This week, find out from our editors-at-large what has been happening around the literary world. Taiwanese literature appears in French translation, introducing a diverse swathe of writers across Taiwan’s linguistic backgrounds to French readers. India continues to reel from the impact of the pandemic, as the literary community remembers the writers they’ve lost, and many organizations stepping up to advocate for pandemic relief work. Read on to learn more.

Darren Huang, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Taiwan

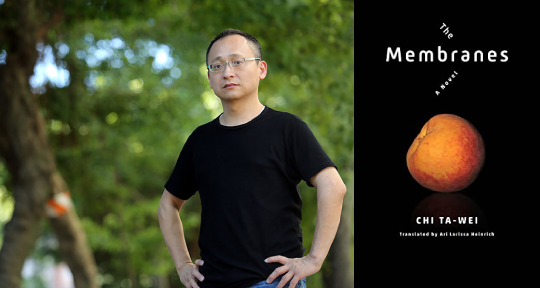

In February, the French publishing company L’Asiatheque released Formosana: Stories of Democracy in Taiwan, a collection of nine short stories by contemporary Taiwanese writers. L’Asisatheque is focused on making available books in translation from Asia, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, South America, and Africa to French readers. In 2015, the company launched a “Taiwan Fiction” series, led by editor Gwennaël Gaffric, who is also a Chinese translator and professor in China Studies at the University of Lyon. The series seeks to amplify Taiwanese literature with themes of environmentalism, cultural identity, Taiwanese dialects, gender, postcolonialism, and the impacts of globalization. The series has published a number of modern classics of Taiwanese literature in French including A City of Sadness by Chu Tien-wen and Wu Nien-jen, The Membranes by past contributor Chi Ta-wei (recently reviewed in our blog), and multiple works by Wu Ming-yi, including The Man With the Compound Eyes and his novella, The Magician on the Catwalk.

In Formosana, the writers grapple with turbulent periods in Taiwanese history, including that of Japanese colonialism, the White Terror, martial law, and democratization. The stories also contend with social issues, such as nativist movements, LGBT rights, and environmentalism. In a recent interview, Gaffric discussed his choice of centering the collection on the theme of Taiwanese democracy. He believes that though there is increasing coverage of Taiwan in the French press, most French people do not understand its historical and cultural intricacies. He states: “We attempt to allow people to understand the fate of Taiwan from the past to the future, through various types of literary works which provide different channels and voices.” For his next book, Gaffric plans to publish the works of indigenous writer, Syaman Rapongan, to introduce indigenous writing to French readers.

On May 29, Taiwanese literature was also highlighted in France when Chi Ta-wei was invited to join the ninth annual “Nuit de la literature,” organized by the Forum of Foreign Cultural Institutes in Paris (FICEP). A reading of Chi’s “Pearls,” one of the stories from his eponymous science-fiction collection, was conducted in both English and Chinese at the virtual event with the author and Gaffric. READ MORE…