This is the first in a two-part series that explores the indeterminate translation effects of foreignization and domestication, as illustrated by Hoàng Hải Thủy’s 1973 Vietnamese adaptation of Madame Bovary. Read the second part here.

Note: The below version has been revised to reflect important corrections. Lawrence Venuti’s theoretical framework, as reflected in the revised essay, does acknowledge the subaltern’s perspective and show that domestication and foreignization encompass both discursive approaches and their multifaceted effects.

Since the earlier version did not fairly reflect the full implications of Mr. Venuti’s work, the author owes Mr. Venuti an apology and would like to thank him for his forbearance and collegial support.

In 1813, Friedrich Schleiermacher, the German translator of Plato, had proposed that a translator has two choices, “either such translator leaves the author in peace as much as possible, and moves the reader towards him; or the translator leaves the reader in peace as much as possible, and moves the author towards him.” The former technique could be defined as foreignization, and the latter domestication. Today translation scholar Lawrence Venuti has expanded on Schleiermacher’s perspective by constructing an ethics of difference in translation. According to Venuti, translations geared toward domestication effects risk perpetuating certain uncontested beliefs in the maintenance of the status quo. As a corrective, he has proposed a meticulous yet adaptable theoretical framework that can illuminate any translation, regardless of language and culture, regardless of their status as dominant or dominated, major or minor. In his view, foreignizing translations can expand the linguistic and stylistic resources of the translating language by broadening the parameters of readability.

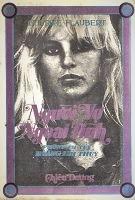

If we define foreignizing as a translation approach that creates noticeable effects and variations from the prevalent standard, and domesticating as conforming to pre-existing norms, how do we gauge these effects against a translator’s stated intention, his unconscious bias, inadvertent omissions or errors? My essay attempts to illustrate these questions by discussing Hoàng Hải Thủy’s Người Vợ Ngoại Tình—his 1973 adaptation of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary.

Hoàng Hải Thủy, whose real name was Dương Trọng Hải, was born in 1933 in Hà Đông, North Vietnam. He immigrated south in 1951, four years before the Southern territory officially became the Republic of South Vietnam (RVN)—an independent nation partitioned from Communist North Vietnam at the Seventeenth Parallel. Hoàng Hải Thủy’s career more or less spanned the RVN’s twenty-year existence (1955-1975), during which he worked as a journalist, translator, essayist, and fiction writer, gaining a cult following for his deft adaptations of both popular and literary fiction from the West. His iconic works, among others, include Chiếc Hôn Tử Biệt (Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying), 1956; Kiều Giang (Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre), 1963; Nổ Như Tạc Đạn (Cleve Adams’ Sabotage), 1964; Tìm Em Nơi Thiên Đường (Daphne du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel), 1965; Đỉnh Gió Hú (Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights), 1969; Bẫy Yêu (Ian Fleming’s From Russia With Love), 1970; Người Vợ Ngoại Tình (Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary), 1973; and Tiếng Cười Trong Đêm Tối (Vladimir Nabokov’s Laughter in the Dark), 1975.

Jailed at various times during the post-reunification period for sending anti-communist poems and essays to overseas Vietnamese magazines, Hoàng Hải Thủy was allowed to leave Vietnam for the U.S. in 1994. He settled in Virginia, where he resumed writing and adapting crime fiction—mostly John Grisham novels—for Vietnamese readers. Hoàng Hải Thủy died of COVID-19 complications on December 20, 2020, leaving behind a prolific legacy of some eighty works. [1]

In the late 1950s to early 1960s, before Hoàng Hải Thủy came into his own, South Vietnam’s translation market was still developing. Vietnamese literary translators—who were few and far between—mostly read French, English, and Mandarin. Emphasizing accessibility as the main objective, the critic and translator Mặc Đỗ proposed that a distinction shouldn’t be made between translating from the original and from a translation of the original. [2] He similarly believed that the line between a translation and an adaptation should be flexible, since the goal was to help the average Vietnamese reader overcome the fear of foreign cultures. Mặc Đỗ noted however that certain words in a Western novel remain untranslatable (the word caddy for example), in which case the original expression should be kept intact with a translator’s footnote. Finally, in discussing ways to translate personal and place names, Mặc Đỗ emphatically discouraged the prevalent practice of deferring to Mandarin or French pronunciations as reflecting a “slavish mindset that readily accepts [the colonized condition].” He proposed keeping personal names in the original language or “Vietnamizing” them in such a way as to reflect their essence. Thus Mặc Đỗ, while advocating for greater access of translated work for South Vietnamese audience—namely, bringing foreign authors closer to the reader—could be seen as proposing a foreignizing view in translation by rejecting the then practice of transliterating proper nouns based on either French or Mandarin.

In the late 1960s through 1975, the demand for translated works increased exponentially due to the explosion of popular culture as a result of American influence, the rise of women readership for serialized fiction—or feuilleton—published in daily newspapers, and the expansion of higher learning institutions that produced students whose linguistic ability proved inadequate to their yearning for diverse cultural contexts. At the height of the Vietnam War, translated works—which included adaptations—accounted for 80 percent of all books published. [3]

While proliferation of translated works reflected South Vietnam’s desire to look outward, adaptation, a hybrid approach, represented a turning inward as self-protection. The escalating war had severely impacted the economy, destabilized the countryside and decimated agricultural resources. Conspicuous American presence and permissive cultural mores prompted certain sectors to advocate for a return to one’s traditional roots. Thus the most prevalent feeling among the populace was a sense of estrangement from one’s time and place, combined with a desire to be transported to an idealized, prewar sanctuary.

In a sense, Hoàng Hải Thủy’s adaptation of Madame Bovary happened during a time when South Vietnam had collectively become Emma Bovary in its need to simultaneously look forward and backward. [4] In the freewheeling atmosphere of wartime Saigon, his adaptation offered a more flexible option than translation because it left open the issue of copyright permission, at the same time providing him with a ready-made framework to which he could freely add his own flourishes.

To Hoàng Hải Thủy, the work’s preexisting structure also functioned as aesthetic, critical, and commercial guarantee—presumably it had been editorially vetted in its first iteration, garnering critical acclaim and commercial success in its original environment. [5] For this debt Hoàng Hải Thủy always made sure that all his adaptations bear references to the original works and authors. Nevertheless, he provided the following justifications for his “Vietnamization” of Western novels—a strategic manifesto advocating for cultural assimilation, i.e., domesticating effects that make foreign aspects of a particular work less noticeable:

I found that readers who lived during the time when I wrote feuilleton novels … had never used a telephone, gotten on an elevator, flown on an airplane, or stayed in an air-conditioned room. These readers would have a hard time understanding a [Western] story that mentioned telephones and elevators. If they couldn’t understand they wouldn’t go on reading. The goal was to entertain my kinsfolk. Entertainment was, and is, a basic human need. A component of art. I wanted to give my readers moments when they could forget the unpleasant life around them. While reading, they might find it hard to follow a female character named Liz, at times called Lizzie, and a few pages later referred to as Elizabeth. I had to figure out which European or American novels have plots that conceivably could happen to Vietnamese people, could take place in Vietnam. So I shifted Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre to Dalat, My Cousin Rachel to Hue, and Scorpion Reef to Danang… [6]

At first glance, Người Vợ Ngoại Tình seems anomalous. Unlike his other adaptations during this period—which were modern romance or spy novels set in well-known South Vietnamese cities—in this instance Hoàng Hải Thủy employed the trope of fairy tale to turn Flaubert’s world into a shifting milieu that represents both the French author’s Normandy and an impressionistic version of North Vietnam that at once evokes and resists a direct identification with reality. At any rate, it seems adapting Madame Bovary was another of Hoàng Hải Thủy’s tributes toward his female fan base. In a 2011 interview, he admitted many of his adaptations had been done with female readers in mind, as he considered himself an Âm Nam—a “feminine male, spineless as spoiled noodle and mushy as rotten rice.” [7] (His strangely misogynistic comment reminds me of Flaubert’s assertion, “Emma Bovary, c’est moi!”) One could imagine harried, cash-strapped South Vietnamese women readers identifying with Emma Bovary’s sensuality and romanticism. Her taste for luxury and reckless comportment would provide these readers with a brief respite from the hectic demands of their wartime existence.

[1] See https://hoanghaithuy.wordpress.com/ and https://www.tvvn.org/hoang-hai-thuy-nguyen-ngoc-chinh/

[2] Mặc Đỗ, “Công Việc Dịch Văn” (“The Task of Literary Translation”), Sáng Tạo Magazine, vol. 1 (October 1956). See also Võ Phiến, Văn Học Miền Nam Tổng Quan (Văn Nghệ, CA: 2000), pp. 303-304.

[3] In sum, translations in all subjects totaled 1543 works during the RVN’s twenty-year period, with translations from French topping the list at 499, followed by popular fiction from Taiwan and Hong Kong at 358, and the US at third place, with 273 translated texts. See Nguyễn Văn Lục, “Một Số Nhận Xét về Sách Dịch Tại Miền Nam trước 1975 của Một Người Đọc” (“A Reader’s Perspective on Translated Works in Pre-1975 South Vietnam”), talawas 9/30/2004.

[4] Hoàng Hải Thủy, Người Vợ Ngoại Tình (Chiêu Dương, Saigon: 1973) was first serialized in a daily newspaper and later published in book form.

[5] See https://hoanghaithuy.wordpress.com/2013/05/17/no-nhu-tac-dan/, in which Hoàng Hải Thủy discusses his adaptation process generally and also as it pertains to Cleve Adams’ Sabotage, in response to Nhị Linh, a translator and critic living in Vietnam.

[6] Ibid. Original passage in Vietnamese: “Tôi thấy đại đa số người Việt thời tôi viết truyện phơi-ơ-tông–những năm 1960–chưa một lần dùng tô-lô-phôn, chưa một lần lên xuống thang máy, đi máy bay, ngụ phòng máy lạnh. Những người này đọc truyện thấy khó hiểu khi trong truyện có việc dùng điện thoại, lên xuống thang máy. Khi truyện khó hiểu họ không đọc. Tôi chủ trương viết truyện giải trí cho đồng bào tôi. Giải trí là một nhu cầu của con người. Giải trí là một chức năng của văn nghệ. Tôi muốn mang lại cho người đọc truyện tôi những giây phút họ tạm quên cuộc sống khó chịu quanh họ. Tôi thấy người đọc khó nhớ, khó hiểu, khó chịu khi đọc truyện nào nữ nhân vật lúc tên là Liz, lúc tên là Lizzie, vài trang truyên sau là Elizabeth. Tôi phải tìm những tiểu thuyết Âu Mỹ nào có cốt truyện có thể xẩy ra được với những người Việt Nam, xẩy ra trên đất Việt Nam. Tôi cho Ðỉnh Gió Hú, Kiều Giang xẩy ra ở Ðàlạt, Tìm Em nơi Thiên Ðường xẩy ra ở Huế ….” [all English translations quoted above, unless otherwise noted, are by Thuy Dinh]

[7] Hoàng Hải Thủy’s original statement, “Tôi bản tính yếu sìu—Tử vi là Âm Nam: Đàn ông mà tính nết như đàn bà ….Tôi mềm như bún thiu, như cơm vữa.” (From the 2011 interview with Lê thị Huệ at Gió O)

Thuy Dinh is coeditor of Da Màu and editor-at-large at Asymptote Journal. Her works have appeared in Asymptote, NPR Books, NBCThink, Prairie Schooner, Rain Taxi Review of Books, and Manoa, among others. She tweets @ThuyTBDinh

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: