In our new column, Retellings, Asymptote presents essays on the translations of myths, those enduring stories that continue to transform and reincarnate. Here, Hilary Ilkay considers the contemporary rendition of an ancient tragedy by Euripedes, as told by poet Anne Carson and artist Rosanno Bruno in the acclaimed The Trojan Women: A Comic.

Thanks to cinematic blockbusters like Troy and Emily Wilson’s bestselling translation of Homer’s Odyssey, the story of the Trojan War has established itself within the cultural mainstream. However, its continual revival is not just a contemporary phenomenon; as early as 5th century BCE, the mythical war had already taken on legendary status, and was ripe for adaptation and retelling.

Arguably the most tragic of the ancient Greek tragedians, Euripides’s plays are infamous for their bleak explorations of human hubris and divine cruelty. In his lifetime, as Athens was embroiled in the Peloponnesian War, a violent 27-year conflict with rival city-state Sparta, Euripides drew on the Trojan War specifically to reflect on the uncertainty of his time, making a connection between Athenian imperialism and the Greeks’ pretense of invading Troy for the sake of a single woman. Taking its cue from the ending of the Iliad, which features funeral laments from three women characters, Euripides’s play The Trojan Women casts a spotlight on the fates of the wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters of the male heroes—who typically occupied center stage in narratives of war. As a focused treatment of women’s suffering rarely seen in ancient Greek tragedy, the play is a brutal exploration of the commodification of women’s lives and bodies, as well as the ambivalence of “surviving” a tragedy when those remaining have lost all sense of meaning, stability, and security.

Given Euripides’ interest in the experience of women and the retelling of myths, it’s no surprise that his legacy continues through the work of poet and translator Anne Carson, who has received much acclaim for her rewritings of Greek classics. Carson constantly stretches the boundaries of translation in her work, dramatizing how every translation is necessarily its own “version” of the source material and not necessarily a “faithful” replica. In 2006, she published her loose translations of Euripides’s lesser known tragedies under the title Grief Lessons; in 2019, she adapted his infamously bizarre play, Helen, into Norma Jeane Baker of Troy, which interweaves the stories of Helen of Troy and Marilyn Monroe.

Carson’s most recent engagement with Euripides is a collaboration with visual artist Rosanno Bruno, reframing his material in a way that foregrounds the timelessness of women’s trauma, suffering, and victimization. The Trojan Women: A Comic, published in 2021, is a hybrid work of translation that moves from the dramatic stage to the illustrated page, from ancient Greek metrical lines of poetry to colloquial English vernacular. It assigns authorship of the story to Euripides without granting him ownership, dwelling in the space that points to what gets “lost” but also found, when we move from one language and one genre to another.

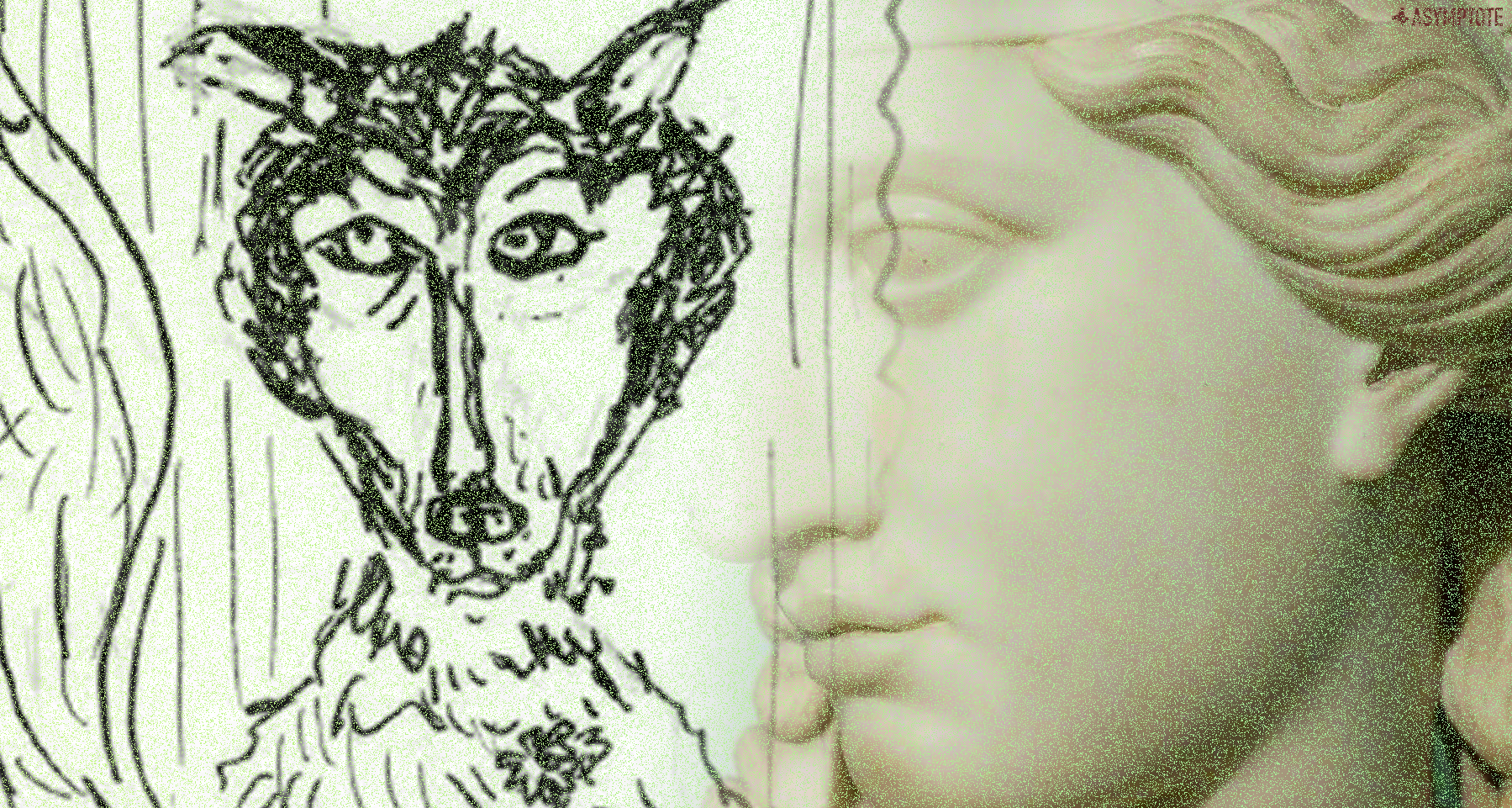

The comic form emphasizes what might otherwise be lost when reading Euripides’s text: that theatre is not just textual, but also visual. The physical book is large, blowing up the scale of the story and foregrounding the importance of seeing alongside reading. Bruno’s black and white illustrations highlight the starkness of the events taking place; the pages, drained of color, appear as if they were photographic negatives. Additionally, Carson and Bruno’s decision to render the gods as natural or artificial objects and most of the mortals as animals emphasizes the harshness of Euripides’s world, in which the former have no common ground with the human actors and the latter are always at risk of becoming debased. This approach also captures the ancient Greek tradition of actors wearing exaggerated masks onstage—a character becoming synonymous with its representation.

Euripides’s play begins with the sea god Poseidon announcing his presence to the audience; the Greek verb can mean something like “here I am,” and in the comic book, the artist devotes the first two-page spread to a giant wave. Mirroring the metatheatrical gesture of Euripides, Carson’s Poseidon says, “My function here is to ‘prologue’ the play,” going on to introduce the set, the time, and the background story, all vividly punctuated with illustrated scenes. The other starring divinity is Athena, who, unlike the Trojan-leaning Poseidon, supported the Greeks. Euripides’s gods are notorious for their sadistic machinations and lack of regard for mortals, and Bruno captures their grandeur by inflating their scale on the page; while Poseidon is drawn as a towering wall of water, Athena is a huge pair of overalls (the brand is “Warhartt,” a play on the fashionable industrial brand “Carhartt”) holding an owl mask—a nod to her status as the goddess of weaving and of wisdom. These gods are “empty” in a sense, pure signifiers who nevertheless have the power to turn the tide of human affairs however they please, which echoes Euripides’s representations of them in his plays: omnipotent, omniscient, and, most frightening of all, easily offended and unforgiving.

Bruno’s illustrations also do much to capture the helplessness and distress of the female characters on the losing side. Andromache, the Trojan hero Hector’s widow, is a poplar tree with a split trunk and dragging roots—her psychological wound rendered visible. Her son Astyanax is a small bundle that rests in her armlike branches, which makes for a visceral, violent scene when the Greeks tear him from her breast, dooming him to death like his father. Another vivid rendering is of one of the play’s central eponymous figures, the dethroned queen Hekabe, who has already lost her husband Priam and their sons to brutal murders, and is on the brink of being separated from her daughters. She becomes “an ancient emaciated sled dog of filth and wrath.” This particular designation of breed implies that while men rule, women are responsible for the labor of dragging the burden; it also translates with great pathos the play’s first glimpse of Hekabe, prostrate on the ground, instructing herself to get up and lift her head.

Similarly, Bruno illustrates the chorus of Trojan women as cows and dogs, appropriate given that the Greek soldiers see them as a pathetic herd, to be either slaughtered or domesticated. When the chorus first appears in the comic, they are holding up signs with numbers and the name Troy: anonymous prisoners of war. At the end, while they await distribution and dispatch to their new Greek homes, they are padlocked behind a fence, screaming for their mothers in speech bubbles.

As the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen occupies a unique position in Euripides’s play— caught between the conquered Trojans and victorious Greeks—and Bruno’s illustrations of her reveal the slippery complexity of her character. She has a “changeable form, sometimes a silver fox, sometimes a large hand mirror.” In the play, Helen uses her wiles to charm her way back into her husband Menelaus’s good graces, so a fox is a natural choice (though it’s worth noting that she walks on her hind legs like a person, and in stilettos, no less). Just as Bruno specifies that Hekabe is a lowly sled dog, Helen is an animal whose pelt prized as a rare luxury item: beautiful on the outside but cunning on the inside, coveted as an object of adornment. As for the other form of the hand mirror, the portrayal drives home her vanity and narcissism as a “femme fatale.” The fact that her form is “changeable” echoes how the play presents her as a woman with no sense of fidelity, hated by both sides. She may have spent the war in Troy, but this is where her association with the surviving Trojan women ends; she is the only one who is safe from enslavement, abuse, or death.

Alongside this movement from written play to illustrated comic is Carson’s translation of the ancient Greek text. Her version basks in anachronism and is not concerned with reproducing the original narration or dialogue, instead opting to translate the pain of these ancient women into a language we can understand. In the play, the broken women express not only grief but also anger and disgust, and Carson intensifies these emotions in her translations of dialogue. Hekabe calls Helen the “why and fucking wherefore of it all,” and Andromache calls Paris “your first-fucking-born”; the chorus laments, “Troy, you made a bad deal: / ten thousand men for a coracle of cunt appeal.” These phrasings may appear crass and shocking, but ancient Greeks certainly insulted each other without the refinement of poetic speech, and as such, Carson makes Euripides speak our language without compromising meaning. In the play, when the chorus of women mourns that they will never see their parents’ homes again, Carson has them ask if they can call their parents. Just as there are limits to what a visual medium can represent, translatability encounters resistance. In moments of extreme anguish, Carson adds the Greek before her translation. When Hekabe learns that the Greeks have murdered her daughter Polyxena, the text reads, “οἲ ’’γα τάλαινα…AH NO. AH NO.” When Andromache learns that the Greeks plan to kill her son, the text bubble reads, “οἶμοι GRIEF,” uniting the original word with its translation on the page and in the reader’s mind.

With such singular techniques, text and illustration come together in charged, affective scenes to show that the Trojan women are more than just passive survivors. When Hekabe learns that she is being given to Odysseus, a strip on the same page features a zoomed in frame of her furrowed brow, with the word “no” appearing multiples times in the eyeballs, and the next page is a solid black background with cascading white “NO”s of various sizes. In Eurpides’s Greek text, Hekabe’s response is the haunting, monosyllabic cry “ἒ ἔ,” which means something like “woe, woe!” By turning the “woe” into “no,” Carson translates Hekabe’s formal exclamation of grief into an emphatic refusal to obey the men dictating her future, a proto-feminist gesture of resistance heightened by the defiant visual representation. When Andromache hears her son’s fate, a chaotic, dizzying drawing of spinning, broken branches dominates the page, dramatizing her disorientation and disintegration. On the penultimate page of the comic, the remnants of Troy are engulfed in fire, with Hekabe and the chorus vanishing in the smoke. The loss of identity for these women who have survived their city’s double destruction threatens to repeat itself in their trauma—but they are not consumed by the flames. The last page is all black except for a tiny circle cutout with a sailing ship and a speech bubble for the chorus. We move from fire to water, from desiring death to persisting in life.

Euripides’s play ends with a sense of necessity: the chorus demands lamentation for Troy but must “go onto” the Greek ships. Carson picks up on this language, but makes it ambiguous: “we go on” could just as well be a statement of resilience, as in “we carry on.” If Euripides ends with despair, Carson grants her Trojan women agency, even if it seems that hostile men and unfeeling gods control their lives.

In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Euripides’s contemporary Thucydides foretold that the events he recorded would “happen again at some time in the same or a similar pattern,” for “such is the human condition.” All telling is retelling. Still, Carson and Bruno’s project demonstrates that the “original” story has no authority over those who want to retell it; myth can be infinitely transformed in its translations, giving voices to those who have been spoken for or marginalized in men’s accounts. Reflecting on the unjust narrative of her life, Carson’s Hekabe pointedly asks, “Can we strangle the Muse?” It is a pithy remark about the responsibility of storytelling as well as a nice callback to Poseidon’s opening speech, in which Carson inserts a reference to Frederick Seidel’s poem “James Baldwin in Paris”: “the leopard pills and eats its trainer every day.” This insight into influence and originality is what makes the comic book so successful. In order for the story to live on, for the Trojan women to continue speaking to us, Carson and Bruno must kill Euripides, even if he is the “keeper” of the myth they seek to retell.

Hilary Ilkay is a scholar and researcher based in Halifax, Nova Scotia. She is a Member of the New Voices in the History of Women in Philosophy Group at the Center for the History of Women Philosophers and Scientists, based at Paderborn University. She has written for Lapham’s Quarterly, Eidolon, and Sententiae Antiquae.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: