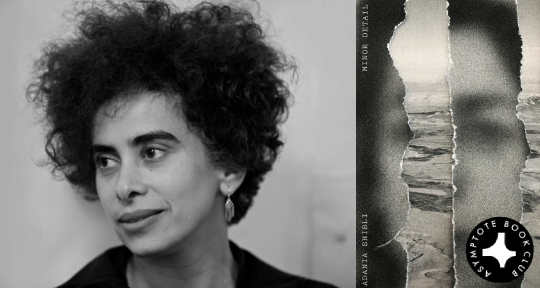

After the shameful decision to cancel Palestinian writer Adania Shibli’s LiBeraturpreis award ceremony at the 2023 Frankfurt Book Fair, everyone in the Global North flocked to read Minor Detail (translated into English by Elisabeth Jaquette), as thousands of writers, intellectuals, editors, and others in the literary ecosystem rightly condemned the cancellation. It was a symptom not only of Europe’s routine silencing of Palestinian voices but, more perniciously, of Germany’s particular brand of virulent anti-antisemitism, its Holocaust memory culture metastasised into a total interdiction on critiques of Israel.

Adania Shibli cites Samira Azzam—a writer whose seemingly unthreatening short stories describing everyday life in Palestine managed to pass the censorship bureau’s checks—as a formative influence. Azzam “contributed to shaping my consciousness regarding Palestine as no other text I have ever read has done”, Shibli writes, for it cultivated in her “a deep yearning for all that had been, including the normal, the banal, and the tragic”. For many of us, grappling with what solidarity and hope can mean in the light of Israel’s ongoing genocidal violence against Gaza, Minor Detail might be such an essential touchstone. How might we (re)read Shibli’s work today, not only as a prescient source of information about Palestine but also as a text that theorises and maps its own aesthetic possibility? With what voice does it continue to address us, reverberating through silence and the distortions of language?

One day, a splotch of black ink bloomed on my well-thumbed copy of Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail. I didn’t know where it came from. The blemish, to my consternation, appeared in the light-grey region of the cover, which depicts an undulating terrain. Misted waves, perhaps, or the volatile sands of a desert. Obsessed with keeping my books as pristine as possible, I took an alcohol swab and wiped the black dot right off.

The smudge was dispatched as swiftly as it had arrived. Days later, I noticed the alcohol had also dissolved the matte surface of the cover where I had rubbed it. A tiny glossy archipelago emerged, its lustre and its jagged edges visible only at an angle, under the light.

Now the sheen reproaches me for thinking I could make something disappear with no trace.

*

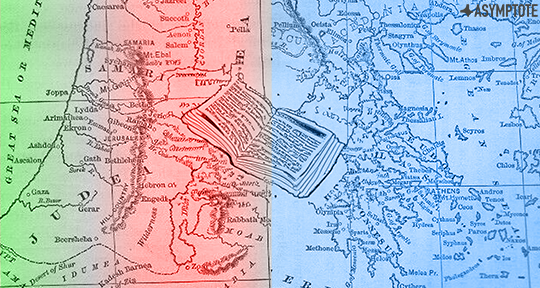

Desert / الصحراء

I want to juxtapose without asserting equivalence; the unnamed Israeli military commander in Minor Detail, too, believes in the seamlessness of disappearance. In the novel’s first half, he helms a Zionist platoon in a mission to conquer the Negev desert. This ruthless assertion of sovereignty takes place in 1949, a year after the traumatic Nakba dispossessed most Palestinians of their homeland. It is also a rearguard response to Egypt’s invasion of an Israeli kibbutz a year prior.

Charged with purging the land of “infiltrators”, the Zionist soldiers massacre a band of Arabs. They capture a Bedouin girl, humiliating, gang-raping, and murdering her. The horror of these bloodthirsty actions is continually evaded: “Then came the sound of heavy gunfire.” The narrative camera, as it were, turns its back on the moment of life’s desecration. Landscape itself seems to consent to these crimes. The desert, an aggressive mouth, collaborates in the erasure of evidence, each occasion with a different attitude: “languidly”, “greedily”, “steadily”, the sand sucks blood, moisture, substance into its depths. READ MORE…