemal Short Story Book Prize, one of the most prestigious literary awards in Turkey, and in 2015, his novel Grand Bazaar won the Ahmet Hamdi Tanpinar Novel Prize. His novel AnarŞık was also adapted for the stage this year, premiering last month in Istanbul. A devoted father of two, Sevimay has also written numerous children’s books, including Haydar Paşa’nın Evi.

Sevimay has translated two of Italo Svevo’s novels, Senilità and La Novelle del Buon Vecchio E Della Bella Fanciulla, from Italian. Sevimay has also translated Oscar Wilde’s 1891 essay “The Soul of Man Under Socialism,” Pandora by Henry James, James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man and the collection of Joyce’s essays entitled Occasional, Critical, and Political Writing. In 2015, Sevimay was the Translator-in-Residence at Trinity College Dublin, hosted by the Ireland Literature Exchange and the Centre for Literary Translation.

Over a course of emails we interviewed Sevimay about his current project, translating what may very well be the most complicated book ever written, James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake.

***

Derek Pyle and Sara Jewell: Fuat, thank you for taking the time to answer a few questions. Let’s start with hearing a bit more about yourself. What is your background as a writer and translator?

Fuat Sevimay: To be frank, I never dreamed of becoming a writer or translator. Until six years ago, I had been working as a sales manager and was simply a good reader. Then I wrote a story just to get rid of my boredom. If I had a nice voice instead, I could try to sing but it would be a kind of torture for my friends. The story was not bad. I made some redactions and then sent it to a competition. Two months later, someone called me and told that my story was awarded. Let’s call it fate. Then I had novels, a short story collection, books for children and some translations published, including Portrait of the Artist and Joyce’s Occasional, Critical, and Political Writing.

DP & SJ: You’ve translated A Portrait of the Artist, and now you’re working on Finnegans Wake. How did you first become interested in James Joyce?

FS: Before the Portrait and Finnegans Wake, I translated the Occasional and Critical Writings of Joyce (also published as Occasional, Critical, and Political Writing) into Turkish. This was a great opportunity for me to get in touch with the idea since Critical and Occasional Writings were not fiction, differing from Portrait, Dubliners or Ulysses. You can sense the non-author James Joyce in those texts—his interests, political view, literary taste and his relation with other disciplines of art. I had the chance to feel why he admired Henrik Ibsen and Irish poet James Mangan so much, and why he criticized literary world’s interest in Dickens. What he thought about Ireland include major historical concepts such as Fenianism, Parnell, Home Rule, the state and the society. All those helped me to sense how Joyce’s literature—aside from his life—was shaped in his mind. So I followed the footsteps of Joyce which first led me to Portrait, a semi-biography, then I lost and found myself back in Finnegans Wake.

DP & SJ: When did you begin translating the Wake?

FS: It was by the beginning of 2014 and at that time I did not yet have the idea to translate the whole text. All my effort was just a kind of trial for the first few pages, to test myself and to get an idea about why that masterpiece is an untranslatable one. But when I felt that I could progress, I shared those couple of pages of translation with some friends. One of them—Aziz Gokdemir, who also lives in the US—said, “Ah yes, this is exactly Joyce in Turkish.” Thanks to that encouragement, the translation is still in progress and hopefully we will have Finnegans Wake in Turkish, most probably within a year.

DP & SJ: Tell us more about Joyce’s readership in Turkey.

FS: When I was in Ireland, I had the chance to talk about Joyce and Finnegans Wake with Irish people and some other native English speakers. What I saw there was that they love Joyce and admire his work but mostly have not read it, or they attempted to read it but have given up. Joyce’s destiny is similar in Turkey when compared with the rest of the world. Just to give an idea, Ulysses sold more than 300,000 copies in Turkey, which is a remarkable quantity. However, when the subject is Joyce and his novels, being admired, being bought, being read and being understood are totally different aspects. I hope that translation of Finnegans Wake will refresh and increase the interest in Joyce.

DP & SJ: In general, what do you think is the most important aspect of the original work that should be preserved during translation?

FS: Certainly the motifs and the leitmotifs. When you attempt to translate—or interpret—Finnegans Wake, you have to be aware that, inevitably, you will lose some points at the source and you have to gain some others in your target language. But you don’t have a choice and cannot miss the motifs since they are the cues for an extremely complex novel. The reader—if careful enough, determined and willing—can follow a protagonist or a repeated event through motifs. Readers could feel free to pay or not to pay enough attention, but as a translator, I must and do pay my utmost attention to motifs.

DP & SJ: What did you find to be the most difficult aspect to grapple with in your translation of the Wake?

FS: Most probably the Joycean words. Let’s think about it. He, the master builder, says something in so-called English but the same word indicates something else if you read half of it in Gaelic and the rest in Latin. You have to correspond all three of them and if, in a way you succeed—bad news—that’s not enough. Your word has to get the right syntax within the sentence and—worse news—it still may not be enough. You also have to catch the phonetic. Oh, I’m tired. But Finnegans Wake deserves it all.

DP & SJ: Perhaps you can pick a particular passage of the book and outline for us how you worked with the multilingual aspects?

FS: To be frank, my priority is not the multilingual nature of Finnegans Wake. I mean, I try my best for such words but when I feel kind of kakafoni, I give up and translate them to Turkish. But for some specific sentences or paragraphs, I like to use various languages spoken within the environment of Turkey. Maybe you remember the thunder of Joyce at the very first page, which in fact is the composition of thunders from many languages. I have translated it as “gümbürpatırdara’dgurgulalivirhatditinvorodumvrodinprasakgromakukhilişıbleğoğomakdagürülgökgürültüsü”. We have Turkish, Greek, Arabic, Armenian, Farsi, Caucasian and some other regional thunders within it. [Editor’s note: the first thunder word in Joyce’s original text reads “Bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthur-nuk!” Finnegans Wake, 3.15-17.]

DP & SJ: Do you find that there is a unique or particular musicality to Joyce’s writing? Can aspects of the writing so closely tied to sound, like phonetic spellings, be successfully brought across in translation?

FS: Well, we all know Joyce’s answer to the humble reader, who confessed to Joyce that he tried but could not understand Finnegans Wake. The answer was, “Then just listen to it”. I think that Joyce’s aim with Finnegans Wake was much more than writing a wonderful novel (he already had written one previously). He tried to catch the sounds within the history of humanity. Thus, I personally always prefer to listen to Finnegans Wake—from Waywords and Meansigns—rather than reading it. For the Turkish translation, I would love to match a similar musicality within Turkish’s own linguistics and study it.

When we talk about musicality, I have to mention that I find some similarities between Finnegans Wake and the scene in Back to the Future with Marty playing guitar on the stage at the ball, towards the end of the film. He has gone back to fifties and to help his mother and father fall in love. So on the stage he performs so well at the beginning and that’s Portrait of an Artist. Then he starts to play something from sixties, some Elvis, which is new to the people but they’re bewildered and love that. This is Ulysses. Finally he can’t help himself, playing a wonderful hard rock solo from eighties, eyes wide shut. And at the end of his performance when he opens his eyes, people are shocked, astonished. And that is Finnegans Wake.

Regarding phonetic spelling, if you focus on your target language, its labials, genitives, semantic, agglutinative form, yes, mostly you have the chance to catch the sound. Neydi vurun ha diyenlerle durun ha diyenleri kapıştıran, hastrigotlarla vizigotları kızıştıran! Vrak da Vurak, Kak Kak Kubarak, Geberek göverek! Ulayiğit ulaslan ulaoğul ulagitti! Vah eyvah! Ah, sorry for the confusion, do not blame your receiver, it’s just Turkish. I just hope that you enjoyed the sound. This part in Turkish is again from the first page. [Editors note: Joyce’s original text reads, “What clashes here of wills gen wonts, oystrygods gaggin fishy-gods! Brékkek Kékkek Kékkek Kékkek! Kóax Kóax Kóax! Ualu Ualu Ualu! Quaouauh!” Finnegans Wake, 4.1-3.]

DP & SJ: Various theorists have questioned whether any literary work can actually be translated, or if all “translations” are actually derivative works. Joyce, on the other hand, was once quoted by Richard Ellman saying that there is nothing that cannot be translated. These questions seem most pertinent, perhaps, in the case of the Wake. Is a translation of Finnegans Wake actually Finnegans Wake, or is it some new work, albeit one linguistically inspired by Joyce? In other words, how much of your translation is Joyce, and how much of it is your interpretative spin on the Wake?

FS: In general, I think that even madness can be translated. Thus, arguments against translatability or evaluating translations as derivative works are mostly nonsense. Or let’s say that such academic details are not in my scope. Translations are, in a way, cooperation of the writer and translator. If they are both good, cheers. Specific to Finnegans Wake, I would like to repeat Italian Finnegans Wake translator Schenoni’s words. He says, “Translating Finnegans Wake is to give your interpretation of the work, one of the infinite possible ones, into your own language.” I personally feel myself as a mediator for Joyce and the reader. For a regular novel, translation theories, various rules, norms, and limits may mean and sound like something. But when it’s Finnegans Wake, let’s just enjoy the peak.

DP & SJ: Translations are often deemed necessary in order to make a work more accessible to readers who can’t read the author’s original language. Translations of Finnegans Wake, however, sometimes appear as ultra scholarly texts, with extensive notes and annotations. Who do you envision as the audience for your translation?

FS: I had the chance to study five other Finnegans Wake translations in other languages, and for some of them you have the right to identify them as scholar texts. In fact, when you try to explain Finnegans Wake, even 6,280 pages could not be enough. Thus, I don’t plan to use footnotes or annotations. However, if you prefer to publish only the text with nothing else, there’s always the risk for the reader not getting involved (I do not mean ‘understanding’).

To assist the reader but not to interfere with the reading pleasure, I will only have some brief comments and reminders for each part; and, to arise the interest, I plan to point out some—just a few—specific tricks of Joyce which would incite the reader to trail others. So I would love to serve any reader who is ready to read what is definitely the most interesting and best book ever written, and will feel so happy if one day, one of them says that Joycean Turkish was delicious.

DP & SJ: Once you’ve completed translating the Wake—which is a lot like climbing the Mount Everest of translation—what’s next for you?

FS: I will have a deep breath, then would enjoy the wonderful and unique scene for a while and then, before freezing, climb down to write my own novel. I also plan to have a study on Turkish in Finnegans Wake together with the philology department of a university. Finnegans Wake includes quite sufficient material for such a work.

One day I attended a Finnegans Wake reading session at Sweny’s. Ulysses readers would remember Sweny’s as the drugstore in Dublin in which Bloom buys soap. All other readers were English speakers besides myself, and I couldn’t help but laugh at a sentence. The reader ceased reading and others looked at me and I had to explain that the last sentence about ‘the most reverend York bishop’ [Editor’s note: in Joyce’s text, “watarcrass shartclatchs aff the arkbashap aff Yarak” Finnegans Wake, 491.17.] was indicating totally something else when it was read in Turkish. So, lots of fun also at Fingene; Finnagain in Turkish.

*****

Derek Pyle is director and producer of Waywords and Meansigns, an international project setting James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake to music unabridged.

Sara Jewell is a student at Hampshire College, where she is studying graphic narrative. You can support work on her upcoming graphic memoir. Sara is design and communications specialist for Waywords and Meansigns.

Read more from Turkish Literature:

- Translation Tuesday: “Spring’s Doings” by Orhan Veli Kanık

- Melih Cevdet Anday, from A Poem in the Manner of Karacaoglan

- Hakan Savlı, from Only for Music