In our global village, a great many of us have found ourselves in liminal states between cultures, countries, languages, and selves—whether in travel or in daily life. As the world becomes seemingly smaller, however, our internal universes have continued to expand and multiply, as demonstrated in Dana Shem-Ur’s penetrating and incisive novel, Where I Am—our Book Club selection for the month of June. Portraying the conflicts and multitudes of a woman inhabiting the very definition of a cosmopolitan life, Shem-Ur brilliantly encapsulates the alienations that pervade contemporary existence, tracing all the detritus of when an individual collides with place.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

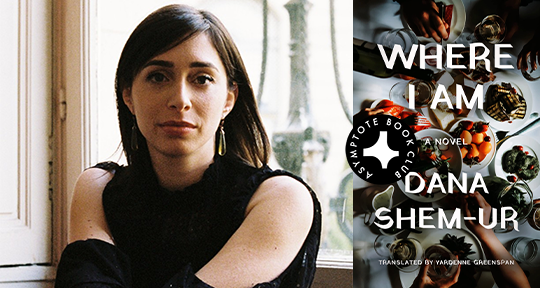

Where I Am by Dana Shem-Ur, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan, New Vessel, 2023

In the world of literature, the question of one’s own “where” takes on new dimensions. “Where” dances sinuously with class, language, education, climate, religion, politics, and more, each amorphous construct reinforcing and transforming the others, driving back the question of origin into the unknowable. The concept of “where I am” is dictated not only by the objective latitudes and longitudes of geography, but also by the subjective constructs that layer over each other—over “me” and “you.” Reut, the protagonist of Dana Shem-Ur’s Where I Am, translated from the Hebrew by Yardenne Greenspan, embodies this dance even more strongly in her position as a foreign resident and translator, amidst the confusingly cosmopolitan yet prescriptive Paris literary scene.

Reut has, in many ways, lived the ideal cosmopolitan life. She attended (though did not finish) a doctoral program at Columbia University in New York City; she lives in Paris with her French husband, Jean-Claude, a professor of religious philosophy; she hobnobs with internationally famous authors and musicians; she translates literature and studies the American Civil War with the comparative lens of medieval chivalry. Yet the very nature of her globe-trotting lifestyle means that Reut has begun to gradually lose her sense of where-ness. As her marriage unravels and language begins to fail her, Reut senses more and more how even common tongues can quickly become incommensurable walls, especially within the confines of her family. Even her son, the nineteen-year-old Julian, is unfathomable to her in part because of

Julian’s oh-so-French inflection. This was not the first time she’d noticed it, but each time it surprised her anew. In these moments, all she could hear was a foreign melody, an unending tale woven by a man with an impeccable Parisian accent, who just so happened to be her son, but could have just as easily been a stranger. . . Reut listened to him, her son—her son who thought in French, loved in French, laughed in French, and hurt in French, all of those realities that were never truly clear to her. An insurmountable barrier divided her and Julian, aspects of his soul that were beyond her.

Though Julian is flesh-of-her-flesh, he clearly takes after his father in every way: language, mannerism, Parisian aplomb. At a party the family is hosting for the internationally acclaimed Franco-Russian novelist, Mikhail Grigoryev, Julian approaches the author by appearing neither too enthusiastic nor too cool; he strikes the very same balance his father maintains only a few pages earlier, even though privately Julian professes “that Grigoryev’s style of writing [isn’t] his taste.”

Time and again, Reut is confronted with this carefully maintained civility both within and without of her marriage, exacerbated by the ways in which she contorts herself to better fit Jean-Claude’s expectations and aspirations. To him, she is not Reut but rather “Tutu,” as her real name is too difficult for him to pronounce. Their sexual encounters are for the most part monotonous, and when Jean-Claude does choose to heat up the mood, his actions are based not on Reut’s desires or bouts of loneliness but rather centered around his social conquests, as when he tries to initiate an erotic encounter in the kitchen while they are entertaining Grigoryev. Reut must never interrupt Jean-Claude’s work at his desk or trouble him when he’s tired, but when she is translating at the kitchen table (she has no office of her own, it seems) or already asleep by the time he arrives home, he sees no problem with interrupting her work or her rest.

Reut’s inability to cross the divide between herself and Jean-Claude would perhaps be more bearable if similar cultural and linguistic divides yawned between herself and perfect strangers. But out in the world, freed from the constraints of Parisian society in the form of a summer getaway to Italy, Reut finds herself connecting—albeit awkwardly—with a taxi driver named Ahmed, who picks out her accented French and divulges his family’s own difficulties with their migration to France and, unlike Jean-Claude, makes a concerted effort to pronounce Reut’s name—though he too struggles with the first syllable. Another stranger on the plane, Julie, strikes up a conversation with Reut in broken Hebrew and fluent French, and in the short flight, they exchange life stories and life philosophies. Upon touchdown, Reut reflects:

[She] loved feeling this specific fatigue, that post-conversation moment, in which both parties felt satisfied about their own self-exposure, a temporary closeness between strangers. Both would mull over insights gained, savoring a fleeting overlap of lives that soon enough diverged as before, each to its familiar path. How odd was the power of a single conversation—so brief when compared to life’s expanse—to carve into her soul another flash of memory that would surface inexplicably from time to time, carrying her forward.

These moments when Reut contemplates the ways in which language does and does not serve human connection are when Shem-Ur’s novel most shines. Shem-Ur is herself a translator, and her writing demonstrates an acute awareness of the ways in which living in a foreign country and existing in a foreign language do not so much build the oft-cliched bridge, but rather—particularly in an increasingly hostile atmosphere of anti-immigrant sentiments across much of Western Europe and the US—provide the mortar for walls both real and imagined. In these moments of extreme isolation, connection is often forged in roundabout ways and with unlikely candidates: in a taxi with another immigrant, on an international flight where all passengers are in some sense foreign, in a city flooded with international tourists.

Though she and Jean-Claude have come to Italy at the invitation of Grigoryev, Reut leaves him behind on a daytrip to Ostuni, where she is instead accompanied by Jean-Claude’s friend, the handsome Bernard. Throughout this brief getaway, Reut discovers a kind of carefree joy that she hasn’t felt in Paris in years. Neither she nor Bernard speak Italian, and Bernard’s Spanish is barely passable, yet on a quest for artisanal olive oil, they spend a luxurious afternoon in the company of another couple, Vincenzo and Angela. In contrast to the woman she molds herself to be for Jean-Claude, Reut-on-the town experiences a

. . . complete lack of control: true pleasure.

She was baffled by how much fun she was having that she laughed constantly, despite understanding almost nothing of the conversation. On second thought, perhaps this wasn’t such a mystery after all. Intimacy needed no language. If anything, language served as an accompaniment to intimacy only once it has already been established.

Greenspan’s translation adds yet another linguistic layer of intimacy and alienation to this text, which already in its pages liberally sprinkles French, Italian, Arabic, and Russian linguistic tics. Many of these pepperings go not to demonstrate that sense of languageless intimacy Reut discovers in Italy, but rather to operate performatively, as if to say, “Look at how French this person is, how Russian that one.” Just as Jean-Claude serves Grigoryev and his wife Russian rye and borscht (a cringe-worthy move that reads more as pandering than an attempt to provide the comforts of home), so too do these stray words and phrases serve as reminders of assumptions between all of these various cultures. Greenspan leaves these walls untouched, and indeed occasionally adds more walls with Hebrew. Neither does she shy away from moments in which Reut herself is alienating; Reut’s wild swings from anxiety to ecstasy and from sensual to cold sometimes pushed me away from the text, forcing me to get up and take a tea break. But, as Greenspan has written elsewhere, the translator’s job is to produce those elements which are most fundamental to the text, and in this case, even as we feel for Reut’s agonies, we are not meant to always be sympathetic to her. Greenspan does not soften Reut’s discomfort with either Ahmed or a woman in a hijab she encounters on the plane; instead, the language briefly steps inside those shoes and gives the truth of the character, a truth based in the complex realities of a cosmopolitan life.

In her physical and mental globetrotting, Reut is never quite on solid ground. She may be physically in Paris translating a British thriller, but her mind is often in America or Israel. A scent or the angle of the sunlight sends her milling through pasts scattered all over the world as she contemplates roads untaken and joys long forgotten. At times, even grounded in the present, Reut is in two places at once, entering an out-of-body state in order to observe the mask she wears in the attempt to please her intractable husband. When she arrives in Italy three days after the rest of the holiday party, for example, the sight of the Adriatic splits her consciousness as a neutron splits an atom. “When Jean-Claude finally appeared, it took her a few moments to react appropriately. She greeted him right away, of course, but it was some other, exterior Reut who did the greeting. The real Reut was still imbibing the Pugliese air and the stillness.” Reut is here, there, and also thirty years ago. She is a many-legged woman, each foot planted in different worlds and different times. And sometimes, when Jean-Claude has stripped away any and all joy and meaning with his demands, the “real Reut” is nowhere at all.

Laurel Taylor is a translator and Ph.D. candidate in Japanese and comparative literature at Washington University in St. Louis. Her writing and translations have appeared or are forthcoming in Monkey, the Asia Literary Review, Mentor & Muse, and more.

*****

- Announcing Our May Book Club Selection: Venom by Saneh Sangsuk

- Announcing Our April Book Club Selection: The Spectres of Algeria by Hwang Yeo Jung

- Announcing Our March Book Club Selection: Siblings by Brigitte Reimann