A contemporary fable for the linguistic and cultural conflicts of post-Soviet Belarus, wherein the Belarusian language is at risk of being overwhelmed by the dominant Russian, Alherd Bakharevich’s Alindarka’s Children is a poignant and disturbing look into the myriad consequences of language suppression. Translated into both English and Scots, this multilingual novel is a vital testament to both the necessities and moral ambiguities of preservation, and a fascinating investigation of the intricate networks between expression and communication, adulthood and childhood, the public and the private.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

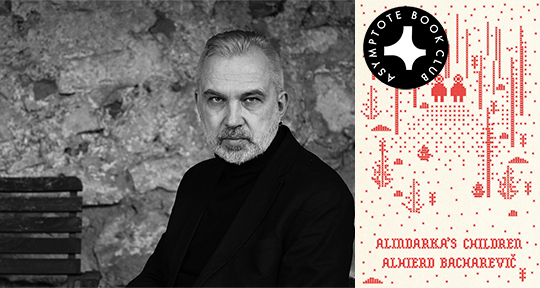

Alindarka’s Children by Alherd Bacharevič, translated from the Belarusian by Petra Reid and Jim Dingley, New Directions, 2022

Alindarka’s Children is Alherd Bakharevich’s clever reworking of a classic parable, using a simple Hansel and Gretel-like premise to grapple with real-life tensions between language and power in Belarus. Despite being written from the perspective of children, the novel plumbs deeply into the subtle darknesses and psychologies of Belarusian society. The novel begins with Alicia and her brother Avi, interned in a forested camp where children are trained to forget their language through a malefic system. The two are rescued by their proud and defiant father, but eventually slip away on an adventure of their own. As they explore the woods, encountering a series of memorable characters—interpreted from the original fairy tale and its confectionary-packet house—we are led to explore a world of anxiety and obsession, within which the duo must fend for themselves to survive.

Set in Belarus, the novel’s original Belarusian and Russian is brilliantly translated into both Scots and English, with colloquial Belarusian rendered into the former, and the main body of the book written in the latter. The dominant state-approved language, of which the camp is desperately trying to instill, is ‘the Lingo’—one can presume that it stands for Russian. ‘The Leid,’ or the Belarusian language, is left to slowly slip from collective memory, with Father attempting to impede its eradication by secretly speaking it to Alicia—or really ‘Sia.’ As a result, she remains silent at school, having been taught at home that the Lingo, too, is a forbidden language.

The constant sense of threat pervading the text casts a sinister air, and the reader is urged to share the same mistrust of others as Father. Even as we begin the novel with Alicia and Avi’s entrapment and escape from the camp, we experience the same persistent anxiety over its ruling figures: the Doctor and an intelligent teacher, Miss Edwardson, who have the state-sanctioned authority to separate families and punish linguistic dissent. The family’s unnamed and unidentified neighbours are also far from expressing any solidarity, as they eye the novel’s father-daughter relationship with extreme distaste and suspicion. In a telling passage, Father reflects:

To them, that is what a real maniac, family rapist and freak must look like. They knew, they could sense with that blasted tribal intuition of theirs that something was not quite right there.

And they were right.

If only they knew what it was that he and Alicia did together when they were at home.

Talking together, singing, playing word games, reading—isn’t this just the most terrible kind of perversion? No, it isn’t, provided it’s all done in the right language.

Whereas the state uses subtle but unnerving mental and political manipulations as their most obvious tools of suppression, this also engenders the constant physical threat of the mob’s inevitable violence. The cruelties, initiated by a reason as simple as speaking your own language, are visceral, and the isolation of this family heightens the challenges of trying to preserve the language. The narrative shifts back and forth in time, examining various perspectives—including those of Alicia, Father, and the Doctor—to show their individual, pervasive concerns over language, constant to the extent of obsession. Whereas there is an obvious, overwhelming disgust for the ‘wretched’ Leid throughout the nation, the Lingo is described as ‘pure’—but also ‘poison’:

It seeped into all the pores of the town, it was spoken by all the seasons of the year: the one right language, the one pure language, the one great language, the only healthy language.

While Father, Alicia, and Avi have arguably more natural reasons to obsess over their native language, the Doctor has an unhealthy, almost quasi-sexual fixation. Acquiring various languages himself and running the camp, he theorises on a biological effect of the Leid on the body and pursues this supposed dysfunction with single-minded determination. Even his own nurse is the victim of his humiliation. After she accidentally asks, in Leid:

“D’ye whant a nice wee cup o tea?” asked the assistant. “Likes o ah eyways make fur ye?”

She is then made to say it again, in Lingo, thirteen times. It soon becomes clear that this occupation is far more than a simple job for the Doctor, as he reflects:

She looked at him so helplessly that the Doctor began to feel disgust. The only thing that marks the difference between her and an animal is her language, something that was gifted to her by some caprice of nature. A language with a capital letter. A Lingo great and mighty, a hope and bulwark. What does she need it for? How has she deserved it? How can this creature have possibly deserved such a gift—a gift that she mangles. Every day she mangles it, she wrecks it because she is incapable of using it correctly. There is so much injustice in the world, and only doctors can put it right. Not politicians, not artists, not money. Only doctors.

Clearly, it is not solely the family at the centre of the tale who suffers under this oppression and tension. Empowered both by the presupposed purity of Lingo and the authority given by its title, language is constantly positioned as a tool of both repression and resistance. Lyrical or descriptive passages, then, are sparse in the novel, being largely devoted to only the nature of the forest or of certain women, including Father’s new companion.

His face lit up as they came nearer, just as though the forest had slowly parted its crown of treetops. A young woman with short yellow hair

Yellow hair, beyond compare,

Comes trinklin’ doon her swanlike neck,

An’ her twa eyes like stars in skies,

Would keep a sinking ship frae wreck

Most interestingly, the author and translators are using two languages, English and Scots, as a tool to further the themes of the book. With dialogue and thoughts written in Scots, a certain amount of time is needed to shift between the languages on each page, supplemented by definitions and a glossary of terms in Scots. Nevertheless, it has the powerful effect of allowing us to sympathise further with our Leid-speaking characters, presuming that one is likely to feel more at ease with the dominant English of the translation. Still, scenes in the book manage to elicit this same sense of understanding for those who often tread the liminal space between languages. In an interaction between Father and the slippery Miss Edwardson, he describes how he manages his transition into the Lingo-speaking world outside of his own home:

Usually, after leaving Alicia by her school he would sit in his car and try once again to tune himself into the Lingo, to switch off within himself all the little lights and knobs of his native Leid, and that’s how it would be until the evening when Alicia and he once again crossed the threshold of their fortress and shut the door.

It’s made clear how difficult this juggle is; especially when Father is driven to anger by Miss Edwardson’s intrusive questioning, he speaks purely in the Leid:

Ye stealt it. Ye chored it frae ma wee lassie. Stealt, nae dout aboot it. Yon’s aw yir pedagogie: dippin yir digits intae some ither body’s pootch, intae thair saul, intae thair mooth.

The state and community’s vitriolic treatment of Father also elucidates and validates certain elements of the story that some may consider implausible. While history has shown us that the use of camps was frequent across colonisers, the true extent of human cruelty is often smudged out and glossed over by historical accounts, with the depth of this struggle left in silence. Alindarka’s Children is a striking example of a writer’s role as witness and archivist, shedding light on all the disparate fragments of a nation divided by its languages—arguably the only tool of unification.

Despite all that promotes the protection of the Belarusian language in the novel, it’s interesting to see the moments that question Alicia’s role in this struggle; in a greater sense, the text ruminates on the enforcing of any kind of politics in between generations. In a moving passage, Father is caught in a rare moment of doubt, looking at ‘children who could speak, who did not have to hide from anyone. It would be interesting to find out if this made them happy. Children who were born just like that, without a mission.’

In Alindarka’s Children, it’s difficult to come away with any absolute declaration of what a struggle for language is worth. As readers of a world literature journal, it’s easy to assume that preservation and activism is to always move towards a better world, but in following the story of a father who consciously chooses to overwhelm his own children with the obsessive tendencies of his dissent, Alindarka’s Children is fascinating in provoking a moment of doubt.

Daljinder Johal is an assistant managing editor at Asymptote, in addition to being Head of Community at Boundless Theatre. She works across production, marketing, journalism, and curation in addition to being a writer, to create joyful and thoughtful work that shares nuanced perspectives from voices often underrepresented in the arts and film industry. She has a particular passion for highlighting the creativity of regions outside of London primarily across theatre, film, festivals, and audio.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: