“What is language if it is not sound?”—Trần Thị NgH

Speaking of translation in one of the pre-recorded sessions of the poetic showcase Ù Ơ | SUO, writer Trần Thị NgH reminded the audience of the importance of sound in language. Sound, she argued, is the space in which an utterance bears meaning.

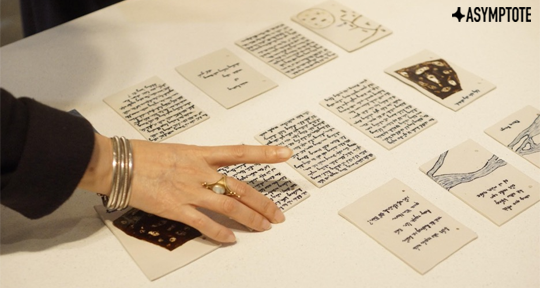

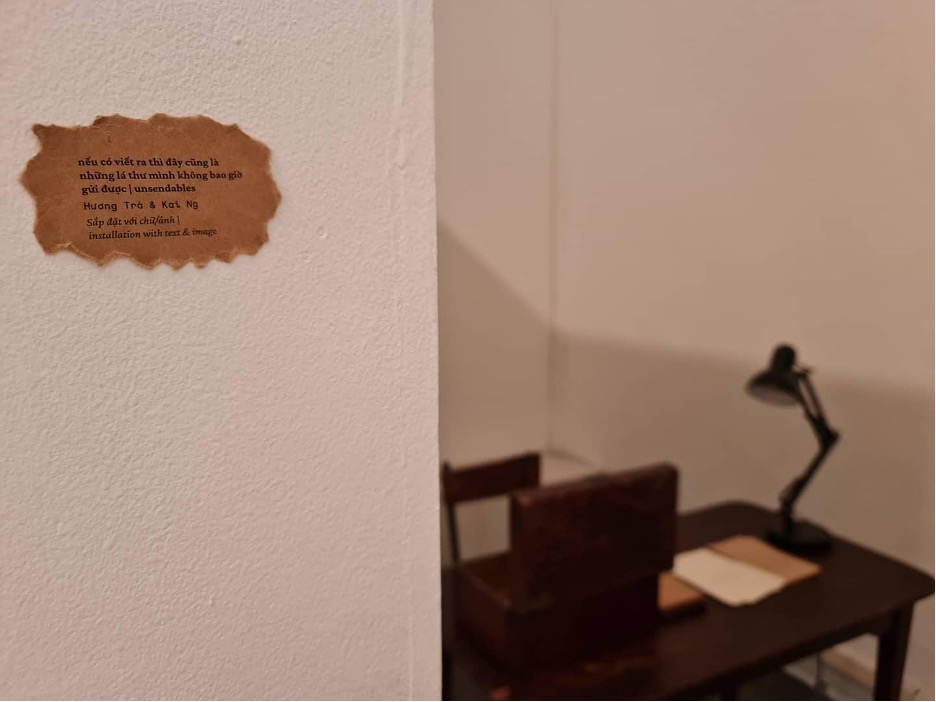

This focus on sound and other sensory aspects of poetry permeated the week-long Ù Ơ | SUO, which brought together poems in translation and multilingual works mixing Welsh, English, and Vietnamese, as well as panel discussions and visual and performative responses. This collaborative work was the result of a three-month residency for Welsh and Vietnamese women and non-binary writers.

Ù Ơ | SUO’s point of departure, according to Nhã Thuyên’s introduction, was the “familiar sounds of lullabies” and how they might serve as a clue to the “origins of poetic language and the role of women in transmission of language and memory within families.” The title of the showcase, which refers to the act of singing a lullaby, inspired me to experience this showcase through the dialectal metaphor of “bercer un poème“: cradling a poem as a mother would a crying child. The reader is also important to the “growth” of the piece: reading is how we cradle a poem. Nous sommes bercés par le poème, et nous berçons le poème—we are cradled by the poem, and we cradle the poem.

As I viewed the exhibition, Piaget’s theory of cognitive development came to mind. His theory deals with the nature of knowledge: how a child comes to acquire it, build it, and use it. According to Piaget’s framework, children go from experiencing the world through actions, to learning how to represent it through words, to expanding their logical thinking and reasoning. It isn’t that children know less, Piaget argued; they just think differently. This thinking “differently” is then a space where creative potential can emerge.