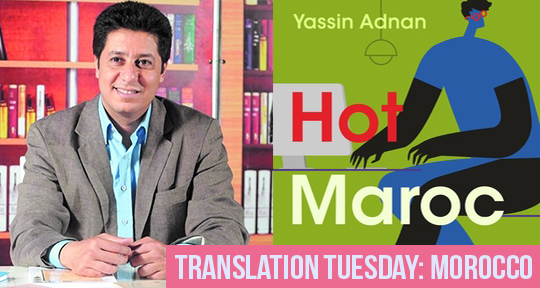

In this month’s selection of excellent literature in translation, there’s something for everyone. From a dreamy and architecturally expressive graphic novel that speaks to fates and futures, to a collection of strange and visceral short stories delineating the network between bodies and their definitions. And if science fiction or unsettling tales aren’t your thing, there’s also the powerful narrative on a prodigal son who returns to navigate the pathos-filled landscape of past tragedies, loneliness, and isolation; the masterfully told history of Catalonia as it plays out through the life of a woman embroiled in the tumult of her time; or a cunning satire of contemporary Morocco that traverses territory of both physical and virtual landscapes. Read on for reviews on each of these remarkable works; hope you enjoy the trip!

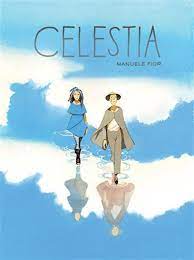

Celestia by Manuele Fior, translated from the Italian by Jamie Richards, Fantagraphics, 2021

Review by Thuy Dinh, Editor-at-Large for the Vietnamese Diaspora

“. . . from above, this island is in the shape of two hands intertwined.”

—Dr. Vivaldi, from Manuele Fior’s Celestia

Such is how Dr. Vivaldi alludes to Venice—curved strips of land yearning to touch and engulf each other in blue space. Ambitiously realized by Manuele Fior and eloquently translated by Jamie Richards, Celestia—Venice’s oneiric double—is a visual poem and modernist dance in graphic novel form, encompassing diaphanous terrains and gothic undertow, exuberantly tumescent with allusions to literature, art, and architecture.

Born in 1975 in Cesena, Italy, Fior currently lives in Paris, France. Drawing from his studies at Venice’s University of Architecture (Istituto Universitario di Architettura di Venezia, or IUAV), he has, over time, developed a dynamic visual language with narrative elements drawn from both Western and Eastern aesthetic traditions. Several of his acclaimed graphic novels have been translated into English and published by U.S.-based Fantagraphics, and Celestia marks his fifth collaboration with Richards—a scholar and translator of Italian literature.

Deeply influenced by John Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice, Joseph Brodsky’s Watermark, and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s poem “Profezia” (“Prophecy”)—Fior depicts Celestia as a fusion of dualities that exist both in the history of Venice as well as in the fictional universe of his work: Gothic and Renaissance, spiritual and secular, traditional and modern, rational and organic, freedom and oppression, community and exile. While in Fior’s earlier work—such as The Interview—telepathy is depicted as an extraterrestial gift, in Celestia this ability has existed from time immemorial among certain people, possibly as an evolutionary process. When the story opens, the island of Celestia is home to a group of telepathic refugees, who long ago fled from a horrific invasion that had devastated the mainland. One of them, Pierrot—cloaked in his commedia dell’arte persona—now wishes to renounce his telepathic power, which he perceives as a tragic link to his childhood. After delivering vigilante justice to a member of the demonic syndicate that controls the island’s murky depths, Pierrot escapes Celestia with Dora—a seer also burdened by her gift, as well as the oppressive intimacy enforced by her mind-melding circle of elites, led by Dr. Vivaldi.

Beset by this innate ability that has become a form of enslavement, Pierrot and Dora set off—hoping their journey would both resolve the past and guide them toward a new future. The couple’s subsequent arrival on the mainland brings them into contact with an omniscient child, or Child—who embodies both the future of mankind and its messiah. READ MORE…