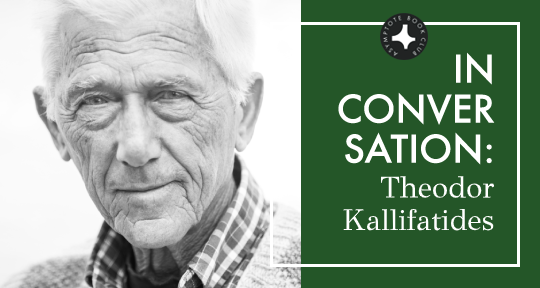

In September, we were honored to present Theodor Kallifatides’s The Siege of Troy as our monthly Book Club feature. This poignant, multilayered novel intertwines a modern coming-of-age wartime story with a psychologically profound retelling of the classic Iliad. In the following interview, Assistant Managing Editor Josefina Massot speaks with the author on overcoming writer’s block, writing about Greece in a foreign land and tongue, and humanizing ancient heroes.

Josefina Massot (JM): You had an unexpected bout of writer’s block at age seventy-seven, back in 2015, after almost fifty years of uninterrupted literary output. The Siege of Troy was, I believe, the first novel you wrote once you overcame it. Did your writing process change at all as a result? What was it like, rediscovering your narrative voice in novel form?

Theodor Kallifatides (TK): Yes, it affected me and my writing greatly. I felt free from all expectations, from all demands from the publisher, the public, and myself, and my writing got wings it never had before. I did not care about anything except doing justice to my deepest feelings and ideas. I got back both my eyes. Before it, I always had—as most writers do, I dare say—an eye on what people would think about my work. Suddenly, I simply did not care. I was free.

JM: In 2016 you wrote your autobiographical essay Another Life in Greek, and that helped you break through your block. You then tried translating it into Swedish, but ended up rewriting it because “in order to be anywhere near good in Swedish, it had to be changed [. . .]. The world of one language was different from the other. So was the rhythm. And the idea of time, the sense of timing [. . .]. Each language is unique.” As a prolific bilingual writer and translator, could you elaborate on some of these differences between Swedish and Greek, and how they’ve affected your writing? Why do you think that going back to Greek after decades of writing in Swedish allowed you to regain your creative “flow”?

TK: A language is like an iceberg. You see only the top of it. Let me give a simple example. The word “window” is “fönster” in Swedish and “paráthyro” in Greek. They name the same thing, but while the Swedish word points to a certain thing, the Greek word evokes an ocean of memories from folksongs, tales, and your life. The face of the girl you loved when you were fifteen years old and you saw her there, and you thought she was waiting for you to pass by but she was expecting somebody else. You recall the closed windows during the German occupation of your village, when women and children cried for husbands and fathers that had been killed or executed. You recall the pots with basil on the wide-open windows of happy days. Now, is the Swedish word a translation of the Greek word? No. It is not, and as a writer you try to find ways to minimize the difference. Going back to my first language was like going back to my true self, which of course is not entirely true, but it felt like that.

JM: “Homesickness might not be a real illness, but it has the same debilitating effect on all of us,” says Miss in the novel. She later adds, “It is one thing to fight on home ground, a different matter entirely to wage war in a foreign land.” Is writing like war in this sense? In particular, how has writing about “home” (Greece) in a “foreign land” (Sweden) impacted your work? Has “homesickness” played a big role in it all, and if so, has it been overall debilitating or empowering?

TK: Writing in another language about my country was the only way to do it. It was too painful to write about it in Greek. Going over to Swedish gave me the necessary distance. Of course, that also had a price. My writing became more objective but also alienated. It was like looking at a picture and writing about it instead of looking at reality. The reality just hurt too much. The homesickness remains a part of my daily life. It hits me without warning any hour of the day or night. To struggle with it like that is exhausting but also very inspiring. I have the pain but it is rewarding.

JM: Your rendition of The Iliad in the novel was an act of translation itself: from Ancient Greek into Swedish, from epic poem to prose. You also made a series of creative choices regarding content: the war breaks not because Paris abducts Helen but because Helen falls in love and chooses to elope with him, for instance, and a great deal of emphasis is placed on the relationship between Achilles and Patroclus. How and why did you arrive at what you wanted to say and how you wanted to say it?

TK: It actually took more than ten years to figure out how I should do it. The Iliad is the greatest antiwar poem I know, and war is a human matter. I wanted to write the pain, the agony, the barbarism of war. I did not want to write a heroic story. Heroes are interesting when they are humanized. Helena is not only a beautiful woman; she is also a foreigner in the country of her lover, and Achilles knows that he is going to die in that war. I wanted to write about them as human beings, not as superhuman. And I wanted at the same time to make the modern reader conscious of Homer’s great poetry. So I brought together my village under the German occupation and the Trojan War. The German captain and Achilles. The differences are not so great as one would think.

JM: The themes of love and war are closely intertwined in the novel, both in your rendering of The Iliad and in the wider story that contains it. In what ways do you think these fundamental human forces, eros and thanatos, have changed over the centuries? In what ways have they remained the same?

TK: Well, this is the point. I believe that basic human needs have been the same throughout all of time. The conditions of life change for better or for worse, but the need to love and be loved does not depend on the conditions of life. The fear of death is there too. People can and do overcome it, but that does not mean that they change it. We can learn to cope with it, but that is all. A basic human need is also to remember and be remembered. That is why we put one stone on top of another, we paint, we sing, we write. I have been writing for fifty years and only now I know the answer to the basic question. Why do you write? Well, I cannot help it.

Theodor Kallifatides has published more than forty works of fiction, nonfiction, and poetry that have been translated around the world. Born in Greece in 1938, Kallifatides immigrated in 1964 to Sweden, where he began his literary career. As a translator, he has brought August Strindberg and Ingmar Bergman to Greek readers, and Giannis Ritsos and Mikis Theodorakis to Swedish ones. He has received numerous awards for his work in both Greece and Sweden. He lives in Sweden.

Josefina Massot was born and lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied Philosophy at Stanford University and worked for Cabinet Magazine and Lapham’s Quarterly in New York City, where she later served as a foreign correspondent for Argentine newspapers La Nueva and Perfil. She is currently a freelance writer, editor, and translator, as well as an assistant managing editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: