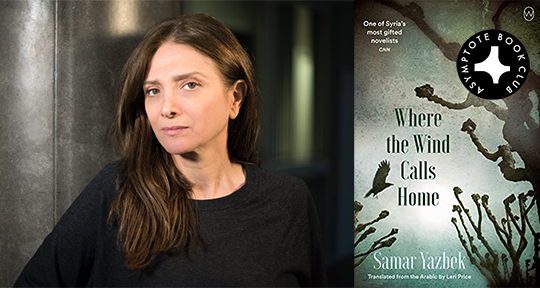

This week, we hear of a moving Palestinian work, written from Israeli prisons and recently awarded the prestigious International Prize for Arabic Fiction; newly translated short stories exploring the psychic and physical disturbances of pre- and post-handover Hong Kong; and events bringing literature to their communities in Kenya.

Ibrahim Fawzy, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Egypt

For the first time since its launch in 2007, the announcement of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) winning novel did not bring controversy, but rather warmed the hearts of those who read Palestinian prisoner Basim Khandaqji’s A Mask, the Color of the Sky (قناع بلون السماء).

Since the announcement on April 28, during the annual award ceremony in Abu Dhabi, UAE, I’ve pondered: has Khandaqji, who is serving three consecutive life sentences in an Israeli prison, realized the profound impact of his voice? Has he realized that the light he is seeking within the confines of his cell is now illuminating countless hearts? For two decades, Khandaqji has steadfastly honed his literary voice while incarcerated, as a form of resistance and a means to combat isolation. His only solace in the absence of nature’s beauty and freedom is the limitless expanse of his imagination. Khandaqji chose to walk on the fiery coals of writing, engaging in battles of resilience. Stubborn and preserving, he began his journey with literature by writing poetry (a natural start for a prisoner, as poetry is an act of freedom and a potent resistance to captivity), believing that the occupation can imprison his body, but not his free imagination or resistant literature.

Khandaqji’s family recounts the arduous journey he has undertaken, moving from one prison to another because of the arbitrary measures taken by the administration. Yet, despite these difficult and complicated circumstances, Khandaqji and his fellow prisoners managed to smuggle their literary works beyond the towering walls of their confinement, a testament to their unwavering commitment to their craft. The owner of his Lebanon-based publishing house, Dar al-Adab, shared in an interview that the novel was recorded on a pen-like device, and his brother, who accepted the prize on his behalf, was the one who painstakingly transcribed the text. Some might think that Khandaqji’s role as a writer ends only with the act of recording, but his family insists that they are keen on sending all the manuscripts to him so he can ensure that every word is in its proper place, that the events and characters haven’t been altered. READ MORE…