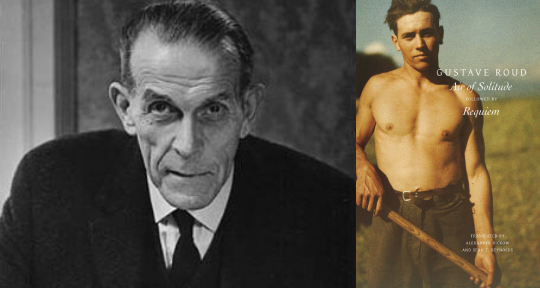

Air of Solitude and Requiem by Gustave Roud, translated from the French by Alexander Dickow and Sean T. Reynolds, Seagull Books, 2020

It is a question of the supreme instant when communion with the world is given to us, when the universe ceases to be a perfectly legible spectacle, entirely inane, to become an immense spray of messages, a concert of cries, songs, gestures ceaselessly beginning again, in which each being, each thing is at once sign and carrier of signs. The supreme instant also at which man feels his laughable inner royalty crumble, and trembles, and gives in to the calls coming from an undeniable elsewhere.

Once again the joy has fled with the change of season at the very moment we were about to come upon it.

Air of Solitude (Air de la solitude), the title of Gustave Roud’s most famous work is perfectly suited to the poet, who lived a secluded life isolated in Carrouge, his Swiss village in the Haut-Jorat. Moreover, it is crucial for the understanding of his poetry, which is rooted in these landscapes and customs, but often seen from an outside perspective. Considered one of Switzerland’s greatest poets, Roud’s work had a profound influence on the younger generation, the most famed of which is his mentee, prominent poet Philippe Jaccottet.

Roud published Air of Solitude in 1945 and Requiem, the second section of this two-part collection, in 1967. Whilst Air of Solitude expresses a celebration of—and nostalgia for—the inhabitants and landscapes of the Vaudois, Requiem displays Roud’s solitude through a personal quest to find a mystical fusion with nature and his beloved mother, who had already passed. This edition of his most important prose poems is now translated for the first time into English by Alexander Dickow and Sean T. Reynolds.

Air of Solitude, the first section, contains twenty poems, between which the poet inserts short, lyrical vignettes, recalling brief memories. The poems are strongly influenced by the changing seasons and the ritual, everyday work of the farmers; they move through the seasons, describing in immense detail the particular events and farming tasks of each month. On one level, the pace of these poems is the repetitiveness of this life: “the never-ending harvests.” Roud both celebrates this daily living but also detaches himself from it, seeking an absolute—a truth outside of time. From a narrative perspective, all of these rituals have passed and ended, and Roud speaks from a landscape of stillness, silence, and desertion, in a voice diffused with nostalgia. There is a sense that he must recreate these scenes conjured so minutely, and a word that courses throughout the poems is “lament”: a lament for what has been and is now lost.

In the second poem, “Presences at Port-des-Prés,” the narrator takes “the bench forever empty between two closed doors” by a barn at Port-des-Prés. We are immediately aware that he is moving between the real, the physical, and the imagined as “Port-des-Prés was quite near to where Time would soon go to lose its power . . .” Time exists as a greater force than the rote movement of clocks and calendars, and part of Roud’s talent is both his movement between them, and his endeavour to unite them.

Roud depicts rural, agricultural scenes so vividly that he seems to possess the meticulous eye of a realist landscape painter; his propensity for visuality is so overt that Antonio Rodriguez also notes in the foreword the importance of Roud’s work as a photographer on his aestheticism. His poems evoke all the senses, his landscapes orchestral, described in vivid detail with all their changing lights and colours. In this way, the “Air” of the title offers another musical meaning, as Roud creates his poems like symphonies that must embody equally all their different elements—fields, roads, mountains, labourers, clouds—to be understood only in their relation to each other:

Over there, in the nearly deserted orchards, the last apples are shaken down, these sweet little apples that will be mashed. The tree trembles, the hail of fruit hammers the grass with a sound recognizable among a thousand others, a brief beat of a muffled drum, and the slanting swarm of leaves hesitates and alights as a flock of birds.

Yet, the rhythm of the seasons and working the land is also crucial to the rhythm and formation of his own poetry:

Contrary to a train inscribing in the brain the naked rhythm in which some errant melody becomes mercilessly stuck, or to a stream that haunts you deliciously with a thousand mingled voices: reflections of phrases, reflux of songs, the lamentation of threshing lodges itself right away in the ear, once and for all, embeds itself in the mind, weaving a sort of neutral background against which stand out reveries, gazes, other sounds, even victorious ones over this basso continuo: up to this limpid, this aching birdsong.

This music contains layers of sound—voices of the past—which in turn contain the emotional response to such memories.

One of the figures consistently evoked in his memories is the desired male labourer Aimé. Writing as a repressed homosexual, Roud’s poems and landscapes are full of sexual energy. Man’s physicality is fused with the surrounding landscape and charged with eroticism:

The last clover falls, it’s a sliver of night that falls into the greater night; the scythe is an invisible whistling right up to the instant that Aimé lifts it upright and sharpens it: a hand of night caresses a pale steel crescent against the sky.

Roud frequently photographed young labourers and he brings the same level of detail in describing the landscape to describing the body. One poem especially, “Aimé’s Slumber,” portrays Aimé’s exhausted, sleeping body, now resting after “harvesting like a madman“:

He offered his hand to the night; the other sleeps next to the glass, freed from the scythe, freed from the razor-sharp straw of the bindings (those sheaves struggle under the knee like living bodies). He entered into his repose, it should be said, but that’s how the dead are spoken of, and this heart beats more forcefully than ours. The dark breast slowly rises and falls; a silver chain trembles there; the neckline is glimmering. Sometimes as in the sky a great, pale, light-bearing cloud might be traced, upon his opened lips flowers a species of smile.

Whilst Roud’s faithfulness to portraying the figures and routines of the Vaudois is crucial, he strikingly remains apart from the landscape: an outsider, who can only observe the labourers around him and conjure figures from his memory in his solitude. In “Letter,” he questions the origins of this love of solitude:

Where did I get this persistent love for great solitary farms lost amid their orchards and their prairies, closed universes, the sole places in the world where Sundays yet keep the taste of true Sundays, where one might sometimes find that thing more and more wrested from man: rest.

Roud inhabits “closed universes” for solitariness is associated with deep knowledge, observation, and with truth.

As he says in the title poem, “The absolute of solitude lies not in those high deserted places—it lies among men.” Those “high deserted places” are an “elsewhere” and a “mirage of solitary knowledge.” Roud’s poetry in many ways reconciles opposites, not least in this necessity for solitude amongst others. In contrast to Air of Solitude, Requiem (which Roud wrote over several decades) presents Roud’s solitude through his search for the dead mother. The poem is constructed as a dialogue in which (as in Air of Solitude) he attempts to find a meeting between memory and the present, and with the ephemeral and the eternal. He tells us, “My solitude is as perfect and pure as the snow” and that “The absolute of a solitude” of plants and men “draws them together to the point of exchange.” The “elsewhere” present in Air of Solitude here takes on greater importance, always menacing to prevent his discovery of the “ineffable.” In this later collection, we more clearly get the sense of a poet’s struggle in verse, turned in upon his doubts and anxieties. And yet, the poem is just as powerfully charged with his intense experiences of the world and his wilful desire to recapture them.

Despite his renown and legacy to Swiss poetry, Roud has not previously been translated into English. Furthermore, as noted in the foreword, assessment of his poetry has been biased and incomplete, positing him as just “a moral, sacrificial figure inspired above all by Novalis and Hölderlin.” These translations, on the contrary, skillfully render Roud’s elaborate poetic prose into English. The two sections work well together, both enhancing understanding of the other. This new collection is a powerful, superb translation from one of Switzerland’s greatest poets of the twentieth century.

Sarah Moore is a British editor and translator based in Paris. She is an Assistant Blog Editor at Asymptote journal and runs the monthly poetry events, “Poetry in the Library” at Shakespeare & Company. She is currently studying for a Masters in Comparative Literature at the Sorbonne University.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Reflections on the Daily: Jean Giono’s Occupation Journal

- When There’s No Wind, the Sounds of the Past are Audible Over the Danube

- Translation Tuesday: “Heimat Who Lives in a Box” by A.E. Sadeghipour