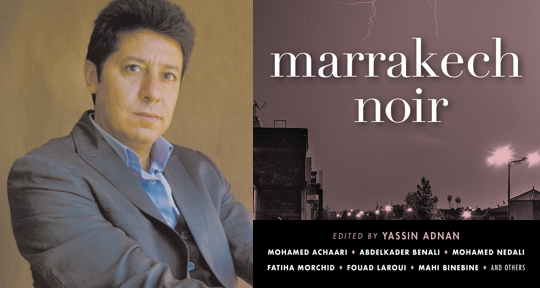

Marrakech Noir, collection edited by Yassin Adnan, translated from the Arabic, French, and Dutch by various, Akashic Books

With the twisting, winding small alleys in el-Medina, the bustling Jemaa el-Fna, a main square and marketplace, with its storytellers and performers, and the endless souks frequented by tourists and locals alike, Marrakech is the perfect environment for myths, legends, and stories. Seeing a rather large population increase over the past two decades as villagers and immigrants move to the city for opportunities, as well as an influx of tourists come to explore the tanneries, cuisine, and find a bit of paradise, the Red City contains a diverse landscape unlike any other in the world. Storytellers, like al-Sharqawi in “The Mummy in the Pasha’s House,” control the city’s reputation, and they can even “incorporate [a story] into the city’s very soil, till it became a part of its reddish clay or the dark green of its palm trees.” This phenomenon is notable throughout Marrakech Noir as each story, despite being written in the noir style, doesn’t reflect a noir city, but the noir that can exist in its occupants.

Marrakech Noir joins Akashic Books’s Noir Series, a series of anthologies of dark short stories set in different neighborhoods and locations around the world. This exploration of Marrakech includes stories by Fouad Laroui, Fatiha Morchid, Halima Zine El Abidine, Mohamed Zouhair, and more translated from Arabic, French, and Dutch, showcasing not only the linguistic diversity of the city but also the cultural and societal differences found within Marrakech’s meandering back alleys and main thoroughfares. But, as editor Yassin Adnan notes in the introduction: “Despite their variety, these stories remain rooted on Moroccan soil . . . ” which provides readers with new insight into a city with ever-increasing global popularity. The noir genre, while an odd literary form to use to boast about a city, manages to emerge in most stories in the anthology. The authors, however, make a conscious effort to divert the noir from the city itself and place it within the mélange of people of the city. Adnan describes the Marrekechi’s desire to tell stories with a lot of pizazz and spice; however, noir is a genre that doesn’t work as “the Marrekechi impulse is to always remain joyful.” Fortunately, that impulse was placed aside, allowing the noir to seep into the work for some powerful moments in the diverse cityscape.

Jemaa el-Fna unites practically every story as its importance in the city draws performers, local guides, tourists, and locals. Whether there to make a spectacle or simply sit in a café and witness one, everyone passes through this square. It’s in this square that Abu Qatadah in “An E-mail from the Sky,” after receiving an email from the heavens, shouts in religious fanaticism and awaits his escort to Paradise. Although not present in the square with the other onlookers, Rahal and his entire cybercafé watch as Abu Qatadah terrorizes tourists and is taken away by the police. In the same square in a different story, “A Person Fit for Murder,” Guillaume, a Frenchman who comes to Morocco to escape the monotony of France, is picked up by a young Moroccan boy who’ll fulfill his fantasies and eventually murder him. It’s also where Yusuf in “Mama Aicha” goes to gift a precious purple silk to the eponymous character and visit his former comrade, Aziz, with whom he joined in revolutionary thought and action until Aziz’s arrest.

Beyond this main square, the anthology offers a glimpse into other areas in Marrakech. Dar el-Basha in “The Mummy in the Pasha’s house,” is where a mummy is unearthed in an old palace that is now owned by a French couple. Amerchich, the asylum in “A Twisted Soul,” is where a student’s life changes as she speaks to a patient, Alice, and discovers an intellectual, elegant person with a rough past. But the authors don’t just simply paint an image of Marrakech and its neighborhoods. Readers are granted an insider perspective on slang and local flair, such as when you learn that: “Amerchich was the kind of insult you hurled at someone to accuse them of both foolishness and insanity . . . ” The works function as a guide, highlighting locations, local slang, and the every-day life found within the city limits.

Thanks to all of this diversity and difference found in just one place, Marrakech supplies everyone with what they’re looking for. The work, as a whole, does a stellar job at showcasing the city’s importance, influence, and cultures. Just like the authors and characters in the work, the translators of the stories, including Roger Allen, Anna Ziajka Stanton, Terry Ezra, Katie Shireen Assef, and more, bring different styles and flairs to English. There is a lot of wordplay and terms associated specifically to a cultural context or the city itself, which required the translators to navigate and find ways in which to create a similar impact without harming the narrative. While the repetition of the words can at times be monotonous, readers are provided with linguistic variations and an insight into Marrakech’s linguistic diversity through the translations, allowing them to add another level of discovery to the Red City.

An example of this can be found in Derkaoui’s “A Way to Mecca” when Hmad describes playing house with the girls as a little boy: “ . . . how to make zamita from ground pearl barley. Sometimes he made the zamita from wari, which was a thorny plant that sprouted seeds; it was then made into flour.” Jennifer Pineo-Dunn transliterates the Arabic words throughout the text and offsets them in italics to aid readers identification of non-English words. Then, Pineo-Dunn gives essential information of what “zamita” and “wari” are without disrupting the flow of the narrative and the text. This occurs later on in the narrative, but in a different way: “‘We go to the mosque now and alcohol is haram.’ Ibrahim was already beginning to feel tipsy ‘It’s not forbidden! . . . ’” In this case, Pineo-Dunn transliterates the first case of “haram,” but instead of repeating the word when Ibrahim explains that in fact, it is not “haram,” she changes it to translate the meaning of the word, thus instructing the reader on an Islamic principal without causing any disruption whatsoever to the narrative.

From themes of religion, revolution, and finding one’s way, the authors also provide a hefty sampling of the diverse groups of people present within the city. For Moroccans, the city has a divide of Marrekechi, born and bred, and “the others,” which just refers to any Moroccan who moved to Marrakech from another city or village. Most stories involve tourists—typically French ones—that venture to the city for an escape, or that settle in the city, hoping to have access to the red paradise all year long. Their lives often mingle with the locals whether for prostitution, entertainment, or friendship. Tourists and European foreigners are a type of currency that allows the city to run, providing income for guides, shop owners, and restaurateurs; however, they’re not presented in a negative light, but rather are viewed as essential to maintain the city and its culture. The tourists are joined by immigrants from Africa who’re often en route to Europe yet remain in the city, captivated by the environment and grateful for the opportunities provided.

Each story naturally hosts two languages—the original language is thankfully never fully replaced by English—more often than not, at least one more language is referenced, underlining the various groups present in Marrakech and their communication in various languages. “‘ . . . it’s like something out of Claude Gellée, dit le Lorrain!’” and “‘But I’ve never seen zellige tile on a wall. . . . ’” can be found on just one page in Fouad Laroui’s “The Mysterious Painting,” the first being pronounced by a French tourist and the latter by a Marrakechi police officer. This creates an interesting linguistic challenge for the translator, Katie Shireen Assef, who navigates three languages and cultures within one text. In fact, the linguistic confusion that can be found in such a multilingual place is referenced in that story as well: “‘ . . . You’ve still got to work on your pronunciation, though,’ the chief teased. ‘It’s âmes not ânes . . . a matter of souls, not donkeys. . . . ’” In most cases, the expressions and words are explained by adding an English word that provides some context, such as tile after zellige. The translators never leave the reader linguistically lost. What should be noted, however, with these examples is that a slight confusion when reading a word like “dit,” a French word left untranslated that holds little to no importance when understanding the story, actually provides the reader with the feeling of Driss, the person who confused donkeys and souls in the story, and many other people in Marrakech who communicate in a variety of dialects, languages, and gestures.

If I were to pull out just one story that exemplifies this anthology, Taha Adnan’s story, “Black Love,” translated by Ghayde Ghraowi, perfectly combines every aspect that makes this collection a must-read and an accurate representation of urban life in Marrakech. A young Morrocan girl, Noura’s relationship with her first love, Bilal, an immigrant from sub-Saharan Africa, ends and she turns to Issoufou, a Senegalese man trying to start a life in Morocco as a refugee. Noura’s mother objected to Bilal (causing the end of Bilal and Noura’s relationship) and objects to Issoufou (to whom Noura turns after Bilal), but luckily for Noura, a new family law allows her to marry according to her own will, so she is able to elope. The racial dynamics at hand in northern Africa, however, caused a rift between Bilal and Noura as her mother’s idea of a marriage between a Moroccan and an African is unheard of and unacceptable. Bilal could get over his anger, but never the racial slurs thrown at him by a woman whom he respected, throwing Noura into Issoufou’s open arms. Adding a bit of urban history to this tour of Hay Saada (literally meaning “Happiness Neighborhood”), the narrator explains that the neighborhood is relatively modern, developed fast, and offered affordable housing, which attracted all of these groups to the area, providing the author with a perfect backdrop for this familial drama. Readers are given a sneak peek into a neighborhood in Marrakech: its history and development, its diversity in races and religion, its many languages spoken and heard every day.

Additionally, Taha Adnan’s style and narrative structure causes the reader to empathize with Noura and hope that she finds happiness, ultimately leaving the reader feeling depressed when, to her and our surprise, her new life turns out to be a lie. Issoufou not only lied about what he’s doing in Morocco, but the police shock the other characters by revealing his real identity, the swindler and international criminal, Mamadou Alseeka. Finally, the story also reflects the Marrakechi idea of “noir.” The protagonist, while Marrakechi, is victimized by a Senegalese migrant to the city, placing the culpability associated with the noir away from Marrakech entirely. As with most of the stories in the collection, an area of Marrakech is showcased to the reader with just a bit of noir in the form of a scandal poking through here and there. Finally, Ghraowi’s translation does a wonderful job in relaying the text in beautiful English prose and not getting lost in typically long Arabic phrases, which often lead to run-ons in English if not met with great care. Fortunately, it does this without losing the flow and momentum often present in Arabic prose, pushing and exciting the narrative.

Marrakech Noir will send its readers to the Red City to not only explore its charms and heritage, but also to acquaint them with the diverse and lively ways of life that dwell within the city limits. Although not every piece of writing exhibits a perfect example of the noir genre or even of prose, each piece promises a different insight and perspective on Marrekechi society, expanding the reader to be included in the city’s culture, even if just for a moment. Navigating all of this difference creates an interesting challenge to translators, yet each piece reads in a fluent English that expands the reader’s world with its linguistic and cultural diversity. Whether you’ve been to Marrakech or not, this anthology promises to take you there.

Clayton McKee is currently working on a Ph. D. in Comparative Literature at the University of California, Los Angeles. He works as a copy editor for Asymptote and as an outreach coordinator for Trafika Europe. He has translated various excerpts for Trafika Europe and is currently working on his first book-length translation.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: