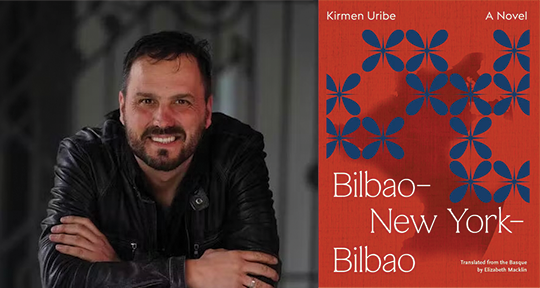

Bilbao—New York—Bilbao by Kirmen Uribe, translated from the Basque by Elizabeth Macklin, Coffee House Press, 2022

“I realized that our dad’s whole family history was made up of round trips, flights, and returnings,” reflects author Kirmen Uribe. Bilbao–New York–Bilbao, a novel which won Uribe the 2009 National Prize for Literature in Spain, stems from the family history in question. Translated from the Basque by Elizabeth Macklin, it is a sort of metanovel that straddles fact and fiction, laying its mechanisms bare. Within the brackets of his own travel—a flight from Bilbao to New York—the narrator’s mind rambles through various elements he would like to weave into his hypothetical novel: interviews, folklore, philosophical reflections, images, and anecdotes. He meditates on structure and process, always on the precipice of making decisions, giving the whole novel the impression that it’s just about to start.

Uribe is from the Basque fishing town of Ondarroa, where the men have historically spent large parts of the year on the water. Urbanization, industrialization, and the mechanization of the fishing industry have by now, however, made the traditional way of life nearly obsolete. As a member of the intermediary generation, the rhythm of this extended round-trip journey is still familiar to Uribe; movement is not a means to an end, but a comfortable and creative mode of being that always ends in a provisional homecoming.

Throughout, the reader senses that his search for the novel’s structure is a search for meaning. Uribe’s desire for the moments that make up his personal, family, and national history to coalesce into narrative is tangible, though he struggles to make them conform. Details, encounters, images—he feels their weight and wants a story to give them coherence. But they resist, and his resulting frustration is echoed by the reader. When a new anecdote begins, we wonder: where does this fit in? Why should I immerse myself in this moment? Is this character major or minor?

Memory has always been the terrain that grounds seemingly disparate moments, and Uribe’s memory is like the ocean maps that his ancestors drew for their fishing journeys; the features depicted are those most salient to the cartographer. Before the time of GPS, Uribe recalls his father drafting a map of his habitual fishing ground off the coast of an uninhabited Scottish island called Rockall. It was a personal map, jealously guarded, that showed the significant underwater features and the migratory patterns of the fish. Rockall echoes through the novel, looming large like a landmark, as it would have been for Uribe in his youth—the place where his father was when he wasn’t home. I looked it up on Google Maps, but as I zoomed out to see where it was in relation to the United Kingdom, it quickly disappeared. READ MORE…