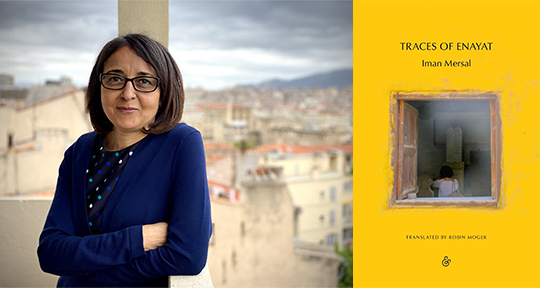

Traces of Enayat by Iman Mersal, translated from the Arabic by Robin Moger, And Other Stories, 2023

Since the ninth century, Cairo’s City of the Dead has served as the final resting place for Egypt’s caliphs, saints, poets and heroes. Their reprieve was disturbed a few months ago, however, when the Egyptian government began razing tombs in the necropolis to build a new highway. It’s a familiar trope: the uprooting of entire genealogies, the clearing away of accreting dust, all in the name of an ever-accelerated infrastructural modernity. Yet it isn’t only the dead who will be uprooted; many impoverished communities, working as morticians or caretakers, have built lives amid the deceased. Perhaps the cruellest irony is that the living, too, will be displaced in one fell swoop, sacrificed to what one writer has called “asphalt fever”.

She might not have known it then, but Iman Mersal’s perambulations through the City of the Dead in 2015, recorded in her sublimely digressive and moving Traces of Enayat, now read like premonitions of its disappearance. Primarily known for her poetry (her collection The Threshold was published in English translation by Robyn Creswell last year), Mersal is associated with Cairo’s nineties generation—a literary movement loosely characterised by a mistrust of totalising ideologies and an attentiveness to fractures in personal identity. One of her enduring themes have been to examine how exactly, if at all, the individual can be conjugated with the collective—the untraversable chasms that divide a self from another. It would not be too far a leap to connect Mersal’s quest to excavate hidden lives to Cairo’s penchant for hiding away—and obliterating—everything it deems trivial enough to forget.

Traces of Enayat resembles a biography, but is more so a catalogue of absence, a profound meditation on the limits and contingencies of the archive. Just as “there are no signs to mark boundaries in the City of the Dead”, Mersal’s hybrid work refuses the rigidity of genre. Winner of the Sheikh Zayed Book Award, it approximates the baggy shape of what she herself terms “jins jaami, a catch-all for every literary form and approach”. Julian Barnes’s famous comparison of biography to a “trawling net” is here overturned: rather than the thrashing fish hauled on shore, Mersal cares more about what has slipped away through the crevices—wanting, in fact, to document the constitution of the net itself as a “collection of holes tied together with string”. The result is a text in which theory, memoir, fiction, urban legend, and photography jostle against interleaved histories of psychiatric hospitals, marital law, golden-age cinema, orientalist Egyptology, and contested literary legacies.

All these elements are brilliantly balanced in the supple translation by Robin Moger, who is to my mind one of the best translators at work today. His exquisite sensitivity to rhythm makes Mersal’s dispassionate, crystalline voice come alive, alongside a whole host of other registers ventriloquised by the text. Having translated Mersal’s How to Mend: Motherhood and its Ghosts, Moger’s adroit familiarity with her unique cadence is evident.

The ostensible subject of Traces of Enayat is the ‘forgotten’ Egyptian writer Enayat al-Zayyat, whose suicide in 1963 left more questions than answers. While alive, she was “a branch cut off from the tree”, appearing to have avoided crossing paths with any of her contemporaries, and staying out of touch with the political climate of post-revolution Cairo. Her only completed novel, Love and Silence, was posthumously published and remains routinely excluded from conventional surveys of Arab women’s writing because it pledges no straightforward allegiance to nationalism or feminism. Mersal describes her voice as a “hesitant, melancholy, unconfident murmur, like weeping heard on the other side of a wall”—made more distinctive by the fact that Arabic was a second tongue, which she reportedly learned only in order to write. Upon her untimely demise, she was flattened into a tragic archetype, diagnosed a victim of her era—as so often befalls women writers—and then cast into oblivion. “Death in the shape of a woman,” as Jacqueline Rose wrote of Sylvia Plath.

In the sparse attempts at mythologisation that followed Enayat’s passing, the predominantly male critics conjectured that she had been crushed to the point of despair by a publishing house’s rejection of her novel. Mersal’s wry narrator (who will be referred to as Iman, to tentatively prise apart the writer from the written) finds this explanation “seductive”, but she cannot rest easy with the discomfiting gendered hierarchies enacted in the men’s portraits of Enayat, which so often turn out to be refractions of their own egos. Several claimed to have vouchsafed Enayat their support, as “high priests” of the cultural establishment benevolently admitting an unknown newbie into the “gated garden” of Literature. The whole affair reeks of something slimy, as if they had waited for Enayat to silence herself in order to have the last word, to bolster their own credentials as arbiters of artistic merit.

Driven by suspicion, rage, and an impulse to set the record straight, Iman seeks out the people that Enayat surrounded herself with. Among this cast of intimates are a range of lives illustrious and obscure; each touches off a whisper of history. Best friend Nadia Lutfi was one of the shining stars of the Egyptian cinematic firmament in its heyday; a neighbour, Madame al-Nahhas, is the “longest-standing resident” of her street and nicknamed after her parents’ associations with a former prime minister; a childhood playmate comes to Egypt as a refugee sheltered by the Jewish Hospital. Parallel to these individuals, the palimpsestic pasts of built environments—an asylum, a school, an archive—yield to Mersal’s surgical gaze. Name changes and bureaucratic rigidity occasionally pose intractable challenges, all of which Iman meets with doggedness and a flair for navigating the obfuscations of officialese.

With every person who opens their doors to Iman, new revelations about Enayat surface. She was caught in the maelstrom of an ongoing divorce case. The laws were stacked against her. A custody battle extinguished “the breath she breathed through her book”. She was not someone, after all, who could “harden her heart”. Each hypothesis presumes, in its own way, to pluck out the heart of Enayat’s mystery. In one particularly convoluted twist, a campaigner against the draconian divorce rulings cited Enayat’s suicide to advocate for her younger sister Azima al-Zayyat, who was herself pursuing a divorce in the 1960s. Enayat’s marital misery, wrought into politicised fodder, is pinpointed as the catalyst that drove her to madness: “a happy woman cannot kill herself over a book”. So was it her book, or her marriage, that became the final straw? In the light of others’ wrestling wills, Enayat herself seems “no more than a wraith”, a fragile concoction of institutional, cultural and juridical discourses ever on the verge of dissipation. The narrator notes reflexively that even now, it is the horizon of competing interpretation that has “become the real story”.

At the same time, Iman comes up repeatedly against the stony resistances of bourgeois propriety. She reckons, again and again, with the dense architecture of facts she might never be able to access. An initial fantasy she harbours of Enayat’s personal archive, packed to the brim with unpublished letters and stowed away in a mouldering attic, is soon thwarted by the discovery that most of her papers were destroyed. Secrets remain kept, antagonisms smoothed over. When Madame al-Nahhas tells Iman of a burgeoning romance between Enayat and a married young man, Iman realises that Nadia—a valuable biographical resource for all her closeness to Enayat and the picture she paints of an “unwavering friendship”—might never have been privy to certain facets of her life.

Jolted, Iman sees her own complicity in accepting a picture of Enayat as a bloodless, incorporeal creature, drained of desire and youth. One of the many miracles of the book is its insistence, nevertheless, on preserving these illusions and errors, animating them with a feeling of what it is like to believe—even if only momentarily. Against the perfect and opaque facades of class-bound decorum, Mersal reveals that writing can embody the rougher textures of real life in its enmeshment with troubled, even buried, pasts. Maybe language—just as the narrator imagines Enayat had believed—can even “force a space between pain and the one who felt it”. Where evidence runs thin, then, Mersal grants herself the freedom to fictionalise: a gesture we would likely now know (following African-American scholar Saidiya Hartman) as “critical fabulation”. Invented scenes of Enayat’s rapture at owning her own typewriter, of her walking restless rounds, cutting her own hair on the day she died, feel nearly as substantial as the hard facts; perhaps fiction is the only possible mode of witness, in the vacant face of the irrecuperable.

Something like an ethical quandary emerges from these vacillations between a “researcher’s impatient fixation” and Iman’s wish to respect “the need of those who loved her to be able to live with their pain”. Hence the reticence of Enayat’s family and friends when Iman tries to probe into the circumstances leading to her suicide—their complicity, even, in destroying the remnants of Enayat’s archives. Nadia, at one point, is likened to the consummate storyteller Shahrazad. “Dawn came at last,” the narrator says almost ruefully after a bout of enraptured listening, wanting more. What she doesn’t add is that Shahrazad’s controlled art—and maybe Nadia’s, by extension—derived from the elemental desire to live on.

Writ large, Mersal’s own narrative comes delivered in fragmented episodes, a compendium of miniature stories. They plunge us in medias res into action and break off again at suspenseful moments—as if enticing us further into voyeuristic longing. “I know you love detail,” she speaks, dreaming of holding forth before a séance of writerly foremothers. Simultaneously, she is addressing us; she implicates our desire for a good story. But we come to understand, with Iman, that Enayat’s pain is not hers to exhume—that the will to know can inflict its own kind of violence. Traces of Enayat represents, in this sense, an object lesson in how agitated phantoms can be laid to rest:

At first blush, the destruction of Enayat’s archive felt like a catastrophe, but its absence sent me after the traces of its erasure and showed me that my true ambition was not to see her life laid out in the pages of a book. In describing the life of someone who has died we inevitably become complicit in the flattening of the past, the hollowing out of meaning and complexity. I mustn’t speak in her name, I told myself; I mustn’t present some sketch version of her life. There is a moment of intersection between us and I will use this moment as a spiritual guide; in every other regard we shall be different.

I will use this moment as a spiritual guide. Iman often pauses to comment on Enayat’s gentle, sibylline hand, which sends her signs along the way and sometimes seems to want, almost coquettishly, to escape detection; she senses the warmth of Enayat’s breath, her shadow “watching over”. Prior to her efforts to unravel the knottier enigmas afflicting the novelist’s legacy, Iman was her reader. In Enayat’s Love and Silence, a character expresses a desire to “pull this self clear, gummy with the sap of its surroundings”; to “erase myself and be reborn, somewhere else, some other time”. Almost uncannily, it recalls one of Mersal’s own poems from The Threshold, where she supposes that people who commit suicide “have more faith in life than they should / and believe it’s waiting for them somewhere else”. Indeed, Iman finds herself immediately seized by Enayat’s limpid voice, her absolute incompatibility with other writers of her epoch. Their expanding affinity—which is none other than the story Traces of Enayat ultimately tells—spins out of that affective nucleus forged between writer, reader and text: an encounter chalked up to “fate, delivering a message to help you make sense of whatever you’re going through—and at the exact moment you most need it”.

Never are we allowed to forget the indelible inscription of the “I”, which moves and acts from this love. Only Mersal, embedded as she is in Egyptian social and literary networks, could have taken these turns, written this text, birthed these psychic investments. She tosses up convergences like coincidences: Nadia meets a writer taken as an Israeli prisoner-of-war, who happens to have once been Iman’s mentor; the carpenter who installed the wooden fittings in an archive that Enayat frequented is the same person who built Iman’s bookshelves. All this might be another way of saying that her search for breadcrumbs eventually pieces together a cartography of her elusive, errant self.

Aware of the biographer’s risk of vicarious overidentification with her subject, Mersal, at one point, speculatively transplants herself and Enayat into the same epoch. “The truth is that friendship between us had been impossible,” she confesses. Hence the writer disentangles herself, instead creating a space to commune with Enayat’s furtive spirit: “You are present in the alienation we both have lived, each in our time. And you are a part of the writing, which has given to us and taken away.” Just as she says I, she can now say you—an accounting of our endless debts, to the dead and to the living, to the other and to the self, to everything remaindered in between.

Alex Tan is Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: