I met Chia-Lun Chang when we were both enrolled in the Poets House fellowship program in 2016, when I had only been writing for a few years and was hesitant to call myself a poet. We bonded over how new we were to writing poems. In this following conversation, we retraced her unconventional introduction to writing poetry and how English as a second language offered her a newfound identity to be playful and purely honest. Her book Prescribee (Nightboat Books, 2022) wields humor like a dagger, rife with cutting repartee that reveals how cruel, yet liberating life is for her in America. Her poems from the book have appeared in Granta, The Brooklyn Rail, and BOMB online.

Chia-Lun Chang (CC): In Taiwan, the genres are not as distinct as in America, but I noticed that many high-profile writers in Taiwan primarily write non-fiction prose, expressing their opinions. Readers think of it as culturally significant; it provides a getaway into the lives of another world, a world full of writers or cultured individuals. During our conversation, I’ve also realized that many novelists are telling one story. They have numerous novels, but it’s one same story from a core idea because it originates from their body.

Anne Lai (AL): Do you feel like you’re also in pursuit of one idea when you’re writing?

CC: Because of my experiences, I tend to question my identity. But, aren’t we all, in some ways, asking ourselves, “Who am I?” In that very question, I’m afraid of finding the unknown. There are moments when I write in English, where I create a new persona that reflects this nation and the body that I inhabit within it. That is the direction I’m heading and it’s tied to my identity, this very new role that I’m cultivating.

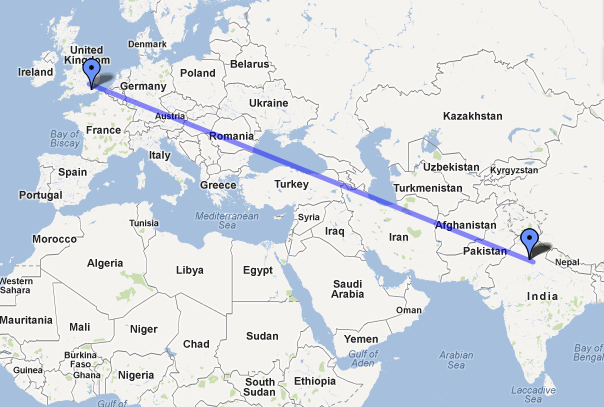

AL: This reminds me of your experience in trying to get your green card, and eventually getting it.

CC: Yeah, both of those experiences—applying for a green card and learning the language that I speak most of the time. The green card process was brutal so I was constantly facing a blackhole answer: what’s necessary for me to stay? I’m terrified of my desire. I don’t believe I have the opportunity to create art in Taiwan, I’m not talented enough or I don’t have space to do what I’m doing here, and many may disagree. But I’m grateful that I can be playful and try different things in this new language and space.

AL: I’ve never asked you this, but have you written poetry in Mandarin? How did you start writing?

CC: Never. Growing up, I was always interested in writing, but I saw myself more as a reader. There were times when I would write essays for school; the requirements of exams in Taiwan were like the SAT tests in the States, but they asked for more melancholic and metaphorical compositions. Those were my experiences in building my first language. I remember the question on my college exam was, “Who is your idol? Who do you look up to?” I actually wrote about the poet Su Shi. In my society, I felt that people had a moral obligation in writing; they had to be heroic—even in love, in pain, or struggling. Deep down, I have a cynical personality and worry about not being accepted by society. READ MORE…