As we inch towards the end of a year that has tested in turn the limits of our imagination, the capacities of our patience, and the extent to which we indulge our escapist tendencies, we have been encouraged to examine closely the narratives that perpetuate contemporary existence: narratives that not only exist within the pages of books, but that also thread our day to day, commanded by something as curious as it is unknown. So, in our second-to-last Book Club selection of 2020, we are thrilled to introduce a complex, mysterious, and commandingly beautiful novel by Serbian master Goran Petrović, which inquires into the infinity of literary invention in order to infer how fantasy contributes to reality.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

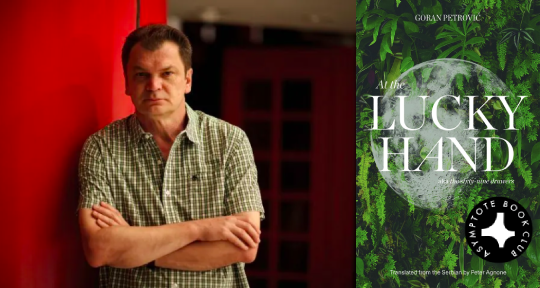

At the Lucky Hand, aka The Sixty-Nine Drawers by Goran Petrović, translated from the Serbian by Peter Agnone, Deep Vellum, 2020

Goran Petrović’s At the Lucky Hand, translated from the Serbian by the late Peter Agnone, flatters the sensibilities of those enamored with the written word—within its pages, we become romantic leads and daring detectives. Our quality of “mild presence or mild absence at the same time” becomes a virtue, nearly a superpower, highly valuable to various profiteering types. In fact, the novel is Petrović’s contribution to what might be considered the devastatingly nerdy genre that animates literary theory. And yet, this is only one face of a multifaceted work. Irresistibly engaging and virtuosically crafted, At the Lucky Hand marries high theory with high drama in spaces so quiet and invisible, that their liveliness takes one completely by surprise.

Petrović strikes a winning balance between imaginative extravagance and sober social criticism. Adam Lozanić, a somber, lonely philology student and part-time proofreader, receives a lucrative job offer from a mysterious couple; he must revise a memorial already long out of print. The book, expensively self-published, contains six hundred pages of description with no plot or characters to speak of. Adam and his employers are practitioners of a sort of reading analogous to lucid dreaming, in which they can meet other readers enjoying the same book at the same time and explore the universe of the text in all the richness suggested, not explicated, by the words. The elaborately described estate, imagined by the deceased author in a state of devotion to a love no less real for having never escaped the page, provides a ripe stage. Adam and the few other readers, thrown together by happenstance, fill in the vacuums where conventional literary elements were missing. Love, murder, mystery, power, and ambition electrify places that tremble on the edge of existence and people who, by all appearances, sit in chairs moving nothing but their eyeballs.

Jelena, characterized mainly by her pleasant smell, fervent desire for escape, and careful companionship to an increasingly senile woman, unwittingly enchants the innocent Adam. But they are only the latest lovers to inhabit the home and garden. As the stories of their predecessors unfold, frustrated precisely because of the disjunction between the realities on and off the page, one yearns for Adam and Jelena to reconcile the two. However, the more decidedly a character chooses to exist inside the literary imagination, the more they develop a noble purity outside of it. Adam and Jelena learn what the more seasoned readers already know: that they neither need nor want anything of “real” life. The very food that nourishes them is cooked in fictional kitchens and the money they exchange in long-shuttered shops appears from memories of long-defunct banks. Using nothing, they are useful to no one, and the talismans that give them access to their imaginations are the only means one has to influence them. READ MORE…