Reading Minna Canth’s Children of Misfortune (translated from the Finnish by Minna Jeffery) felt like a jolt of moral clarity. In a year when I stopped apologizing, the play reminded me why anger, when shared and articulated, can still feel invigorating. Canth refuses the lie that oppression is inevitable, insisting instead that the world we inhabit was made and can be remade. There is something bracing, almost ecstatic, about watching oppressed people unite in fury, turning their rage against the lifeless property their masters prize so dearly.

That same refusal of appeasement runs through Hélène Laurain’s On Fire (tr. Catherine Leung from the French), whose blunt, abrasive narrator feels almost instructive in a moment when calls for meek compromise echo as loudly as calls for violence. Laurain offers no heroes, no romanticism, only a clear-eyed account of what resistance actually costs: police brutality, surveillance, isolation, depression. And yet resistance remains necessary, as does art.

If Canth and Laurain speak to the anger of the present, Zekine Türkeri’s A Jihadist Dried Up a Sea (tr. Keko Menéndez Türkeri from the Turkish) does justice to its grief. Few endings have struck me as forcefully as Türkeri’s explanation of the title. Stripped of sentimentality, the piece insists that meaning is not born from grief but constructed against it, and that only by recognizing our shared pain can we find the strength to go on.

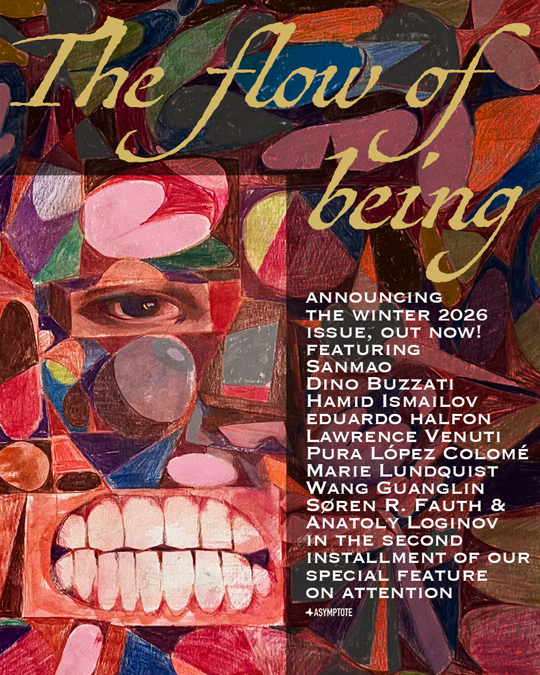

That recognition undergirds Anatoly Loginov’s The Narrow Neck of Being (translated from the Russian by the author himself), a staggering survey of attention in Russian literature. For all its scholarly precision, the essay is bound to the issue’s most politically outspoken works by its insistence that attention and suffering are inseparable. To be aware is to be fragile, mortal, and therefore attuned to the vulnerability of others. Loginov’s call to spend attention lavishly, even on another’s suffering, feels like an ethical compass for an age of ceaseless crises.

I ended my reading in a quieter register with Rokhl Korn’s Four Poems (tr. Pearl Abraham from the Yiddish). Their exactness captures the shared longing of romantic love, but what stayed with me most was Korn’s use of the future tense in “My Wait” and “My Dreams.” Desire, she seems to accept, will never be fulfilled. And still, she grants it beauty.

—Julia Maria, Digital Editor

Reading Zekine Türkeri’s A Jihadist Dried Up a Sea (tr. Keko Menéndez Türkeri from the Turkish) alongside Sidsel Ana Welden Gajardo’s As a Child of a Refugee, I Have Learned That War Lives on Across Generations (translated from the Danish by the author) was devastating. Even knowing, intellectually, that war and displacement scar across generations, both pieces force a confrontation with that truth. Türkeri reminds us that every person in a refugee camp carries a story worthy of more than a report, while Gajardo’s letter to her father wrestles with how trauma persists long after exile, living on in loneliness and the mind. If time heals, these pieces ask, what does healing even look like? Can war ever truly end?

I was struck, too, by A Poetic Psychology of Attention, the interview with Kristin Dykstra, particularly her observation that interruption itself can signify. In a world saturated with stimuli, dissonance becomes not a flaw but a necessity. Estranging ourselves from the familiar may be the only way to recognize what realities truly matter. READ MORE…