In this month’s round up of the latest releases, we’re thrilled to introduce three singular works from rulebreakers, free thinkers, and true originals. From Japan, an early novella from the nation’s renowned enfant terrible, Osamu Dazai, gives a telling look at the writer’s internal monologue. From the Nobel laureate Issac Bashevis Singer, a bilingual edition of the Yiddish author’s story—in multiple translations—opens up an inquest into the translator’s pivotal role. And from the Ukrainian émigré Vasili Eroshenko, a collection of the author’s fairy tales, translated from the Japanese and Esperanto, presents a well-rounded selection of the transnational author’s politically charged work. Read on to find out more!

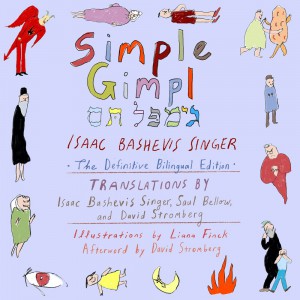

Simple Gimpl by Isaac Bashevis Singer, a definitive bilingual edition with translations from the Yiddish by Isaac Bashevis Singer, Saul Bellow, and David Stromberg, and Illustrations by Liana Finck, Restless Books, 2023

Review by Rachel Landau, Assistant Editor (Poetry)

Whether you choose to know him as “Simple Gimpl” or “Gimpel the Fool,” the main character of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s novella is a likable, rambling man who finds himself in an unfortunate situation. His wife, Elka, is frequently using their shared home for affairs with other men, and all of Gimpl’s attempts to come to terms with the situation are complicated by his deep love for her. Even when the pair are forbidden by the town rabbi from seeing each other, Gimpl works tirelessly to provide for the children and for Elka. He feels betrayed to learn, at the end of Elka’s life, that the children were not really his—and his reaction to this deception is a surprising one.

The narrative in Simple Gimpl is slow-moving, reflective, and witty. It is an undeniable pleasure to read—and certainly not difficult to read multiple times in a row, as this edition of the book incites the reader to do. This “definitive bilingual edition,” released by Restless Books, includes back-to-back translations of the Yiddish work; first is Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Simple Gimpl,” which is followed immediately by Saul Bellow’s “Gimpel the Fool,” and this compendium of translations is decidedly about translation itself. Over the course of more than one hundred pages, one must realize that this is not a book about Gimpl, and not even about the differences between Saul Bellow’s Gimpel and Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Gimpl. It is about the role of the translator; it is about the strange impossibility of rendering a story. READ MORE…