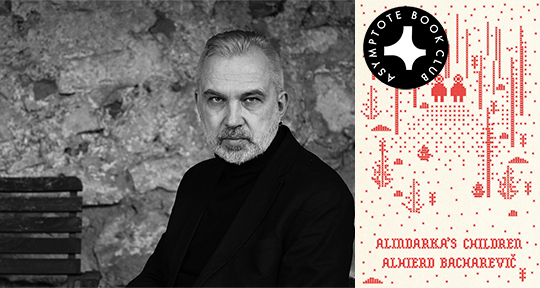

The translators of Alindarka’s Children, our May Book Club selection, had good reason to think of the text as an enormous challenge. Alherd Bacharevič’s subversive take on Hansel and Gretel is written in a musical tangle of two languages: Russian and Belarusian, addressing the conflict of Belarus’ languages in a powerful tale of intimidation, suppression, and postcolonial linguistics. Now released in a brilliant medley of English and Scots, the Anglophone edition adds new dynamism to the politics and cultures at work, immersing the reader in the complexities of what language tells and what it holds back. In the following transcription of a live interview, translators Jim Dingley and Petra Reid discuss their process, the pitfalls of classifying a language as “vulnerable”, and the creative potentials of dissonance.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Daljinder Johal (DJ): What were your first impressions of Alindarka’s Children? And what did you consider when making your respective decisions to work on its translation?

Jim Dingley (JD): Alindarka’s Children was published in 2014, I first read it in 2015, and my immediate reaction was: how on earth could anybody even begin to translate this? Then, when I was in Edinburgh with Petra, another Belarusian author began talking about this book with great enthusiasm. It suddenly occurred to me then that there is much being said about Scots being a language—distinct from English—and therefore a source of real national identity. With Scotland’s movement towards independence, it seemed to me that we could try to do something by contrasting English with Scots. I found working with Petra very rewarding as well, because she had an innate feeling for what we were trying to do, putting Scots up against “standard” English.

I think this adds a whole new dimension to the book, which is what any translator does when the process is not purely technical. You’re trying to get the sense of something. When you’re translating a book written in two languages, you can only get to the dynamic between them by introducing some realia from a country where another two languages are spoken. That’s why, in Alindarka’s Children, you feel as though you’re both in Scotland and Belarus at times.

Actually, I hope people experience some confusion with this book. It sounds very strange to say, but I think a lot of language is about dissimulation, confusion, leaving the reader to work it out at every stage.

Petra Reid (PR): Jim and I had very different experiences, because he speaks and writes Belarusian, while I have no knowledge of that language. So when I was reading the novel, I was reading Jim’s translation—that was the first time I’d heard of the novel or the author. In a way, I was reading it through Jim’s filter, and in that, it gained the context of a relationship between the English and the Belarusian.

I also came to it as a third party, as a Scot who doesn’t speak Scots—I was frank with everybody from the beginning, I warned them! I’ve got a strong accent, but I don’t speak Scots. The translation, and my work on it, is a personal explanation of my attitude towards Scots.

DJ: Could you expand on how that exploration went and what you got from it?

PR: What I like to do when I’m reading a translation is to try and imagine how the original sounds in my head, so even if you don’t have the exact vocabulary, you can approach the rhythm of it, and different nuances become available.

That’s what I found interesting about Jim’s translation; I was beginning to feel the Belarusian nuances through Jim. It was a two-way mirror, because Jim and I have our own dynamics in terms of how we speak English, and Jim has his own dynamic in terms of how he speaks Belarusian. It was a multidisciplinary, 3-D process, holding all these nuances in your head and trying to find a way to express that on the page. READ MORE…