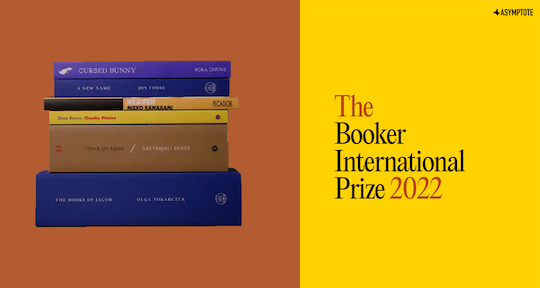

As we countdown to the 2022 Booker International Prize announcement on May 26, the contenders for the award offer new indications and perspectives by which to think about the world of literature and translation. In the following essay, our resident Booker expert Barbara Halla considers the digressive and variegated realm of “women’s writing”—that five out of the six titles on the shortlist were works by women authors is both evidence of the work’s scope and diversity, and also an overwhelming rejection of that old and tired idea: that women’s writing is simply of any gender-specific experience.

Since 2019, I have been relentlessly punished by the memory of this essay by an Albanian critic who argued in favor of the inherent superiority of men’s writing. His reasoning went like this: men write to triumph over life, whereas women write to survive. And for that very reason, the author claimed, men’s literature has universal appeal, as men are able to overcome the limitations of their own lived experiences and perspectives, while women’s writing focuses only on their painfully limited (i.e., domestic) existence.

My frustration with this article was compounded by finding its logic replicated elsewhere, in other books about the history of women in literature, and even during a conversation with another Albanian male writer a few months after reading that article. In the ensuing Q&A, the writer in question issued a complacent mea culpa about his lack of interest in women writers—he simply found their writing too limited and introspective. Of course, this is understandable. After all, it is easier to relate to Tolstoy’s Prince Andrei or Goethe’s Faust when one spends their days in the battlefield before making a deal with the devil and are whisked away for a night of debauchery with witches. After all, this is what “real” life is actually about, and it’s not like men ever write about minor concerns like marriage or childcare.

I’m being facetious, but this understanding of literature is pernicious—this desire to determine artistic value along essentialist gender lines. It also seeks to explain the existence of global and local literary canons as meritocratic, rather than the result of conscious policy decisions that have contributed to the erasure and devaluing of women’s writing. I was wondering about this argument as I made my way through the six books shortlisted for the Booker International 2022—five of which were written by women and published in the past fifteen years in South Korea, India, Poland, and Argentina. To be straightforward to the point of being trite: these five books undermine the notion that there is anything akin to a universal “women’s writing.”

Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jakob, translated by Jennifer Croft, is a sweeping history of the Jewish messianic figure of Jacob Frank, an eighteenth-century religious leader and creator of Frankism, a transgressive religious movement that lasted into the nineteenth century. Jacob’s story is told through a combination of direct storytelling, letters, and even memoirs, tracing the rise and fall of Frankism as its members sought to acquire power, property, and influence in the territories that now encompass parts of Poland and Ukraine. It is an epic tale, weaving together religion and politics, as the reader travels with Jewish merchants from the fringes of Central Europe to the Balkans and to the heart of the Ottoman Empire, portraying in intimate detail the lives and persecution of a swath of characters—mostly based on real people.

Even more epic is Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand, translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell, a story that starts with an eighty-year-old Ma in bed, reeling from the loss of her husband and retreating from her increasingly worried family. And it is in bed that she spends the first two hundred or so pages of this thousand-page doorstopper, before embarking on a journey that defies both borders and expectations. Hard to summarize in terms of plot and character, Tomb of Sand is a story about family: the small gestures that keep it together, the little betrayals (or what feel like such) that tear it apart. It is the story of Ma’s new lease on life, as she moves out of her eldest’s sons house to live with her modern daughter, makes unlikely friends, and goes through transformations that necessitate the borrowing of so many living voices to tell them in their totality. It is also a story about Pakistan and partition, about the hold the past has on us, and how history is embodied in the body and actions of one single woman.

The remainder of the shortlist is more outwardly subdued, although no less ambitious in form and the questions that it tackles. Claudia Piñeiro’s Elena Knows, translated by Frances Riddle, begins as a whodunnit with a twist: a disabled woman suffering from Parkinson’s is convinced that her daughter’s death was murder, not suicide, and she embarks on a journey to prove it. The first half of the book, however, is less about the investigation, and more a piercing depiction about trying to do the simplest of tasks (such as riding the metro) in a body you can no longer control. And if this first portion is about establishing, in a visceral way, what it means to lose physical autonomy (especially in a world that offers little support, and even less kindness), the second is about the repercussions of the choices we make about other people’s bodies. It is a clever novel with a big pay-off; the type of book tailor-made for the International Booker, revealing itself more fully to the reader with each re-read.

Mieko Kawakami’s Heaven, translated by Sam Bett and David Boyd, is also at first glance an unassuming piece of writing, telling the story of two teenagers who find comfort in one another as they go through violent and relentless bullying. I have loved Kawakami since Breasts and Eggs, in which she similarly takes on the topic of finding courage to live in a world full of pain—and the knowledge there is no other world to escape to. I like Kawakami because she is breathtakingly original, yet wears her literary references on her sleeve; the dialogues that center on important moral dilemmas harken back to Dostoevsky’s “The Grand Inquisitor” chapter in The Brother Karamazov (translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky); her ability to portray the commonplace as a disconcertingly alien is reminiscent of Kazuo Ishiguro at his best. But in grounding her characters in the “mundane” rather than the fantastical, Kawakami is ever more adept questioning the foundations of our moral convictions.

Short stories have always had it rough on the Booker International, but there is something about Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny, translated by Anton Hur, that makes me think of it as blockbuster material. Perhaps it’s the psychedelic cover that would be recognizable anywhere, or the fact that despite it having been nine months since I first read it, I can remember vividly the plot and chilling language of each story in the collection, including how it starts—with a head coming out of a toilet, or how it ends—with a woman contemplating power and control as she ties her willing lover to a bed. The images are indelible: ships floating in the air, a car sinking into the night, a village terrified by a mystical creature and a boy without memory, a father only too happy to exchange blood for silver. It is a collection as eclectic as it is compelling, playing with notions of motherhood, exploitation, and ghosts.

If short stories face a singular challenge in their Booker journey, so do books that are part of a series—consider, for instance, the concluding volume of Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels, translated by Ann Goldstein and shortlisted in 2016, or Virginie Despentes’s Vernon Subutex, translated by Frank Wynne and shortlisted in 2018. It feels wrong to call Jon Fosse’s magnificent Septology, translated by Damion Searls, “a series”—with all the baggage that the term entails. The sequence is technically seven novels in three volumes, and although only the project’s last volume—A New Name—was shortlisted, if Fosse wins, it will be for his oeuvre as a whole. While the works are not connected by narrative, they form a cohesive and moving foray into the roles that art, family, and God play in a person’s life. Written in a single sentence and in a Norwegian dialect, Septology is told from the perspective of Ales, a widowed artist working on a painting and taking care of a doppelgänger that bears his own name. The novels are a litany of fragmented memories and the small gestures that make a person’s every day, connected by Ales’s musing about his relationship to God and existence. While Septology is perhaps more formally ambitious, Fosse’s attention to the Ordinary, heightened by one’s relationship to religion, seems tailor-made for fans of another favorite author of mine: Marilynne Robinson and her Gilead series.

There is a tension in discussing women’s writing. While it is true that the gender of these aforementioned women authors cannot inherently tell us much about their work, it would be disingenuous to claim that the fact of them being women doesn’t matter. If we can acknowledge that writing in itself does not necessarily betray gender, it is nevertheless colored by experiences; it’s not so much that there is a “female sensibility” that we feel in writing, but rather that each writer’s work embodies a whole world. So what worlds have we been missing in prohibiting or dismissing women’s writing?

Women play a crucial role in almost all the books on the shortlist. The Books of Jakob is catalyzed by an octogenarian woman’s near-death at a wedding; Yente swallows a scroll meant to only keep her alive for the duration of the festivities, but that act of consuming the written word allows something like her consciousness to rise above everything, and it is through her eyes that Jakob’s story reaches us. A woman who refuses to die is also at the center of Shree’s Tomb of Sand, one who defies both man-made and natural demarcations. And, as the narrator says from the very beginning: “Once you’ve got women and a border, a story can write itself. Even women on their own are enough.”

Women abound in the short stories that comprise Cursed Bunny—a collection deeply preoccupied with the horror inherent in having an impregnable body. The notion of women’s bodily autonomy is crucial to Elena Knows, perhaps more than any other book in this shortlist, though Piñeiro has chosen astutely to build a story that emphasizes bodily autonomy period, before she turns to women’s experiences more specifically. Between the two, we understand that reproductive justice and women’s freedom is far more complex and unplumbed than the dialectics of abortion.

In showing the diversity of women’s writing—and especially if we focus on the more sweeping and experimental stories like The Books of Jakob or Tomb of Sand—it may lay credence to the notion that “good” literature is about the epic, that fiction focusing on the “domestic” is somehow a minor interjection in the serious cannon. But you have stories like Kawakami’s Heaven which start with quotidian middle school bullying, only to have you question the ethics upon which overarching life decisions are made.

No—there does not exist a common thread capable of tying together six books published in different countries, across different eras. Not even the fact that five of these books were written by women. It is this stylistic and thematic diversity, all executed with deftness and ingenuity by a crop of talented translators, which makes this a particularly hard year to predict. It might also be the first year I don’t have a clear favorite, although the last fifty pages of Elena Knows and a specific monologue in Heaven left me reeling in ways only good literature can—leaving the mind off-kilter, out of balance for days. Still, I think Tomb of Sand will win this year; it is funny and irreverent, moving and hopeful, all the while expertly blending the epic and the domestic, demonstrating how artificial the line between the two is.

Barbara Halla is the criticism editor for Asymptote. Recently, she served as co-curator for a memorial house on Musine Kokalari. Her essay on Annie Ernaux and the politics of female desire was published in the anthology Le Désir au Féminin (Ramsay Editions, 2022). Barbara holds a Bachelor’s degree in History from Harvard and is an incoming PhD student at Duke’s Romance Studies department.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog!