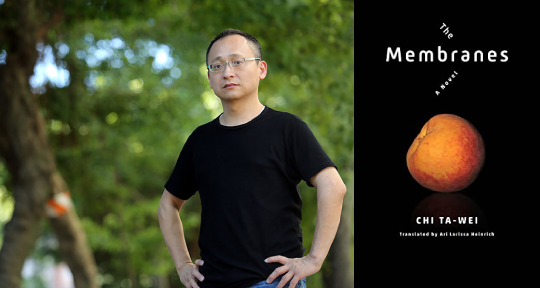

The Membranes by Chi Ta-wei, translated from the Chinese by Ari Larissa Heinrich, Columbia University Press, 2021

Dwelling on a female classmate’s romantic advances in her youth, and belatedly cognisant of her learned aversion towards all forms of intimacy, the thirty-year-old Momo realises the incongruence of the one self-guided decision she had made in her life—to become a dermal care technician: “She could just as easily have chosen a more solitary profession, like a novelist. Why did she have to choose a job reliant on intimacy?” It is the year 2100 and humanity, terrified of the ultraviolet rays seeping through the depleted ozone layer, has evacuated from land en masse to settle on the seabed. Amidst the residual trauma of the sun’s lethal rays, the dermal care trade booms and Momo climbs the profession steadily, eventually becoming the owner of Salon Canary and something of a celebrity in T City. As Momo spends her days massaging her wealthy clients with M skin—a technology that gives her access to their private lives—what she cannot shake off is the feeling that “there was at least one layer of membrane between her and the world.”

In The Membranes, Chi Ta-wei, renowned Taiwanese novelist (and past Asymptote contributor), tackles a central problem of existentialism: how do we account for the estrangement between ourselves and the world? The thrilling sci-fi classic (originally published in 1995) then proceeds to compellingly insist on exploring the question’s social dimensions, getting under the skin of its queer, inscrutable protagonist. A slim, intelligent novella that ambitiously projects a militarised and corporate new world order in the rubble of environmental collapse, Chi’s brand of world-building is equally invested in envisioning new global formations as it is in attesting to emerging sexual subjectivities. It bristles with the emancipatory energy that characterises the novels coming out of post-martial-law Taiwan. Read together with works such as Chu T’ien-wen’s Notes of a Desolate Man or Qiu Miaojin’s Notes of a Crocodile and Last Words from Montmartre, English readers can now appreciate a fuller scope of the queer efflorescence unleashed in the experimental fiction of Taiwan’s nineties and the internal heterogeneity of its cultural moment. Ari Larissa Heinrich’s translation of Chi’s award-winning work comes a quarter of a century after its Chinese publication, but contemporary readers will relish going back to the future in a work that ventriloquises our present, its conjectures at once anachronistic and prophetic.

One prescient aspect of the novella is in how it anticipates the ways we have been forced to develop new intimacies with our technologies, inadvertently replacing the sensuous world of touch with a plethora of invented surfaces, transforming our relationship to the physical world. In this reality saturated with ways of mediating touch (but never actually touching), Chi’s characters are formed by their pact with these machines and their makers, and this ambivalent alliance precipitates new forms of attachments and dysphoria. At age seven, Momo is diagnosed with a mysterious virus and has to spend her childhood years quarantined in a sterile hospital ward, her only means of contact with the world limited to “video conference calls” until, one day, a young android girl named Andy is introduced. Deprived of her mother’s presence, she despises the call as a way to “replace hugging,” and finds her erotic desires aroused by her disinfected android friend. What Momo did not know, however, was that Andy was not another body but her body, designed specifically to be merged into one (indeed, also to transform Momo’s biological sex). When Andy vanishes after the surgery, Momo begins to feel a gaping loss she never quite recovers from. In Chi’s universe, the act of conventional parenting is replaced by the omnipresence of these technologies and cyborgs who, in loco parentis, irrevocably refashion one’s sense of self. Thoroughly disgorged from the template of the nuclear family, it brilliantly opens up the liberating (if also painful) possibility of inventing new forms of kinship and sexual identities, enabled by the intersection of human and machine.

At this point, readers acquainted with posthumanism might recall Donna Haraway’s influential essay from 1985, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” where she provocatively suggests: “Why should our bodies end at the skin, or include at best other beings encapsulated by skin?” It’s easy to see The Membranes happily hanging out in Haraway’s cyborg utopia (Heinrich suggests in his afterword that the essay is one of the author’s theoretical touchpoints), but something sinister, in fact, undergirds this fantasy of hybridity in Chi’s book. In the no less cyborgian but far more dystopian reality of The Membranes, Man meets Machine in a way that isn’t invested with the eroticism of creating something new, but mediated by capitalism to automate the human for profit. Momo’s M skin, which optimises her clients’ pleasure insofar as she gains unfettered access to their haptic lives (“anything from scratches or mosquito bites to work, sex, meals”)—is what surveillance capitalists and their androids dream of:

Put simply, imagine the body is an old-style tape recorder and M skin is a cassette: every stimulus experienced by [her client] Tomie Ito’s body was recorded like a sound. When Momo got the cassette and made a copy, she could play it in the tape recorder of her own body. And when playing it back, she experienced the pulse of sounds beating in her own body like the violent cacophony of a symphony without notes.

What stands out in Chi’s approach to science fiction is that he does not only emphasise the way science shapes the individual, but also how fiction as a technology can reimagine the extensions and contours of the self. Without giving away the major plot twist that occurs near the end of the novella—so well-built that the feat of the entire narrative hinges on its belated realisation—one way to characterise The Membranes would be to understand it essentially as a book about reading. Indeed, beneath the alluring veneer of the novella’s cutting-edge inventions, one archaic technology persists into the future: writing. The kind of literacy needed to decode this technology, however, is not the data literacy that Momo has acquired—which purports to demystify the process of knowing the Other—but, to borrow again from Heinrich’s illuminating afterword, a kind of “promiscuous literacy.” The youth of Taipei’s nineties were voraciously imbibing all kinds of cultural materials that streamed in from the world—distributing them in cinemas, bars, universities, night markets—and their literary output began to wear their promiscuous provenance on their sleeves. In this regard, T City, circa 2100, hyperbolically enacts the ethos of Taipei’s promiscuous nineties.

For all its futurism, Momo’s cultural touchpoints are decidedly retro, a heady mélange of twentieth-century works and events: canaries remind her of their sacrifice as sarin detectors during the Aum Shinrikyo gas attacks in Tokyo as much as the caged birds in Manuel Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman; the act of stripping reminds her of Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler; the spectre of AIDS, although largely eliminated with a vaccine, looms in her mind. Of filmmakers, Momo references Almodóvar, Bergman, Riefenstahl, Truffaut, Visconti. As she tries to understand her identity through history, readers also find their curiosities piqued: what is this twenty-second body doing with a twentieth-century mind? How do our cultural texts come to shape our sense of self? Indeed, these cultural memories are available to her because the publishing conglomerate MegaHard (where Momo’s mother is the director of public relations) seeks to preserve the past—in all its irreducible infinity—on laserdiscs, an archive giddily Borgesian. Nothing new, however, seems to be made in this culture. Under the influence of these portable worlds, Momo grows up to become a consummate comparativist, measuring her life according to these anachronistic cultural moments and, on the way, accruing a unified sense of self even while it is dispersed amongst these worldly texts.

At its core, the book offers this moving account of queer personhood: a model of the self not as internally and eternally consistent, but a patchwork self composed by a world of narratives and cultural fictions, past and present. Detractors might question what is “Taiwanese” about a novel whose intertexts are European arthouse cinema, Japanese pop culture, and a mish-mash of world literature, with scarcely a reference to Taiwan. But this is the question the novella confidently poses back to its skeptics: who is Momo if not a composite of these cultural texts? Who are we but a sum of the fictions we find on our shelves? In The Membranes’s cultural short circuit of the self, it dawns on the reclusive Momo that she is Momotarō is Draupadi is Sun Wukong; her origins are transnational and intertextual. She does not know it yet, but while she is being moulded by these fictions, she shape-shifts, as if to indicate to the reader that one should not obsess over identity, but potentiality. Then, a flagrant, laissez-faire style of reading, with no allegiance to artificial boundaries, might be what saves us from the solipsism of the self.

There is a humorous anecdote in the book’s afterword, where Chi relates how, in the 1990s, his peers in university read Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble as “science fiction written in jargon.” It is unsurprising to find this submerged reference, given that Butler’s advocacy for a citational understanding of the self is foundational to queer theory, but what is fascinating about this story is how, when translated into a different cultural context, not just gender but genre begins to bend. Readers slowly come to understand that Momo is a novelist—one caught in the act of inventing her own gender and genre. Writing the self into being from a hodgepodge of cultural texts—that is what’s elemental to queer life, especially for those scripted outside Euro-American sexual histories. She is a novelist insofar as our understanding of authorship is made flexible to contain the practices of citation, intertextuality, and derivation—rather than judged against standards of originality, authenticity, and faithfulness. In any case, those of us who make a life out of texts know intimately how false this binary is: we are what we read. Books—this most archaic membrane—rather than act as prohibitive layers, perform their absorptive, connective work.

Membranes—from the Latin membrum: limb, member of the body, prosthetic—and how they form us, is the keen insight of this unabashedly literary-minded work of immense imagination, a precise study of an unforgettable character and her cyborgian consciousness. Beneath its troubling view of a world plunged into crisis, there is still a hint of humanism in the novel’s belief that if selfhood is not an eternal truth but a queer fiction, then we must keep reading, writing, translating, pirating, photocopying, citing, and sharing ourselves into existence.

Shawn Hoo is assistant editor at Asymptote. His writing can be found in New Delta Review, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, Queer Southeast Asia, Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine, OF ZOOS, EXHALE: An Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices (Math Paper Press, 2021) and elsewhere. He received his BA(Hons) in Literature from Yale-NUS College and was a Teaching Assistant Trainee at the National University of Singapore’s English Literature department, and can be reached here.

*****

Read more queer-related writing on the Asymptote blog: