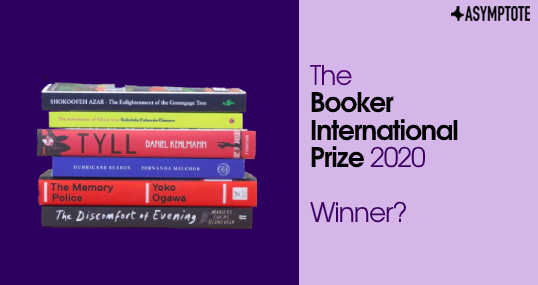

The long-awaited announcement of the International Booker winner is finally around the corner, and with a shortlist explosive with singular talent, the gamblers amongst us are finding it difficult to place their bets. To lend a hand, Asymptote’s very own assistant editor Barbara Halla returns with her regularly scheduled take, lending her scrupulous gaze to not only the titles but the Prize itself—and the principles of literary criticism and merit.

In my previous coverage of the International Booker Prize, I mentioned that there is always an element of repetition to the discussions surrounding it; quite honestly, there are only so many ways one can frame the conversation beyond mere summarizations of the books themselves. I find myself hoping that each year’s selections will reveal some sort of larger theme looming in the background, giving me at least the pretense of a cohesive thesis statement. I think that was definitely the case with last year’s shortlist and its explicit concern with memory, but considering how English translation tends to lag behind each book’s original publication by at least a couple of years, it was probably a coincidence. I’ve had no such luck with the 2020 shortlist; most of my attempts at finding a common theme have felt like a stretch.

In an attempt to avoid making this simply a collection of bite-sized reviews, I want to talk about one of my least favorite strands of Booker discourse: the tedious—sometimes almost malicious—assertion that if a particular book wins, it does so not because of its “literary merit,” but rather because it ticks a number of marketing-friendly boxes. Maybe it has been translated from a language that rarely gets published in English, or perhaps it seems particularly relevant to our present, directly tackling racism, homophobia, or misogyny. Regardless of the source of such a statement, it has this irritating “political correctness is ruining literature” thrust to it.

Now, in the past I have relied on “non-literary” clues to try and guess the Booker winner, and to some extent, I still do. However, in my mind, whenever I try to glean the winner using such external factors, I do so based on a few assumptions. First of all, while not all shortlisted books will necessarily be my favorite or even to my liking, the judges at least believe them to be great books, and the winner might indeed be different under different (personal) circumstances. In fact, despite what some detractors of contemporary fiction might say, there is plenty to love about the books being published today, and in the presence of so much good literature, taking into account “external” factors is only natural. After all, as translator Anton Hur recently tweeted, in response to an article arguing against a translated fiction category for the Hugos, “Literary awards ARE marketing tools, they should be used to solve MARKETING PROBLEMS.”

Secondly, I don’t really see political or personal relevance as extraneous to literary quality. They never have been; literary merit itself was never some vague set of stylistic criteria. The books that have come to determine the Western canon have done so because they were relevant to their time and place—because they spoke to readers about their lives and concerns. The only particularly glaring difference today is that relevance is no longer the singular domain of the white, male reader.

Furthermore, I find this sort of critique insidious for another reason—it centralizes the conversation around Western readers’ relationship to these books, and the latter’s presumed duty to educate Western readers on particular cultures or issues. This often comes at the expense of any discussion on the authors’ and translators’ craft. In June, Lauren Michele Jackson wrote an essay for Vulture tackling the question: “What is an Anti-Racist Reading List For?”. Throughout the essay, Jackson argued that designating a book written by a Black author as part of someone’s anti-racism curricula

reinforces an already pernicious literary divide that books written by or about minorities are for educational purposes, racism and homophobia and stuff, wholly segregated from matters of form and grammar, lyric and scene.

There is an analogous divide in our discussions and reviews of fiction in translation, especially non-Western fiction, exemplified by this insistence that in choosing a particular book as the winner, the judges are thinking more of its pedagogical value to the Western reader rather than the book’s achievement as a self-contained piece of art.

Granted, even this dichotomy between craft/style and relevance is dubious. Great books can be many things to different people, and they are good because they work on multiple levels, as I would argue most titles on the Booker shortlist do. Yoko Ogawa’s The Memory Police, translated by Stephen Snyder, lends itself to multiple interpretations. Published in Japan in 1999, it takes place on an unnamed island where objects are disappeared one by one, as are the inhabitants’ memories of these objects and, eventually, the inhabitants themselves. It wouldn’t be wrong to read The Memory Police as an indictment of authoritarianism: the novel’s English title is a nod to an actual organization that goes around the island to ensure compliance with the process of forgetting; those who do not forget are taken away. But Ogawa’s writing has a more metaphysical bent as well, tackling the nature of memory itself: the question of how we can be ourselves without our memories, what it means to die, or to live knowing that oblivion awaits us.

Memory and life under totalitarianism are also major themes explored in Shokoofeh Azar’s The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree. At the center of this story is a family who loses everything in the aftermath of the Iranian Revolution, and the narrative moves backs and forth in time, bringing details from the life before and after these life-shattering events. The Enlightenment of the Greengage Tree is imbued with a sense of the fantastical; there are tales of hungry djinns roaming the forests, and a girl who transforms into a mermaid after a particularly painful heartbreak. As a result, much of this book has a fairytale quality to it, relying on the lyricism of the Persian poetry it quotes at length, and making a case for both the healing and destructive power of literature and art in a time of crisis.

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara’s delightful The Adventures of China Iron, translated by Fiona Mackintosh and Iona Macintyre, is a suspiciously joyful intervention into what I would consider a rather bleak shortlist. Light infuses every aspect of this book; it is there from its very first lines, blatant as a mission statement. Seeing a young pup joyfully skimping along the dusty landscape of the Argentinian pampa, China Iron, our narrator, says: “I saw the dog and from then on all I wanted was to find that kind of brightness for myself.” The Adventures of China Iron is unabashedly queer and hopeful, but it is never naïve. The book is a spin-off of Argentina’s national epic poem Martín Fierro by José Hernández, and it directly challenges the latter’s nationalistic project, offering a critique of empire and industrialization and reclaiming Argentina’s indigenous history.

In terms of bleakness—even for a particularly dark set of books—The Discomfort of Evening made me extremely queasy. If the main characters in China Iron look at the body as a source of pleasure, in Marieke Lucas Rijneveld’s debut, translated by Michele Hutchison, the body is a source of sin, shame, and a tool for punishment. The Discomfort of Evening charts the unravelling effects of grief on an already strange (to put it lightly) and dysfunctional family. It is definitely not one for the fainthearted.

When I read the summary of Daniel Kehlmann’s Tyll, translated by Ross Benjamin, back in February, I didn’t necessarily think: “Oh, this book about a trickster out of German folklore as he makes his way through war-torn Europe is going to be incredibly relatable,” but that was February. Tyll is a fragmented affair, a historical novel told in a series of vignettes. Tyll himself is often absent, and Kehlmann chooses to focus the narrative on the ravages of war and the plague on poor communities, palace intrigue, and religious strife. Although we are separated from the events of the novel by centuries, it all feels very intimate somehow, and Tyll’s prankster nature lends this story a playful tone despite its somber subject matter.

Now, in the past, I’ve been wary of coming out with an outright favorite or giving a definitive winner prediction. I’m a sore-ish loser, so I leave my predictions ambiguous, couching them with a “maybe” or “potentially.” However, I am going to go all out this year and say that I think Fernanda Melchor’s Hurricane Season should—and will—win the Booker International for 2020. While the rest of the shortlist is more than worthy, Hurricane Season blew me away. It is an unforgiving tale about the nature of violence itself, and provides no easy answers to the uneasy questions it raises. The town of La Matosa, the murder of its witch, and its myriad of other characters culminate in perfect evidence that the abused can be abusers, that it’s easier to turn on one another than to recognize or tackle the systemic violence brought against a community. Hurricane Season grabs you by the throat and doesn’t let go; you experience it as a cascade of fear, resentment, and pain—all thanks to Sophie Hughes’s translation, which is a masterclass in the poetry of language. I would be surprised if it is not awarded the prize on August 26.

Barbara Halla is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote, where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the Booker International Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a BA in History from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: