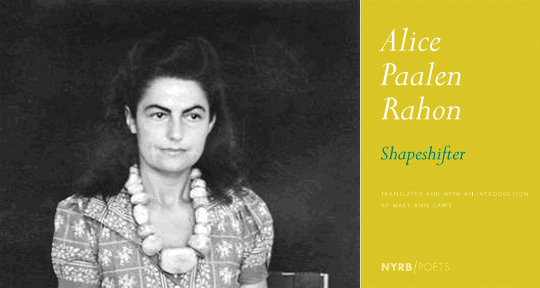

Shapeshifter by Alice Paalen Rahon, translated from the French by Mary Ann Caws, New York Review Books, 2021

Surrealism has left an indelible mark on our cultural imagination, a defining umbrella term for the experimental and the dreamlike, from poetry to imagery. Though a litany of artists come to mind when we think of surrealism—from its founder figures André Breton and Philippe Soupault to visual exponents such as Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, or René Magritte—the legacy, albeit impressive, remains overwhelmingly, and perhaps erroneously, masculine.

Some work has been done in recent years to revise that history—such as through new translations and a number of exhibitions for British-born Mexican artist Leonora Carrington. Now, translator and professor Mary Ann Caws has curated and translated the works of poet and painter Alice Paalen Rahon to further our reach towards the women of surrealism, in the volume Shapeshifter.

The visual arts have long dominated the conversation around surrealism, despite its origins as a literary term—coined first by poet and theorist Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917, then used in two manifestos in 1924, of which Breton’s has stood the longest and is now seen as definitive. Breton described Surrealism as “psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express—verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner—the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.” Though first staked in terms of the “written word,” the paintings of Dalí or Magritte may now serve, for many, as the first introduction to Surrealism. This domination of visuality in Surrealism has also affected Paalen Rahon’s legacy. Her artwork has long been appreciated in her adopted home of Mexico, celebrated with a large retrospective in 2009 at the country’s Museum of Modern Art. However, with the arrival of Shapeshifter, we can gain valuable insight into this remarkable poet who was one of the best of the Surrealists, despite the lack of wider recognition.

Even embarking upon a simple biography of Alice Paalen Rahon poses its own challenges and complications, implicating towards the mysterious and inventive nature of her work. In her own words, she was born in 1916 in Goulven, Brittany, but this was a biography of her own creation—Brittany was in fact a beloved holiday spot for the poet who was actually born twelve years prior in 1904, as Alice Marie Yvonne Philippot in Chenecey-Buillon in the Doubs. Her nom de plume is a combination of names: from her first husband, the Austrian painter Wolfgang Paalen, and, after their divorce, the addition of her mother’s maiden name, Rahon.

Paalen Rahon’s attempts to obscure her biography offer a peek at her inventive spirit, but other details are more transparent. As a teenager, she moved to Paris with her family, and would meet her husband in Corsica, marrying in 1934. On their return to Paris, they led a lively social life, mixing with artists from Joan Miró to Pablo Picasso—with whom Paalen Rahon would have a brief affair in 1936 (Caws provides us with poems that Picasso wrote to Paalen Rahon, along with a photo of the original handwritten lines, for those of us who indulge in literary drama). She then travelled to India with poet Valentine Penrose, who would become another of her lovers, and in 1939, with Hitler casting a long shadow over Europe, the Paalens travelled via the United States to Mexico, where Alice settled permanently.

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Paalen Rahon penned the vast majority of her collected poetic output—she would focus on her visual work in the decades that followed. It’s against the backdrop of these romantic and geographic meanderings that her poetics transpire.

The collection that opens the text, On Bare Earth, is a formidable emblem of Surrealist poetry; published by Éditions Surréalistes in 1936, it was prefaced by Yves Tanguy, and praised by Breton as a “talisman.” It’s difficult not to read the collection in a rush, swept along by the elemental force of the title. From the very beginning, we start to uncover a sort of visual alphabet, images and themes that mould Paalen Rahon’s poetry—beasts, skies, paths, light, stone.

Her unique approach is evident from the very first lines:

A woman once lovely

one day

took off her face

now her head was smooth

blind and deaf

sheltered from mirror traps

and looks of love

One critique commonly levelled at Surrealist poetry is its inherently gendered perspective, particularly when its best-known exponents are all men. In a poetic landscape where all is reduced to uncontrolled thoughts and first impressions, the rejection of the rational mind and the embrace of pure instinct, female bodies can feel like props in service of a pre-determined goal. However, Paalen Rahon opens her debut collection with a decidedly surreal image without any objectification, for in fact the surreal serves as protection from concerns of beauty (“mirror traps”) or romance—issues that continue to have an outsized effect on women and feminised people.

Mary Ann Caws’s insightful prologue describes Paalen Rahon’s painting style as akin to representational abstraction—a work that initially appears abstract, but in fact represents a scene through colour, shape, or texture. This also serves as a helpful analogy for Paalen Rahon’s poetic practice. The imagery is as vibrant as if it were painted:

The looks have changed their source

A bell

in the storm’s blue bronze

pursued to the wind’s zenith

by the lost horizon’s

white wing

While the first person rarely appears in the earlier poems of the collection, its occasional intrusions remind us of the poet’s eye, observing and capturing these visions and dreams.

As the collection develops, the first person tentatively emerges with increasing agency. There is a shift from the seeing “I,” the eye of the painter, the person who can be led—”Blind paths / draw my steps / away from here”—to a more active subject:

I cannot help you to flee this assembly-line fate

Even though the agency is stilted, lacking, oppressed somehow—”I can do almost nothing for you”—it marks a break in the collection for a more involved first-person subject.

Other breaks occur when the style shifts from free verse to prose poetry. Paalen Rahon’s visual praxis surfaces when our eye encounters a block of text that appears in a completely different shape to the previous poems—a visual marker that something has changed. It first occurs in “Seated on the pendulum,” a poem that incorporates some of the exoticising references and tropes that the Surrealists were known for—such as the somewhat generic allusions to “scarabs” and “pyramids.” Surrealist icons have been rightfully criticised for exoticisation and appropriation, in which the term “surreal” suddenly comes to mean a lack of legibility for the European artistic elites who, upon encountering American, African, or Asian cultures for the first time, intellectually conquer them by claiming them as a product of their subconscious. While this trajectory plays out in Paalen Rahon’s biography—such as her ‘discovery’ of Native American art and her time in an ashram in India—her references to other cultures are less overwrought than Breton’s, for example, who, barely two months into his stay in Mexico, described it as the “Surrealist place par excellence” and would characterise it as a “land of convulsive beauty.” For a movement that sought to suppress rationality and instead idealised instinct, there is no doubting the exoticising spirit of Breton’s remarks which were projected onto a ‘primitive’ nation—surely for them the opposite of a ‘rational’ post-Enlightenment France.

Paalen Rahon, in contrast, aims for sensitivity instead of simplification; in “Mdabouli you are a girl of this country,” the description of the country in question, Kenya, relies relatively little on stereotypes or tropes, and instead conjures the delights of travel, in another prose section:

In this country there is so much sky that at night you have to fold it a little at the edges especially if there is a wind

In Reclining Hourglass, the second, shorter collection from 1938, the themes of gender and travel return, more evolved and with greater poetic skill. In the collection’s brevity and economy, it highlights the deftness of Paalen Rahon’s poetic practice, matched in turn by Caws. The translation throughout keeps the openness and rich semantic resonances of the French—such as with the original title, Sablier couché. “Couché” evokes lying down, but also sleeping, and “reclining” is apt in its ability to describe both living beings and inanimate objects.

The opening of this second collection feels more personal, and more urgent:

No sleeping wind shall carry my head

no hand with the imprint of my cheek

no arm will hold me

In the coalesced imagery of the dove, its dress worn out from captivity, and the deserted woman, there is a sense of a yearning for freedom. This lineage continues through “Here is Orion the great man of the sky,” wherein freedom comes from being set afire, and in “From language speaking the heartbeats,” upon which we wonder if language might be the path, with the poetic subject evoking the “feminine voice.” She “open[s] the locks of the shadows,” and the collection ends with “Muttra,” named for Paalen Rahon’s time in India:

Breasts freed now you fly and sing

Her final collection makes explicit the connection between the animal and the poetic—1941’s Noir animal refers to a black pigment made from animal bones, cleverly translated as Bone black. There’s a lingering simultaneity here between her linguistic and visual practices, and the collection is thematically darker; beginning with “crowing cocks” and a particularly Biblical allusion to doom, the first poem ends simply with the word “death.” The Paalens left Europe in 1939 and Paalen Rahon would never live there again, and in light of that historical context, the signs of mortality feel appropriately weighty. In “The Supplicants,” the poet ends with the violent image of a “firetrap to burn up everything.”

The element of mercury is a recurring thread; in the poems’ titles, it is “snuffed,” “stoned.” And while this collection is replete with violent imagery—fire, death, lightning and thunder—”Native Mercury” suggests some glimmer of transformative potential, the mercury growing upwards and “fertilising space.”

We also get more evocations of the geographic, suggesting the power of travel for the Surrealists:

In the burrow of passive slumbers

avid geography

seeing the world

antidote antipode

The playful “antidote antipode” suggests the restorative nature of the “tour de monde.” This collection also includes the first poem dedicated to Paalen Rahon’s life in Mexico: “Pointed to like the stars.”

Paalen Rahon wore many hats throughout her life (quite literally, at one point—both designing hats and modelling them, in photographs taken by Man Ray). Poet, painter, milliner, model, artist—Paalen Rahon embodied the far-ranging imaginations of surrealist pursuit: a shapeshifter. Through this formidable work of curation and translation, we have been given the rare and special opportunity to glimpse her myriad forms.

Georgina Fooks is a writer and translator based in England, Director of Outreach at Asymptote and a poetry editor at the Oxford Review of Books. Her writing and translations have been published in Asymptote, Viceversa Magazine and Simone Revista. She is currently completing a master’s in Latin American literature, specialising in Argentine poetry.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: