In this week’s dispatches, we cover Salvadoran literary news and a special Asymptote event! We begin in London, where members of the Asymptote Book Club came together to chat about our fall book selections—and much more. From there, we delve into updates from El Salvador, including the death of a renowned poet and a women’s literary gathering.

Marina Sofia, Marketing Manager, reporting from the UK

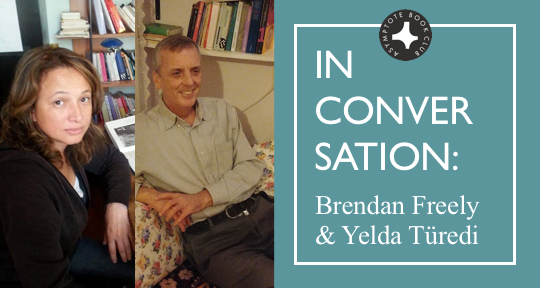

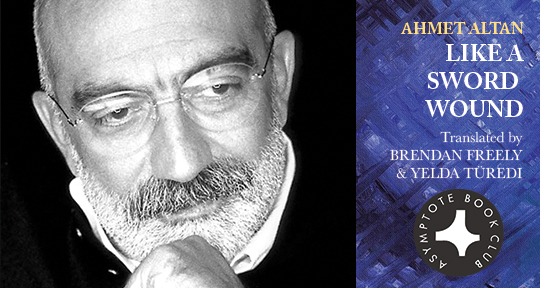

One of the downsides of working for an international literary journal is that our volunteers and readers are scattered all over the world, so in-person gatherings are a rarity. It was therefore all the more special to see members of the Asymptote Book Club in London on November 29 at our first ever meet-up. Designed to be an informal drop-in event to celebrate our first anniversary, it included a quick tour of the current Rights for Women exhibition at the Senate House Library, followed by a discussion over drinks at the recently-opened Waterstones bookshop on Tottenham Court Road. Although we had to compete with a parallel (and noisy) event, our spirits were undampened as we discussed the surprisingly pulpy historical fiction of Ahmet Altan (October’s title) and the acrobatic linguistic challenges of translating Thai writer Prabda Yoon (September’s title). It was a great opportunity to see what readers thought we were getting right (diverse selection of genres, languages and countries; high literary quality) and what they would like to see more of (questions for online discussion; face-to-face events, perhaps including publishers). Thank you to all who ventured out on a windy and rainy evening and contributed to the lively debates!