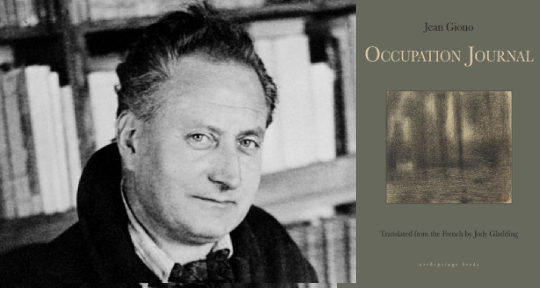

Occupation Journal by Jean Giono, translated from the French by Jody Gladding, Archipelago Books, 2020

This is not a journal. It’s simply a tool of the trade. My life is not completely depicted. Nor would I want it to be. As I’ve said, here I practise scales, I break up my sentences, I try to stick as closely as possible to the truth. But sometimes events are so rich with drama or pathos . . . that practising scales—my scales— isn’t sufficient and I have to invent. For me, anyway, expressing truths of this order is impossible without inventing. Moreover, it’s to be able to express them simply that I force myself to do this daily work.

—Jean Giono, “December 25, Christmas”

In his own words, this book is an exercise: a series of attempts to train himself in writing, for when his “trade” is truly called upon. His goal? Simplicity and truth. Yet, reading this work in 2020, now available for the first time in English and translated by Jody Gladding, it is so much more than a mere exercise. Jean Giono’s Occupation Journal is a fascinating record of life under Nazi occupation in France, and an insight into the daily reading and writing practices of a dedicated author. Written between September 1943 and September 1944 whilst living in the town of Manosque in the south of France, it was only published in French in 1995 (by Gallimard, as Journal de l’Occupation). The diary entries are a fascinating historical record as well as immensely clever insights into the presence and importance of literature in a writer’s life.

By the time he began Occupation Journal, Giono was already a well-known writer, with over ten works published, including his famous “Pan trilogy.” He was also equally famous for his pacifism. Having been called up to fight on the frontline in WW1, Giono would never forget the horrors of his experience, and the resulting principles influence all of his early work. This journal, therefore, comes at a crucial time in his development; the majority of his work published after the war left behind pacifism, whose failure he witnessed in the coming of a second war, and adopted a greater pessimism with regards to human nature. Certain writers, including Stendhal and Balzac, also heavily impacted his later writing. This journal is a key into discovering this period of transition—a period so evidently crucial in the development of his thinking that its importance cannot be underestimated.

The infusion of literature into his daily living is remarkable. Giono notes profusely what he is reading, what he intends to read, and his reflections on what he has read. His reading is structured and often consists of long classics: Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma, Balzac, Homer, Virgil. It’s almost enviable in its attention to detail and its scope—”I’ve read all of Proust carefully ten times”! Fascinatingly, he often views literature as a model, a possibility of this world, and he judges the world by the standards of those encountered in fiction. He views “nobility” and “grandeur,” for example, in terms of Lancelot and Don Quixote and applies this to war taking place in the “modern, mechanical world,” where, of course, society falls short:

But the quest for the Grail made the knights-errant gallop in a straight line. Even Don Quixote walks straight. Today it seems as though the Grail has shattered and they are chasing all the scattered bits of it in every direction.

Similarly, discussing the father of a potter who encourages his daughter’s work whilst simultaneously practising an occupation with an opposed goal (“Industry and the Commune”), Giono laments that: “With this category of the damned, the only relationships possible anymore are those of Dante.”

Additionally, Giono astutely considers the changing function of art and his personal vision of art. He makes much of the end of romanticism and, alongside this, the loss of the “individual.” Renowned for his concise style and diverse imagery, Giono is concerned with “truth” in art and often references film adaptations and the artwork of Vincent Van Gogh to explain his theories. Marcel Pagnol, an equally renowned writer and filmmaker also from the South, had already worked extensively with Giono and adapted four of his works into films. Throughout this journal, Giono considers how certain texts or scenes could be best adapted into moving images—especially Sartre’s Nausea—and how the problems encountered when trying to express the truth through this medium differ from others (e.g. representation of colour). Similarly, he extolls Van Gogh for his ability, not to “establish the truth,” but the “sensual truth of relationships.” It is an artist’s subjectivity that interested Giono, and that can ultimately allow for true artistic rendering: “It is the cypress + Van Gogh and the wheat field + Van Gogh. The mark. To leave his mark.”

His artistic vision was closely bound to the political climate, and he asserts that there “is no art of war.” As the journal progresses, the increasing aerial combat, assassinations, and approaching Gestapo lend a much darker tone to his writing; Giono’s pessimism and his fear for the world’s future are evident. For him, nations have reverted to a former mindset, and the future appears darker still: “As this war grows old, nations rediscover their original natures. France today is just as spineless as during the Hundred Years War.” And we see just how greatly Giono holds himself to ideals:

I regret the death of heroism pure and simple. It was the highest poetry man could attain. And modern man is going to die from a poetry hemorrhage.

Yet, despite the serious artistic and political reflections that are the core of this journal, in some ways, this is also just the diary of an ordinary (although astonishingly observant) man. Giono worries about money, he listens to his neighbours’ stories, he follows the progress of his children, he comforts them when they are frightened, he comments on the weather. It’s even extremely funny at times. All the while, it remains an exercise in writing and, even when commenting upon these trivialities, Giono has a unique, honest, and powerful style. Take, for example, this brief entry from November 17:

Sylvie is studying history. Her mother has her recite her lesson. What is a border? Sylvie: It’s a line where there’s an enemy on either side.

Or this entry from October 22, one of many exquisitely precise descriptions of the landscape and season:

The wind has been from the south for several days. Rarely have I seen the clouds as beautiful as the ones now rising. A moment ago, the east was masked by an enormous black band and the light came from the west in three long straw-colored streaks that reversed all the shadows. Then as the wind shifted everything went back to normal.

For of course, this is the journal of an established writer, who, even within these pages, grapples between his own identity and the “legend” of Jean Giono. He is acutely self-aware, humble, and often self-demeaning:

My shyness, which I’m constantly suppressing, robs me of all naturalness and simplicity. And being so patient, so stubborn, so pigheaded about following through with my plans, so faithful to my family ties, I have neither patience nor fidelity for the ‘ordinary’ and I withdraw as soon as I’m hurt. And that’s immediately.

Giono, who was arrested on September 8, 1944 and imprisoned for five months for collaborating with the enemy (although no charges were ever brought), knew that his character and his writing were under scrutiny. On March 17, he records “attacks against me in Les lettres françaises: I have no talent and I attract a following of cowards: lecherous viper.” On January 20, he asks himself, “Couldn’t being completely genuine serve as a kind of self-defense against my legend?” Even as he confesses to certain aspects of his character, we also begin to detect his essential qualities: a generous, dedicated, intelligent writer, totally committed to representing the landscape, the people, and the times that he knows so well.

Published in April, this English translation has unintentionally coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic, available to English-speaking readers for the first time during worldwide lockdowns. To a timely effect, many of Giono’s reflections also tackle the problem of isolation, of drawing upon inner resources, and of the consolation of literature: “To forget my pain, yesterday and this morning I quickly reread Louis Chadourne’s Le Maître du navire . . .” In all, the journals in their entirety compose a captivating account of a sensitive, dedicated writer’s quotidian life, and an insight into how he faced both the exterior and interior struggles of his time.

Sarah Moore is a British editor and translator based in Paris. She is an Assistant Blog Editor at Asymptote journal and runs the monthly poetry events, “Poetry in the Library” at Shakespeare & Company. She is currently studying for a Masters in Comparative Literature at the Sorbonne University.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: