Decisions about the books we read are more important than ever in the outpouring of the Information Age, so for this month, we bring you three texts of learning, authenticity, and artistry. An Argentine novel that rescues silence, a Hungarian volume that engages the incomprehensible, and a collection of Russian poetics from a master of Moscow Conceptualism—these works accentuate the diverse revelations and immense endeavours of world literature.

Include Me Out by María Sonia Cristoff, translated from the Spanish by Katherine Silver, Transit Books, 2020

Reviewed by Daniel Persia, Editor-at-Large for Brazil

A mishap at an international conference prompts simultaneous interpreter Mara to change course in Include Me Out, by María Sonia Cristoff, translated from the Spanish by Katherine Silver. Mara, tired of the monotony of her everyday interpreting, designs an experiment: she will spend one year in silence, as a guard at a small provincial museum outside of Buenos Aires. It is a job that will allow her to interact with nothing but her chair, she thinks. A job that will allow for stillness, for time to plant in her garden, she hopes. But when an unwanted promotion forces Mara to assist the museum’s gregarious taxidermist as he restores two of Argentina’s heroic horses, Gato and Mancha, an experiment in silence quickly transforms into frustration over static noise. A careful and deliberate portrait, pointedly translated, Include Me Out paints a memorable, authentic cast that stays with us long after we have finished reading.

Cristoff’s novel revolves around two major axes: the first, a plot-driven narrative, carried primarily by Mara, her handyman friend, the taxidermist, and his wife; the second, a string of historical and literary passages that provide cultural context on Argentina, the museum, and Mara’s job. Right out of the gate, the reader is struck by Mara’s peculiarities and curiosities: “to remain silent is also a discipline of the body,” she writes, in her “manual of rhetoric.” Mara’s former occupation as an interpreter generates much of the philosophical core of the novel. “An interpreter can never, for any reason, remain silent,” Mara reveals—though they can “pop pills,” “strip naked in front of [a] colleague,” or even plan “a brilliant heist that remains a mystery to the police for centuries.” Simply put, Mara is a fascinating character, and the reader can’t help but want to get to know her more.

The secondary strand of the novel—a series of short, interspersed fragments titled “From the Notebook”—sometimes seems to interrupt the storytelling. That said, for every reader who skims over these sections, anxious to uncover more of Mara’s plan for retaliation, there is another who is completely absorbed, eager to learn about the Argentinian history that gives the novel its distinctive flair. The context is there, for those who want it, and the novel feels fuller because of it.

Silver’s translation is, without a doubt, elegant, faithful, and well-constructed. Perhaps one of the text’s hidden beauties becomes most apparent in translation—or when read by translators. At times, Cristoff writes about the “art” of taxidermy as if it were translation. Take the following passage, for instance:

While she watched him obsess over the perfect form, over attaining the original or even surpassing it, she couldn’t help but focus on everything that was thrown out during every taxidermy. The guts, the organs, the bones, the sinews, the fragments of skin. She stopped seeing them as what they were, and she started to see them as raw material, a strange type of material: something in constant oscillation between life and death.

In its notion of striving for perfection or “surpassing the original,” the passage invokes some of the most classic translation theories, from Walter Benjamin to Gregory Rabassa. “The guts, the organs, the bones, the sinews, the fragments of skin”—what a fascinating way to think about language itself, about words and the “raw material” of translation. Translators are, after all, working in constant oscillation, adding things in, taking things out, messing with the overall composition. Taxidermy becomes a new metaphor for restoration, reformulation, translation. And, as Mara enables us to see, silence is a necessary component of the art.

A curious tale unlike much of what is on the shelves today, Include Me Out is a refreshing reminder that good literature comes in various forms. Readers will find comfort and resolve in Silver’s masterful prose, even when the plot forces them to question the nature of work, relationships, and the noise of their everyday lives.

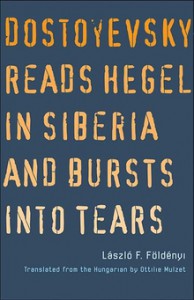

Dostoevsky Reads Hegel in Siberia and Bursts into Tears by László F. Földényi, translated from the Hungarian by Ottilie Mulzet, Yale University Press, 2020

Review by Barbara Halla, Assistant Editor

Given my amateur knowledge of Enlightenment history and philosophy, I was initially hesitant to review the work of an expert: László F. Földényi is a literary critic, professor, and chair of theory of art at the University of Theatre, Film, and Television in Budapest. Dostoevsky Reads Hegel in Siberia and Bursts into Tears is a collection of thirteen essays that testify to Földényi’s erudition and masterful grasp of two millennia of European intellectual history. But while the essays that make up this collection certainly showcase his credentials, they are never inscrutable. On the contrary: they all have an intimate quality that often makes them feel more like deeply personal meditations than simple academic endeavours. Földényi is not shy in granting them such a tone, especially when talking about inherently universal experiences like childhood fears or how art can move us beyond words. And it is precisely Földényi’s approachable style, as well as Ottilie Mulzet’s impeccable translation, that makes this collection easily accessible to scholars and casual readers alike.

Földényi manages to cover an impressive array of subjects: fear, sleep, the intimate relationship between happiness and melancholy, the externalization of our demons through history, and of course, the limitations of Hegel’s views on the latter. Yet despite this thematic breadth, Földényi consistently returns to one topic: the Enlightenment’s impact not just on Europe’s intellectual history but on our relationship to divinity, the metaphysical, and essentially our own mortality. He aims to explore how we humans have dealt, through art and literature, with the knowledge that some part of our identity and purpose will always elude mere reasoning. He uses the term atheistic religiosities to describe those experiences in “which human life is revealed as deeply embedded in a series of profound coherencies pointing well beyond the manufactured structures,” and argues that our propensity for such revelations has been undermined by the Enlightenment’s secularizing mission—its attempt to tame the metaphysical realm and establish that everything may be rationalized and understood by our senses.

Földényi is sympathetic to Enlightenment philosophers’ desire to pretend all is comprehensible. After all, he claims, there is something almost unbearable about the inscrutability of the cosmic order that we inhabit. But Földényi also contends that this successful, ongoing process of secularization has had unintended consequences: while we were once united in the knowledge of our mortality and ignorance, the selfish replacement of divinity with reason has broken our connection to the cosmos and each other. We were closer, he seems to suggest, when we knew how insignificant we were on our own and relied on religious experience and the idea of God to connect us with the universe at large.

This line of thought has a few limitations: while the author does speak of atheistic religiosities, he seems to imply that the best (and perhaps only) way for us to get in touch with our place in the cosmos is to acknowledge and submit to the existence of the divine. In addition, his interpretation of the Enlightenment’s legacy does not take into account the movement’s fraught, symbiotic relationship with Christianity; it appears to derive from Kant’s reason-based definition of the Enlightenment and ignores the views of other contemporary philosophers like Hume, who held a rather different opinion on the matter.

That being said, there is plenty to enjoy, learn, and be moved by in this collection. And I sympathize with Földényi: There is a certain beauty in religious texts, especially when they bear witness to our fraught relationship to each other and our place in the universe. Our sometimes unwilling attraction to religious interpretations, our yearning for some divine explication, is perfectly understandable, for as Földényi beautifully says, “[our] consciousness of our own mortality [has] doomed [us] from birth to [a] homesickness for the metaphysical.”

Soviet Texts by Dmitri Prigov, translated from Russian by Simon Schuchat and Ainsley Morse, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2020

Review by Andreea Scridon, Assistant Editor

Fewer of us have heard of Dmitri Prigov than we ought to have, what with his status as a “pop artist” in an anti-pop world. A sculptor by professional formation—something evident in the fact that his many books of poems and prose are constructed almost like modern art installations (clinical, sequential, both theoretical and intuitive, and necessarily concerned with making a statement)—Prigov was enormously prolific, a dissident and a founding member of Moscow Conceptualism. He is also, as his writing in Soviet Texts suggests, a figure capable of slipping through one’s fingers, eschewing the impulse for clear classification.

Writing as an independent reviewer, I’ll commit the indelicacy of being responsible for a point of contention: in the Translator’s Note, it is argued that “Prigov redefined the role of the poet away from the Romantic identity inhabited by poets like Brodsky.” In fact, what is interesting about this poet is not his departure from the Romantic tradition but rather his participation in it: what seems at first glance to be surreal nonsense and rubble quickly proves to be a unique flexibility of thought buttressed by stylistic verve and strength, and a premise for the poet’s experiments with the porous borders of time and space. Most of the selected works in Soviet Texts (a carefully and well-curated compendium of his work) represent a sustained interaction with his forerunners: he references his childhood, much like Tolstoy, and presents a veiled autobiography of sorts, like Bunin (though his is far less linear); Pushkin and Dostoevsky reappear as characters, as does the city of Moscow—this last concept is one that Prigov truly hammers home, writing in the urban tradition of countrymen like Bulgakov and Bely. He talks back to and with Russian poetry, asserting grand and almost universal intentions:

How beautiful my ancient Moscow

When she stands modestly reflecting

In the bluish waters of the gulfAnd reads the dreams of Ashurbanipal

And a hot wind blows in from the southCarrying the neighboring desert’s sands

Swirling through the streets of Moscow

While returning, time and time again, to a vision of Arcadia:

To pronounce the third letter he finds himself a little child clad in a white and blue sailor suit, roaming around an old-fashioned garden, wandering into an unfamiliar gazebo, in deep silence tracing a pale, thin little finger on the dusty marble parapet the outline of an unexpectedly emerging.

Prigov is, however, simultaneously a whimsical and humorous writer, at times hysterically funny: “I scored some chuck strips at the deli counter / And headed for home, coddling my bounty,” “Out came a filthy decrepit old bitch.” This translates well into English, conveying occasional hip-hop vibes:

But no, she was just random, and plus she was ugly

While me, I’m a poet, the pride of Russia, that’s me

Half the day wasted standing with strangers

But happiness lives with the likes of these bitches

It is in Housekeeping in particular that he turns tragedy into comedy, casting light and shadow on the whole affair of deprivation. This recurring theme is turned on its head in different ways, successfully demonstrating the true complexity of those living conditions in a clever way.

As is to be expected, much of the content is deliberately ironic, pastiching the wooden language of Soviet officials. Prigov further deliberately sanitizes matters by prefacing every book with a laconic manifesto called an “Advisory Note.” In this sense, this book is surely an interesting read for those interested in seeing the way multiple texts, perhaps in different forms (though Prigov is somewhat predictable in prose and a better poet for it) interact with each other conceptually. All of the collections are extremely taut on a notional level, and one that stands out in particular is Twenty Stories about Stalin, a list of anecdotes, almost formulated like aphorisms that purposefully falter, in which Stalin is flattened and caricaturized in a cartoon-like fashion, so that his infamous sociopathic tendencies become apparent. It is a very interesting text for us to read in an era that has produced films like Death of Stalin, Jojo Rabbit, The Real Chernobyl, and Look Who’s Back, and it isn’t difficult either to imagine how shocking such writing would have been at its time.

Hyperaware of this axis of distortion that communism represented, Prigov fundamentally seeks to discern the essentials of the often poignant Russian spirit:

Perhaps, only the faint cold shiver from her cool hands reaching for me by night in an alien land. Her hands reach closer, closer—perhaps to embrace me, or perhaps (again, at a distance, and in night’s delirium what doesn’t one imagine!) to seize me by the throat. Well, and what of it? It’s her right! And I would never deny being subject to her laws or desires. That’s just how it is. (“My Russia”)

I recommend Soviet Texts not only as an exceptionally translated book of Russian poetry and prose, but also as an original reminder of what liberty, and its antithesis, can both mean.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: