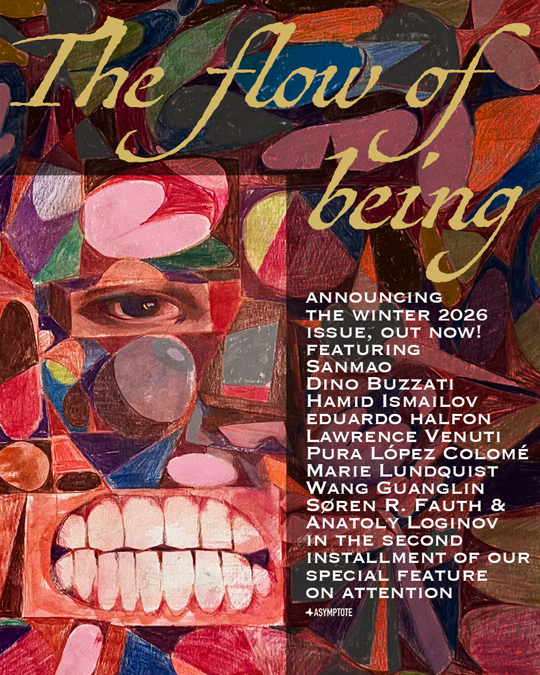

We are not only celebrating the release of our newest issue, the fifty-eighth under our belt, but also fifteen years of working to promote global literature! This is a jam-packed issue, with two special themes and giants in the world of translation interspersed with up-and-coming voices. There is so much to discover, and our blog editors are here to help you navigate the rich offerings on hand!

In a heartwrenching ending to a long poem, Franz Wright wondered:

. . . but

why?

Why

was I filled with such love,

when it was the law

that I be alone?

And therein lies the bind of desire, which is solitude incarnate, which demands that the object of our affections remain distant and suspended, love being most absolute when it resides in wish and conjecture. We are most in love when we hibernate within our singular conception of it, alone. The pain of the unrequited condition consoles, then, by providing us with the most vivid chimeras, pursuing the indefinite with abandon, setting up its own precipitous stakes and utmost heights, the heartening glimpses at pleasure. Such speculations lead easily into self-indulgent ecstasies, but Dino Buzzati is fluent in dreams, and as such he knows that they are only interesting if relayed by someone who sees their truths.

In the earnest and lovely “Unnecessary Invitations”, one perceives the writer who had once said that he believed “fantasy should be as close as possible to journalism”—who understands that a head in the clouds remains connected to the two feet on the ground. The story, addressed to an unnamed lover, sets up several scenarios of the wonderful things the narrator would like to do with his beloved: “to walk . . . with the sky brushed grey and last year’s old leaves still being dragged by the wind around the suburban streets”; “to cross the wide streets of the city under a November sunset”. The scenes are rose-coloured, ripe with affection—but Buzzati follows up each with a cold splash of recognition, in a brilliant switching of registers captured by translator Seán McDonagh:

Neither can you, then, love those Sundays that I mentioned, nor does your soul know how to talk to mine in silence, nor do you recognise, in exactly the right moment, the city’s spell, or the hopes that descend from the North.