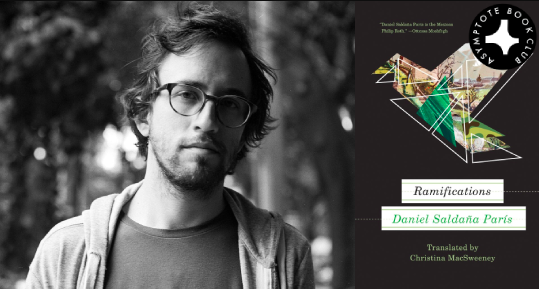

It is perhaps fitting (though regrettable) that our October Book Club announcement has been somewhat delayed: Daniel Saldaña París’s Ramifications is all about holdups. Via Christina MacSweeney’s seamless translation, the acclaimed Bogotá39 writer gives us a counter-formative tale that is both masterfully constructed and poignantly penned. In it, he exposes existential and political conservatism without dealing cheap blows, and introduces readers everywhere to a profoundly relatable narrative voice.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

Ramifications by Daniel Saldaña París, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney, Coffee House Press, 2020

Ramifications opens with a brilliant gambit; within a handful of paragraphs, it both sets up and crushes the prospect of a bildungsroman. A grown narrator feeds us the near-requisite opening, the painful loss at a much-too-tender age: in 1994 his mother, Teresa, flees their home in Mexico City, leaving ten-year-old him and teenage sister Mariana in the care of an oblivious father. Just a few lines later, though, we get a sharp taste of his current predicament—far from being the seasoned, thriving type mandated by the genre after years of fruitful struggles, he defines himself as “an adult who never leaves his bed.”

The rest of the novel artfully explores the tension between the classic formative tale and its antithesis. Parts one and two delve into Teresa’s disappearance and her young son’s attempts to make sense of it, culminating in what could have been an archetypal “journey of self-discovery”—he tries to follow her to Chiapas, where she’s run off to join the budding zapatista movement. Part three, by contrast, hones in on the trip’s bland aftermath, both instant and deferred. It’s not as tidy as that, of course (the narrator jumps back and forth in time), but there’s an overarchingly grim shift from promise to flop. It’s made all the starker by a series of deliciously clever winks from the author: the protagonist’s childhood neighborhood and school are literally called “Education” (“Educación” and “Paideia,” respectively), and he’s thirty-three at the time of writing—an age that, for culturally Catholic audiences at least, can’t help but trigger unfavorable comparisons.

A disclaimer, lest readers think I’ve spoiled the plot: the novel doesn’t ride on events. It is, at its core, an absorbing character study, driven not just by voice (more on that later) but by a deeply original theme: (a)symmetry as a curb on growth. READ MORE…