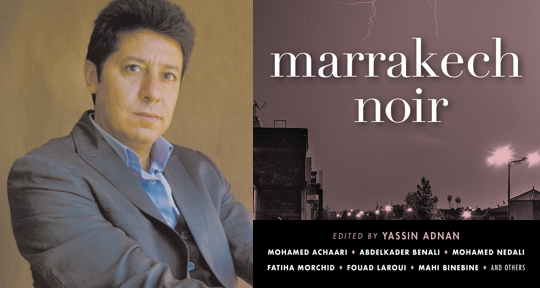

Marrakech Noir, collection edited by Yassin Adnan, translated from the Arabic, French, and Dutch by various, Akashic Books

With the twisting, winding small alleys in el-Medina, the bustling Jemaa el-Fna, a main square and marketplace, with its storytellers and performers, and the endless souks frequented by tourists and locals alike, Marrakech is the perfect environment for myths, legends, and stories. Seeing a rather large population increase over the past two decades as villagers and immigrants move to the city for opportunities, as well as an influx of tourists come to explore the tanneries, cuisine, and find a bit of paradise, the Red City contains a diverse landscape unlike any other in the world. Storytellers, like al-Sharqawi in “The Mummy in the Pasha’s House,” control the city’s reputation, and they can even “incorporate [a story] into the city’s very soil, till it became a part of its reddish clay or the dark green of its palm trees.” This phenomenon is notable throughout Marrakech Noir as each story, despite being written in the noir style, doesn’t reflect a noir city, but the noir that can exist in its occupants.

Marrakech Noir joins Akashic Books’s Noir Series, a series of anthologies of dark short stories set in different neighborhoods and locations around the world. This exploration of Marrakech includes stories by Fouad Laroui, Fatiha Morchid, Halima Zine El Abidine, Mohamed Zouhair, and more translated from Arabic, French, and Dutch, showcasing not only the linguistic diversity of the city but also the cultural and societal differences found within Marrakech’s meandering back alleys and main thoroughfares. But, as editor Yassin Adnan notes in the introduction: “Despite their variety, these stories remain rooted on Moroccan soil . . . ” which provides readers with new insight into a city with ever-increasing global popularity. The noir genre, while an odd literary form to use to boast about a city, manages to emerge in most stories in the anthology. The authors, however, make a conscious effort to divert the noir from the city itself and place it within the mélange of people of the city. Adnan describes the Marrekechi’s desire to tell stories with a lot of pizazz and spice; however, noir is a genre that doesn’t work as “the Marrekechi impulse is to always remain joyful.” Fortunately, that impulse was placed aside, allowing the noir to seep into the work for some powerful moments in the diverse cityscape.

Jemaa el-Fna unites practically every story as its importance in the city draws performers, local guides, tourists, and locals. Whether there to make a spectacle or simply sit in a café and witness one, everyone passes through this square. It’s in this square that Abu Qatadah in “An E-mail from the Sky,” after receiving an email from the heavens, shouts in religious fanaticism and awaits his escort to Paradise. Although not present in the square with the other onlookers, Rahal and his entire cybercafé watch as Abu Qatadah terrorizes tourists and is taken away by the police. In the same square in a different story, “A Person Fit for Murder,” Guillaume, a Frenchman who comes to Morocco to escape the monotony of France, is picked up by a young Moroccan boy who’ll fulfill his fantasies and eventually murder him. It’s also where Yusuf in “Mama Aicha” goes to gift a precious purple silk to the eponymous character and visit his former comrade, Aziz, with whom he joined in revolutionary thought and action until Aziz’s arrest.