In the 2000s and 2010s, the great Korean-American poet and translator Don Mee Choi introduced Korean feminist poet Kim Hyesoon to the English-speaking world with a critically acclaimed selection, including Mommy Must Be A Fountain of Feathers (2008), All the Garbage of the World, Unite! (2012), and Autobiography of Death (2019). Choi’s groundbreaking work has inspired the flourishing of English translations of Korean poetry, and a new generation of Korean-American poet-translators, including Stine An, Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello, and E.J. Koh, have built on this foundation by creating translations by Kim Hyesoon’s successors. Among their notable accomplishments include the surreal terrains of Yi Won—published in Cancio-Bello and Koh’s translation of The World’s Lightest Motorcycle (2021)—and the mournful yet witty poems of Yoo Heekyung.

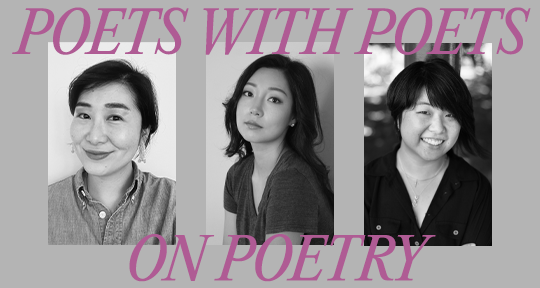

In late February, I had the privilege of speaking with these three exciting new Korean-American voices in the worlds of both poetry and literary translation, where in they radiated love for the translation process, the poets whose work they have been translating, and their mentors. One could feel the warmth in the sisterly connections they recognized between each other. For Asymptote’s inaugural Poets with Poets on Poetry Feature, in which we gather poet-translators from across the world for dialogues about their work, I talked with Stine, Marci, and E.J. about the relationship between their poetry practices and translation, the idea of “rewilding” a translated piece, and their transforming relationships to the Korean language.

Darren Huang (DH): All three of you were initially trained in poetry. Can you talk about your journeys into translation?

Stine An (SA): I was actually interested in getting into translation when I was in undergrad and taking Korean language classes; I thought that translation could be a way to “give back to the motherland,” but I was told by my mentors that you couldn’t have a career in translation. Sawako Nakayasu—a poet, artist, performer, and translator—really encouraged me to explore translation as a way to enrich my own poetry practice. I had the chance to take an amazing translation workshop with her in my final year in the MFA program, in which we were getting the traditional literary translation canon while also learning about experimental translation practices—such as translation as an anti-neocolonial mode and as a way of queering language.

But my intention for going into translation this time around was to have a different relationship to the Korean language. I grew up in a large Korean-American enclave in Atlanta, and for me, Korean language has always been tied to an ethno-nationalist identity. I wanted a more personal relationship to the Korean language as a poet.

DH: E.J., do you want to talk a bit about how you came into translation? I also know this isn’t your first text of translation because your memoir was also an act of translation of your mother’s letters.

E.J. Koh (EK): Translation, to me, feels like a true beginning. I was in a program in New York, sitting in a poetry workshop with a very bad attitude, and my teacher said if you want to write good poetry, write poetry; if you want to write great poetry, translate. That day, I added literary translation to my work.

READ MORE…