Going from a context in which Kevin O’Rourke’s translation of Yi Mun-yol’s Our Twisted Hero was the only visible sign of Korean fiction in English, and Brother Anthony of Taizé’s translations of Ko Un the only ready example of Korean poetry, the current popularity of Korean fiction and poetry in the English language market does seem to speak of the “Korean wave” prophesized by my Korean teachers. Dalkey Archive Press’s publication of twenty-five works of fiction, supported by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea, played a seminal role in this transformation. But just as important has been the interest of small presses, including Zephyr Press’s 2006 publication of Anxiety of Words: Contemporary Poetry by Korean Women, and the recent publications of Korean literature by Deep Vellum and Action Books. In the UK, Deborah Smith’s work as a translator and promoter of Korean literature, not only through translation but also through Tilted Axis Press, deserves special mention as well.

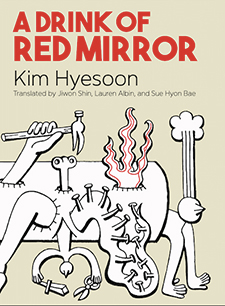

Kim Hyesoon’s A Drink of Red Mirror, published originally in Korean in 2004, appeared in English this year from Action Books. However, unlike almost all Kim translations in English, this book is not the work of Don Mee Choi, the translator who has almost single-handedly introduced contemporary Korean women poets to English-language readers. Rather, this book is a collaborative exercise by as many as eight translators. The afterwords, seemingly aimed at the translator-as-reader with an interest in the processes and pedagogies of translation, trace the complex process by which these English versions took shape, as well as some of Kim’s own ideas about translation. Fortunately, the effect of “translation by committee” is not visible across the book through deviations in style, tone, or voice.

Kim’s poetry is often said to be both feminist and experimental. In this collection we find many images of maternity, childbearing, childrearing, and male-female relations. These images are often gruesome, violent, full of hardship, and may conduce a critique of the place of women in Korean society; but the first sensible impact upon this reader is one of a protracted maternal nightmare, full of suffering:

The woman became pregnant

so her father yanked and stretched her lips (“Lady Yuhwa”)

There are days a baby pops out of a hole (“A Hole”)

the infant

who has just popped out of the mom’s belly just offscreen

has a rapid aging disease or something (“Baskin Robbins 31 University Road”)

When the rooms where babies are asleep shatter (“The Woman’s Baton”)

That thing

that ate away the cheek of my baby (“Detective Poem”)

Shiva’s wife’s ripped flesh

burns in the sun (“Cambodia”)

A rat goes in and out of her body

Gives birth and raises babies (“Scribbled Letter”)

the canes men break

when they hit women (“Deep Place”)

When copulation is over Ms. Photon eats her lover (“The Cultural Revolution Inside My Dream”)

To borrow entirely from European aesthetic history, we could say these are Surrealist Symbolist poems—sparse evocations of dreamspace that veer into nightmares where the self can attempt to mediate and lessen the institutionalized harms of the world. This poetry produces scenes not through the rational mind but through emotional or affective intelligence and imagery. Though it may be difficult to express through critical language (inherently rational) the attributes of affective imagery, to me the most moving poems are ones such as “Room 1306,” “Woman Trying To Become A Bird,” and “Eye Of A Typhoon,” that convey their emotional intelligence in part through very old poetic devices: anaphora and refrain.

“Room 1306” repeats the phrase “A nightmare is delivered.” It then uses this syntax—indefinite article, common noun, verb—repeatedly, building in a crescendo before ultimately winding up where it started: “A nightmare is delivered.” Reminiscent of the artist diaries of Kim Cheom-seon and her endless reimagining of herself as animals, “Woman Trying To Become A Bird” also prominently features anaphora, repeating a series of questions with the tag “Have you ever. . .” in order to lead the reader along an imaginative journey to becoming a bird. The most troubling poem in the collection, “Eye Of A Typhoon,” which somehow recalls the 2014 Sewol ferry tragedy, despite its original publication ten years before that unspeakable horror, starts with the speaker abandoning a child in front of a mental institution. It is hard for me, as a father, to read “a child with a crushed chest,” “a child whose lung at every breathing hole is filled with stones,” and so on in a series of devastating, violent, suffocating images.

Choi says that Kim’s work is the “most experimental” among contemporary Korean women’s poetry, and Jiyoon Lee has suggested it is partly because the “source poems mostly use no punctuation”. Yet, while there are some formal differences among her poems, the range doesn’t strike an English-language poetry reader as particularly experimental, given that punctuation (and capitalization) have long since been optional for English language poetry. Rather, we are better able to locate Kim’s experimentalism in her poetry’s tone and content—in the psychic landscape that unfolds in these poems. Dreams, nightmares, phantoms, and mirrors provide the conceptual frame for this psychic drama. Real-world events are difficult to discern. Proper nouns are few and far between, and their relative absence further dissociates the poems from a mimetic style and from social reality. The poetry is that of psychic recovery, in which speakers frequently feel trapped:

“Inside you there is another you” (“Face”)

“There must be a prison inside my body which fits me just so” (“Eurydice Trapped in Print”)

“Like a tomb there’s no emergency exit anywhere” (“My Panopticon, That Bird’s-Eye View”)

“There are times when suddenly / a person made of water slides into my body / When the person gets stuck and struggles terribly” (“Sob”)

“I wanna run away from myself” (“Headache”)

“My flesh boils in the immovable body” (“Titicaca”).

These lines generate a feeling of suffocation. Yet if writing is not only a representation of life but an extension of life, a space to become something that life otherwise doesn’t provide, then we can see how the poem allows the speaker to exceed suffocation. Nevertheless, the question of whether these poems are able to overcome the trauma inherent in their expression remains open-ended: the two poems that conclude the book are far from optimistic: “To Be Alive” ends with the line “All is so perilous” and the last poem is entitled “Daily Funeral.”

An important organizing feature is the repetition of the adjective “red” throughout the volume. The repetition is not quite as pronounced as in Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red (1999) where its heavy usage turns the word-as-concept into an active, spectral agent. Here, the usage seems governed either by Hemingway’s injunction to use simple adjectives (especially for color) to avoid fussiness, or by a sort of Symbolism. Red is typically seen as a strong, even violent color, and the insistence upon redness heightens the poems’ edgy tone. Some of the uses are almost redundant: “red roses,” “red wine,” “red blood.” Others are more ethereal and discomfiting: “red wires,” “red thing,” “red glass,” “red evening,” “red sky,” “red infant,” “red stain,” “red pig,” “red string,” “red dew,” or “red water.” In sum, the redness seems illustrative of the protracted maternal nightmare of the collection’s psychic landscape. For instance, in “Lady Yuhwa” we encounter a woman’s “endlessly stretching lips” as she gives “birth to an egg in prison.” The “red sky” is tied to this scene, when the woman’s “silent cry” comes “spilling out like a wound.” This recurring redness is paired with only two other colors—black and white. A note by Jiwon Shin, one of the book’s translators, saying that she bonded with the author over a shared love of Mallarmé, suggests that the starkness of Kim’s colors can be understood as a kind of Symbolism. The limited palette imbues each color with added meaning, supersaturating her poetic images and creating a quasi-mythic, emotional landscape.

Yet, some questions persist.

Reading these poems, I was compelled to examine my own expectations of Korean literature in translation. To what extent does a foreign reader expect a sort of ethnography from their reading material? If I am any barometer, readers of foreign literature are interested in learning about a writer’s culture, society, and/or life. But Kim’s poems are not confessional (which might make them indicative of the writer’s life and culture), nor are they written in a style that’s reflective of a social reality. This makes their specific Koreanness difficult to locate. Was I certain, when reading these poems, that they were Korean? I’m not sure I was. Might Korean literature in translation need to be more Korean than in its original?

These musings tie in with the question of how any national literature folds into world literature canons, and how any writer inhabits a shared imaginative geography with others around the world. On the one hand, Kim’s poems ask us whether any text in translation can embody the aesthetic originality of its source text; on the other hand, we see the traits Kim’s writing shares with writing from other places, which, if read alongside it, allows us to discover new veins of meaning. We might say that, in their dramatic style, Kim’s poems have more of the English writer Stevie Smith in them than they do of the Korean-American poet Myung Mi Kim, despite sharing with the latter a focus on the pain and suffering of Korean peoples, Korean women in particular. The question remains: are “foreign” sources the right reference points by which to understand Kim Hyesoon and her position within Korean literature? Or should we rather look to Korea, where her poems have a social effect and influence other contemporary Korean women writers?

Perhaps the best answer is both: yes, Stevie Smith, yes, Mallarmé, yes, Myung Mi Kim, yes, Kim Yideum, and yes to many more.

Editorial note: An earlier version of this review mistakenly attributed a quotation to translator Don Mee Choi. It now identifies the correct translator, Jiyoon Lee.