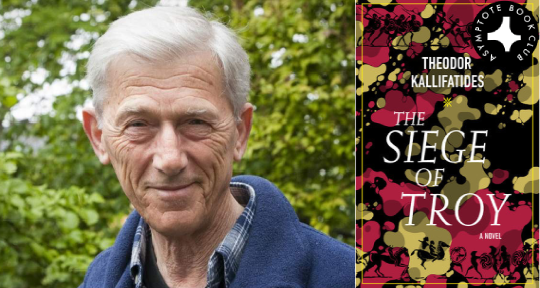

Contemporary writers have continually found original ways to tell enduring stories, as demonstrated masterfully in our September Book Club selection, The Siege of Troy by Theodor Kallifatides. By weaving the retelling of a classic myth with a World War II-era bildungsroman, this stirring novel simultaneously enlivens The Iliad while delivering a potent and poetic demonstration of war’s senselessness. Psychologically probing and structurally unique, The Siege of Troy is a thoroughly modern work that proves why we return again and again to timeless themes—there is always something new to be found there.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers in the US, the UK, and the EU. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page.

The Siege of Troy by Theodor Kallifatides, translated from the Swedish by Marlaine Delargy, Other Press, 2019

No matter how many stories we’ve heard about love, war, and growing up, they never fail to reach our hearts in the specificity of our own place and moment. This is the simple, poignant premise of Theodor Kallifatides’s The Siege of Troy, translated from the Swedish by Marlaine Delargy, which sets an adolescent boy’s coming-of-age story against a selective retelling of The Iliad.

A Greek immigrant to Sweden, Kallifatides grew up during the German occupation of Greece, and his nameless protagonist emerges sweetly and painfully into his early manhood under the same conditions. The war is nearing its end; though both the occupiers and the occupied are exhausted, tensions continue to surge and survival is far from guaranteed. During regular air raids, the protagonist’s teacher recites The Iliad from memory to her class while they all take shelter in a cave. READ MORE…