With the upcoming announcement of the Booker International shortlist on April 7, our in-house Booker expert is here to take you through the impressive longlist, discuss the intersection between closed-door judging and fervent public online discourses, and the increased visibility of the translator in bringing these vital titles into the English-language sphere, Read on to find out more!

The International Booker Prize, like a number of other British literary prizes, has become a unifying topic amidst a very active online community. Twitter is the kind of place where bubbles of connections and affinities naturally form, but participating in this nexus simultaneously fosters a detached sense of irony that makes any earnest acknowledgment to it a touch mortifying. I am willing to take the risk of too much earnestness today because, for the sake of honesty, my relationship to the International Booker would not be the same without this community.

I became a regular follower of the prize after attending a meeting with the judges at Shakespeare and Company in Paris back in 2016 (a discussion I left certain in the knowledge that Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, translated by Deborah Smith, was going to win, as it did). But it was entering in conversation with other readers and translators through Twitter that made the International Booker an event that I await impatiently every March. We make a friendly race out of reading the entire longlist, and debates about the merits of each selection get unreasonably heated, as we work to change the minds of others about the books we love—or even loath at times. Not to mention that I would be very happy not to have the “what constitutes nonfiction” debate again in my lifetime, which was in full swing both last year, with the longlisting of In Memory of Memory and The War of the Poor, and in 2019 when The Years was shortlisted.

Perhaps more importantly, being part of this community has shaped the approach I take the reading (and reviewing) the list. Thanks to it, I am constantly aware of the labor that goes into each book, not merely the translation but the efforts by the translators themselves, often acting as both agent and publicist. For instance, when Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights won the International Booker in 2018, Jennifer Croft had spent a decade advocating for it to be published. Furthermore, participating even somewhat actively in the discussion happening on places like Twitter is to be aware of the uneven dynamics of the publishing world. Much has rightfully been said about the International Booker’s Eurocentrism (which this year’s longlist provides a refreshing break from), but at the same time, as an online participant in these communities, you see in real time that the Booker is probably replicating trends that exist within publishing at large.

Plus, the enthusiasm of “translated literature Twitter”—to use local parlance—is deceptive; it can make you feel like translations have a wider readership than the unfortunate numbers suggest. More importantly, the very nature of Twitter, combined with the comparative smallness of the global literature community, allows the platform to bridge the gap between publishers, translators, and readers (the latter two categories being in constant flux). This solidarity, and the sense of camaraderie it creates between users, can evolve into in full-fledged friendships. I’m certain that aspects of this dynamic can easily veer into a parasocial relationship, but all nuances aside, I think this close-knitted nature becomes especially visible around the announcement of the Booker International, as people cheer not simply for their favorite books, but their favorite translators.

I am sharing this brief prelude to the actual longlist to better contextualize the enthusiasm and virtual applause that followed the unveiling of the 2022 International Booker longlist. One reason behind this happy reception is likely because this year’s list strikes a good balance between more popular titles and those that flew more under the radar. It’s perhaps a bit of an under-appreciated element in what incites personal investment in a prize, but there is much to be said about the (fleeting) feeling of accomplishment in seeing a favorite longlisted—just as there is pleasure to be derived from finding a new author or book to explore from an unexpected inclusion. It nourishes a sense of ownership, despite the fact that we had no decision-making power, nor do we know very little about what goes on behind the closed doors of the proverbial “room where it happens”—including the full list of titles that the judges had under consideration. Nevertheless, most of the judges of this year’s Booker are avid participants of this same community (in addition to being translators and book reviewers); as they shape the debates that happen among readers and in some sense, I believe they must be shaped by it in return, even if unconsciously.

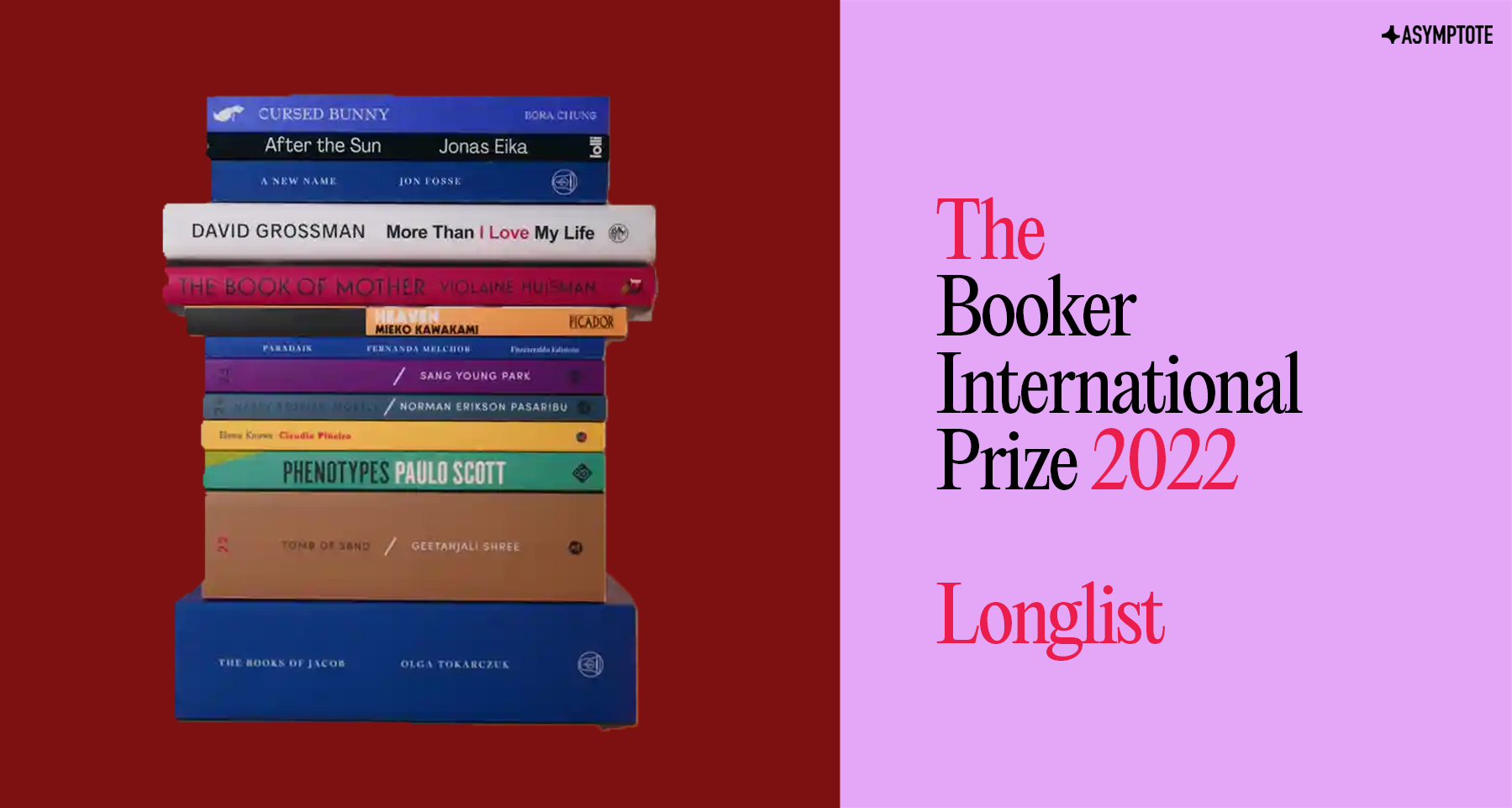

Considering the above, the longlisting of Olga Tokarczuk’s The Books of Jakob felt like a safe bet, especially given the enormous translation challenge the text represents in both length and content, it being a 900-page history of 18th century eastern Europe, and infamous religious leader Jacob Frank. The psychedelic Cursed Bunny of Bora Chung was also a predictable choice: this eclectic and magical short story collection that deconstructs systemic oppression in refreshing ways. It is worth nothing, in these two instances (but not only), that the joy on display was directed specifically towards the books’ translators: Jennifer Croft and Anton Hur, two virtual celebrities within the realm of translated literature.

In addition to being talents in their fields, both Croft and Hurhave been outspoken advocates for the visibility and rights of translators, aided by the proliferation of the “translation lit” community on Twitter and elsewhere. Last year, Croft published an article in The Guardian making an eloquent case for why a translator’s name should be on the cover. While she was not the first to voice these arguments, her article was nevertheless crucial in sparking a heated discussion on the matter, and has since aided in moving the needle in a positive direction. Meanwhile, Hur is the sharp and creative pen behind a set of essays that dissect the vagaries of being a literary translator—especially a literary translator of color in an overwhelmingly white field.

In fact, one of the more positive elements of the translated literature community is the way it centers the translator as a crucial figure in the celebration of the International Booker Prize—something the prize itself has encouraged since its 2016 reinvention. So the longlisting of titles like Fernanda Melchor’s Pradais, Mieko Kawakami’s Heaven, or Paulo Scott’s Phenotypes (all staples for aficionados of international fiction) has brought a renewed wave of support for the translators who have carried these authors into becoming “household” names within the niche of Literary Twitter: Sophie Hughes, Samuel Bett and David Boyd, and of course Daniel Hahn—whose translation diaries offer fantastic insight into the translator’s craft, as well as acting as an unparalleled resource for aspiring translators. (Speaking of Hahn, Charco Press will soon be publishing his translation diaries as Catching Fire.)

Another thorough line of the discussions surrounding the Booker International has been the role independent presses play in spreading the gospel of translated fiction. It comes as absolutely no surprise that this year, the vast majority of longlisted titles were again introduced to English readers by indie publishers: Claudia Piñeiro’s Elena Knows, translated by Frances Riddle and published by Charco; and Jon Fosse’s second entry in his A New Name trilogy, translated by Damion Searls and published by Fitzcarraldo. 2022 was also Lolli Editions’ second entry into the longlist with Jonas Eika’s After the Sun, translated by Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg. Their entry for last year, Olga Ravn’s poetic The Employees, in Martin Aitken’s English rendering, has become one of my favorite books.

But perhaps there was no better celebrated publisher this award season than Titled Axis Press with its three longlisted titles: Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb of Sand, translated by Daisy Rockwell; Sang Young Park’s Love in the Big City, another Hur translation; and finally Happy Stories, Mostly by the inseparable duo Norman Erikson Pasaribu and Tiffany Tsao. If the public were to vote today, I have an inkling this may be the runaway favorite. The two have also collaborated on the stunning poetry collection Sergius Seeks Bacchus, and the praise heaped on Happy Stories, Mostly (which includes now a shortlist for the Republic of Consciousness Prize) seems a sort of mea culpa by the literary community for letting this first title fall through the cracks.

But the cheers around Tilted Axis are concern more than the numbers, though they are impressive enough. With its almost exclusive focus on Asian writers—especially South and Southeast Asian languages—and its roster of translators of color, the publishing house has done much to tackle one of the main issues that the Booker International is often chastised for: its Eurocentric taste. Still, this is the first time that any Tilted Axis titles have been longlisted for the prize in the publisher’s six-year history.

Of course, it wouldn’t be a contemporary literary prize if it didn’t feature at least one book about a writer’s complicated relationship with their mother. And this longlist delivers on this across several titles, including The Book of Mother by Violaine Huisman, translated by Leslie Camhi, and David Grossman’s More Than I Love My Life, translated by Jessica Cohen. Grossman and Cohen have already won the Booker International once—in 2017, for A Horse Walks into a Bar.

With this incredible crop of longlistees, I am optimistic about the shortlist. In the past, I have had the sense that the short story collections acted more as fillers than real contenders. However, this year I have a good feeling that both Happy Stories, Mostly—which reclaims both myth and contemporary pop culture to build a new cultural queer canon—and Cursed Bunny could take it home, and are sure to at least make the finalists. In addition to their heft, The Books of Jakob and Tombs of Sand have in common a preoccupation with borders, and the people who defy them. However, I have a hunch thatTombs of Sand will make it to the shortlist for the innovative way it pushes us to reconsider mothers and the burden of history on individual actors. I think we might see Elena Knows also stands a good chance to making the shortlist; the book might be this year’s sleeper hit—an irresistible blend of crime thriller and literary fiction from Argentina. My other two votes go to The Book of Mother for the modern quality of its part stream-of-consciousness prose that continues to feel of the moment, and Phenotypes for its unflinching portrayal of contemporary Brazil and poignant interrogation of contemporary activism.

Barbara Halla is the criticism editor for Asymptote, where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the Booker International Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a B.A. in history from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: