This is the second in a two-part series that explores the mixed translation effects of foreignization and domestication, as illustrated by Hoàng Hải Thủy’s 1973 Vietnamese adaptation of Madame Bovary. Read the first part here.

Note: The below version has been revised to reflect important corrections. Lawrence Venuti’s theoretical framework, as reflected in the revised essay, does acknowledge the subaltern’s perspective and show that domestication and foreignization encompass both discursive approaches and their multifaceted effects.

Since the earlier version did not fairly reflect the full implications of Mr. Venuti’s work, the author owes Mr. Venuti an apology and would like to thank him for his forbearance and collegial support.

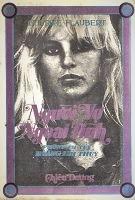

Hoàng Hải Thủy’s adaptation showcases his wit, creativity, and lyricism. In Người Vợ Ngoại Tình, Charles Bovary becomes Trần văn Bô, an inspired choice since the name represents both a phonetic and metaphorical rendering (although by Vietnamese convention Trần would be his family name and Bô his given name). Bô is a round, onomatopoeic sound that in Vietnamese evokes a chamber pot, and an idiot’s babbles.

Hoàng Hải Thủy changes Emma’s name to Ánh—which means “shadow,” “reflection,” and “refracted light” in Vietnamese. This domesticating approach nevertheless reflects Hoàng Hải Thủy’s concise and elegant understanding of Emma Bovary. In Flaubert’s original context, mirrors and windows are employed to accentuate Emma’s outsider status—she’s a reflected image, being gazed at by her solipsism, by other men. She is elusive, insubstantial, but also transcendent.

Hoàng Hải Thủy’s intuitive approach is also apparent in the way he transforms other character names into a kind of Vietnamese shorthand that’s intuitively Flaubertian: Léon becomes Thầy Ký Lợi—as he is being addressed, Vietnamese style, by both his profession (law clerk) and his first name Lợi. “Ký”—while literally means clerk, also implies a modest social position and a philistine mindset that are not likely to change with time—thus mirroring Flaubert’s treatment of Léon Dupuis in the original. The aristocratic cad Rodolphe becomes Bửu Quý. “Bửu” in the Vietnamese context immediately signifies royal lineage since this family name could only be used by descendants of the Nguyễn dynasty.

As indicated, Hoàng Hải Thủy’s adaptation is imbued with a North Vietnamese sensibility. This clearly was not an issue for South Vietnamese readers as many well-known writers and translators in pre-1975 Saigon, like Hoàng Hải Thủy, happened to be Northern transplants who had immigrated South during the 1954 Partition. North Vietnamese usage also happened to be the standard in broadcasting and publishing.

Hoàng Hải Thủy’s use of shifting pronouns cleverly captures both the colloquial, “peasant” nature of Northern Vietnamese syntax and Flaubert’s innovative style. For example, “bác” (“elder uncle”)—as second-person (familiar) pronoun or impersonal, “ironic” third-person pronoun—is a warm, sardonic term used for old friends or drinking buddies. In this case, Hoàng Hải Thủy’s ingenious adoption of bác as an indirect third-person point-of-view that imperceptibly shifts to second-person direct pronoun can approximate Flaubert’s use of the pronoun on which shifts ambiguously between first person and third person in the original:

Bác nào ngồi lâu mỏi lưng thì bỏ ra sân đi tản bộ vài vòng … [1]

(Quand on était trop fatigué d’être assis, on allait se promener dans les cours …) [2]

(When one (I)/they (we) was/were tired of sitting down, one (I)/they (we) would go for a walk in the yard …)

Thus, like Flaubert, Hoàng Hải Thủy’s use of eliding pronouns when depicting Ánh and Bô’s lively wedding banquet provides the reader with an impression that evokes both the panoramic and personal experience of this event. [3]

Bửu Quý/Rodolphe’s register of the pronoun “em” (she) when thinking about Ánh is also uniquely Northern: it fully captures his cynical and predatory attitude toward her—a naïve provincial begging to be seduced. And while Flaubert’s phrase, “Pauvre petite femme! Ça bâille après lamour, comme une carpe après leau sur une table de cuisine” (“Poor little woman! She’s gasping for love like a carp gasping for water on a kitchen table”) [4] is most likely misread by Hoàng Hải Thủy as “Sau mỗi lần ái tình, em nằm ngáp chán như cá chép trên thớt.” (“After lovemaking [with her husband], she lies yawning, bored as a carp on the cutting board”), his free rendering, as a domesticating technique with its employment of the Vietnamese idiomatic phrase “carp on the cutting board” works well here since it captures the spirit of Flaubert’s original by showing Rodolphe’s intuitive grasp of Emma’s romantic confusion—she’s “bored after lovemaking” because she doesn’t love Charles—while Rodolphe, as a seasoned seducer, knows that good sex can be had without love.

So did Hoàng Hải Thủy—in employing a North Vietnamese syntax which was then the standard in South Vietnam writing—create domesticating or foreignizing effects, or both, with his adaptation? While Hoàng Hải Thủy thought he had intended a domesticating approach for his adaptation, his approach seems inconsistent, haphazardly applied, not always consciously reasoned. A farmer with a Vietnamese name, Tư Bột (Monsieur Bizet in Flaubert’s version) is from Canh-Căm-Poa (transliteration of Quincampoix). Hoàng Hải Thủy’s casuarina and phoenix trees stand out from Flaubert’s beeches and Marguerite daisies. On her daily walk with her pet dog, Lili (Djali in Flaubert’s original), Ánh would pass an abandoned Buddhist pagoda and a lotus pond on a desolate stretch near a Normandy beach. Arguably, these inconsistencies can be seen as both domesticating and foreignizing in its quaint parallel to Flaubert’s thematic construction. In Madame Bovary, Emma is depicted as alienated from her environment in her yearning for exotic locales and showy penchant for Chinese porcelain, Turkish incense, and Algerian knickknacks.

It is possible Hoàng Hải Thủy’s recreation of Flaubert’s novel as a hybrid universe—with North Vietnam superimposing on nineteenth-century Normandy—was an attention lapse, rather than a conscious effort. In 1973, besides Người Vợ Ngoại Tình, Hoàng Hải Thủy also adapted Charles Williams’ Scorpion Reef and the 1953 film Roman Holiday (screenplay by Dalton Trumbo) for South Vietnamese daily papers. In addition, he also translated, at a publisher’s behest, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude from Gregory Rabassa’s English translation. [5] While earning a comfortable salary, Hoàng Hải Thủy admitted he was stretched thin by the sheer demand of serialized works, which left little time for endeavors that could make him a “better” writer. It is thus likely that his juggling of multiple storylines under various deadlines would lead to textual irregularities. [6]

Since in his lifetime Hoàng Hải Thủy did not discuss his working process on Người Vợ Ngoại Tình, we will never know why his adaptation eliminates nearly half of Flaubert’s novel. In his version, there is no visit by the Bovarys to La Vaubyessard, while in Flaubert’s novel such visit represents a seminal event that “had opened a breach in [Emma]’s life, like one of those great crevasses that a storm can tear across the face of a mountain in the course of a single night.” [7] In addition, the relationship between Ánh and Thầy Ký Lợi (Léon) remains platonic after the latter left for Paris; there is no mention of the opera performance where Emma and Charles reencounter Léon, no infamous seduction scene in a sealed carriage, no weekly trysts in Rouen, no layers of subterfuge that culminate in Emma’s financial ruin.

In Hoàng Hải Thủy’s version, Ánh ingests arsenic shortly after being abandoned by Bửu Quý. Her death is not drawn out but dispatched summarily, after which “life returns to its peaceful rhythms for Dr. Trần Văn Bô.” Người Vợ Ngoại Tình ends not with Bô’s bankruptcy, his death from grief, nor his daughter’s Dickensian apprenticeship at a cotton mill, but with the housemaid Nhài’s appropriation of Ánh’s entire wardrobe and her subsequent elopement—theo tiếng gọi của ái tình (driven by love’s calling)—with a no-name waiter from Rouen. While Nhài’s desertion from the Trần household mostly follows Flaubert’s plot, the sly, caustic tone adopted by Hoàng Hải Thủy at the end of Người Vợ Ngoại Tình—as opposed to Flaubert’s detached style—suggests history may repeat itself as an indictment of Western romance—this seems foreignizing. Nhài, like Ánh, possesses no free will, disrupts no social order, but simply reenacts a predetermined fate assigned to all transgressive women—regardless of their socio-economic status. While it’s not clear if Hoàng Hải Thủy’s coda reflected a pre-emptive gesture to forestall the RVN’s censorship of immoral literature, it might have provided sufficient caution to temper any escapist fantasy that Người Vợ Ngoại Tình could offer a 1970s South Vietnamese female reader. This could be defined as a foreignizing effect as it goes against the happy-ending trope of a typical romance novel.

Additionally, domestication in Hoàng Hải Thủy’s case may simply be a suspension of disbelief more analogous to foreignization. While the text’s fluency provided South Vietnamese readers with the similitude of experiencing Flaubert’s original, the readers knew they were reading an adapted work—given Hoàng Hải Thủy’s explicit acknowledgment of Flaubert, his publisher’s introduction summarizing Flaubert’s 1857 obscenity trial and the 1949 film adaptation of Madame Bovary by Vincente Minnelli. Any adaptation trends during Hoàng Hải Thủy’s time, if omitting the mention of authors or original sources to sustain the illusion that the adaptation was the translator’s original work–would be considered more “domesticating” than Hoàng Hải Thủy’s approach.

Domestication and foreignization are thus fraught with mutable complexities when gauged against the context of a marginalized, post-colonial country. It appears that South Vietnamese readers of the 1970s, long attuned to war, migration, and colonization, could juggle multiple contexts when reading Người Vợ Ngoại Tình—that it is a French novel adapted by a North Vietnamese writer working in South Vietnam, where North Vietnamese syntax was actually considered the standard. These layered, shifting tensions in Hoàng Hải Thủy’s adaptation correspond poetically with Flaubert’s onion construction in the original: the French author’s indirect narrative style, Charles Bovary’s absurdly baroque hat, and Emma’s Orientalist affectations vis-à-vis her French provincial landscape.

Hoàng Hải Thủy’s adaptation would serve as a useful model for the study of intersectionality between post-colonial, gender, and translation theories. But due to the unstable political period toward the end of the Vietnam War, and the loss or ideological erasure of many South Vietnamese literary resources during the post-1975 period, we simply don’t have sufficient information to fully assess the impact of this adaptation on his 1970s audience.

To this day, there exist only two known (and substantially familiar) Vietnamese translations of Madame Bovary that came after Hoàng Hải Thủy’s adaptation—they were published during Vietnam’s postwar period—in 1976 and 1978, by Trọng Đức and Bạch Năng Thi, respectively. These works remain controversial due to their mechanical approach to foreignization: their phonetic transliteration of personal and place names deemed too confusing or maddening to Vietnamese readers, awkward use of pronouns, turgid prose, and multiple errors related to vocabulary and syntax. In a sense, their Marxist interpretation and their “faithful” rendering of Flaubert’s novel, by adhering to post-Vietnam War’s ideological interests, could be seen as leaning toward domestication.

[1] Hoàng Hải Thủy, Người Vợ Ngoại Tình, p. 47.

[2] French text of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary (Gallimard: 2001), p. 78 (with introduction and notes by Thierry Laget).

[3] The English rendering of Flaubert’s pronoun on as they in several translations (i.e., J. Lewis May (1950), Francis Steegmuller (1957), and Lydia Davis (2010)) does not seem as effective—for it removes the ambiguity between the personal and collective points-of-view in Flaubert’s original text.

[4] Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary, tr. by Francis Steegmuller (Random House: 1991), p. 147.

[5] Hoàng Hải Thủy completed the translation and was paid for his effort but the book could not be published. Marquez’s close friendship with Fidel Castro and his criticism of American involvement in the Vietnam War was considered too politically sensitive from the South Vietnamese government’s perspective.

[6] For example, Vietnamese translator Nhị Linh has noted Hoàng Hải Thủy’s narrative incongruities in the latter’s adaptation of Cleve Adams’ Sabotage—an achievement deemed mesmerizing but nonetheless marred by unexplained detours, unresolved arcs, and inconsistent characters.

[7] Steegmuller, p. 63.

Thuy Dinh is coeditor of Da Màu and editor-at-large at Asymptote Journal. Her works have appeared in Asymptote, NPR Books, NBCThink, Prairie Schooner, Rain Taxi Review of Books, and Manoa, among others. She tweets @ThuyTBDinh

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: