In its 22nd edition, The Amman International Book Fair ran from September 21–30 this year and featured over 400 publishing houses from 22 countries, offering a full calendar of literary activities from a reading marathon to calligraphy classes. The Union of Jordanian Publishers, established in 1989 to elevate the standing of publishing houses in Jordan, organizes the event each year under the recurrent theme “Jerusalem: Capital of Palestine”, and marks the start of book fair season across the region. The state of Qatar was recognized as the esteemed guest of honor of the fair in a symposium attended by Dr. Khalid bin Ibrahim Al Sulaiti, the General Manager of the Katara Cultural Village of Qatar (the foundation responsible for the Katara Prize for the Arabic Novel) and historian Dr. Hind Abu Al-Shaar was recognized for her contributions as a writer and academic within Jordan’s literary landscape as this year’s ‘key personality’.

The Amman International Book Fair is an immense organizational feat, a forum not only dedicated to the sale of books in the Arabic language but also an accessible discussion of literature’s role in Jordan historically and today. Inevitably, the topic of translation asserts itself, demanding rumination on grappling with meaning in a foreign alphabet and the challenges and opportunities implicit therein. When speaking with representatives of publishing houses of the broader region, the question of the quality of translations was ever-present and reflected in the events hosted by the fair and its partners.

In a Nabati poetry reading hosted by Basma Al-Alimat on September 26, Head of the Jordanian Writers and Authors Association, Alian Al-Adwan, was joined by poets Dr. Muhammad Mujawar Al-Omar, Hashem Al-Azamat, and Muhammad Al-Tura in a discussion of Nabati poetry and its translation. Nabati, or ‘the people’s poetry’, offers unique challenges to translation as an aural tradition in the Bedouin dialect dating to pre-Islamic times. Notably, Nabati poetry has historically received greater recognition in the Gulf states, but has recently asserted its cultural significance in Jordan. For me, traditions such as Nabati poetry stir up questions on when translation is appropriate. How can you capture rhyme and rhythm, the cadence of a work in another language? If you can, should you? In my view, perhaps an aural tradition that breathes within the context of a distinct lifestyle is served best in that dialect, for those within the community to understand and for those of us, unknowing, to enjoy as an aural experience. It is a rare opportunity to be privy to a reading of Nabati poetry, and a testament to the breadth of the fair’s offerings.

In a session marking International Translation Day on September 30, also the closing day of the fair, Dr. Ahmad Khabbas, Assistant Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Jordan, spoke to the notion of fidelity to original texts in translation and the loss that can be incurred when precision overtakes sentiment. He suggested translators must have a knowledge of and sensitivity to a language’s culture in order to faithfully capture the feeling of a work and went so far as to suggest that translation and translators do not merely work between languages but across periods of civilization, acting as interlocutors. If this is the case, how can translators grapple with the onus not only to serve a new language community with their translation, but the next generation of that language community? To me, this seems like an enormous responsibility and an unclear operative, and yet, the alternative is for language communities to rely on works on other cultures written from the perspective of their community, in their own language. In this region in particular, we know the ramifications of this practice, with countless examples of Orientalist ‘explorers’ providing ostensibly objective descriptions of people and places laden with implicit and explicit biases and ulterior motivations that then were used to commit severe and protracted harms.

Dr. Moayed Sharab, of the Department of European Languages at the University of Jordan, was the highlighted speaker in this symposium for his experience translating Time of White Horses (Arab Scientific Publishers, Beirut and Algiers, 2007) by Jordanian author Ibrahim Nasrallah from the Arabic into the Spanish. Notably, the novel was shortlisted for the 2009 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, and details three generations of a Palestinian family living within the contexts of Ottoman rule, the British Mandate, and the Nakba respectively. Dr. Moayed Sharab spoke on the difficulties of representing the human aspect of an historical tale, especially in regards to the relationships between the family and occupying forces. Director of the Translation Center at the University of Jordan Ola Mesmar added that translation allows for the exchange of ideas across languages, ethnicities, and beliefs in a globalized world.

Evident in the organization and events of the fair this year was the emphasis on educational texts, especially those for children. Publishing houses with a focus on young readers were grouped together in a section of the exhibition that was popular amongst parents of little ones, and school groups congregated around tables stacked with fantasy and science fiction from Jordan and the Arabic-speaking world, as well as in translation. A reading marathon, held in partnership with the Abdul Hameed Shoman Foundation, encouraged readers across Jordan to partake in a collective endeavor to read as many pages as possible in a day. In Aqaba, approximately one thousand visitors engaged in the marathon and read over 4,000 pages collectively.

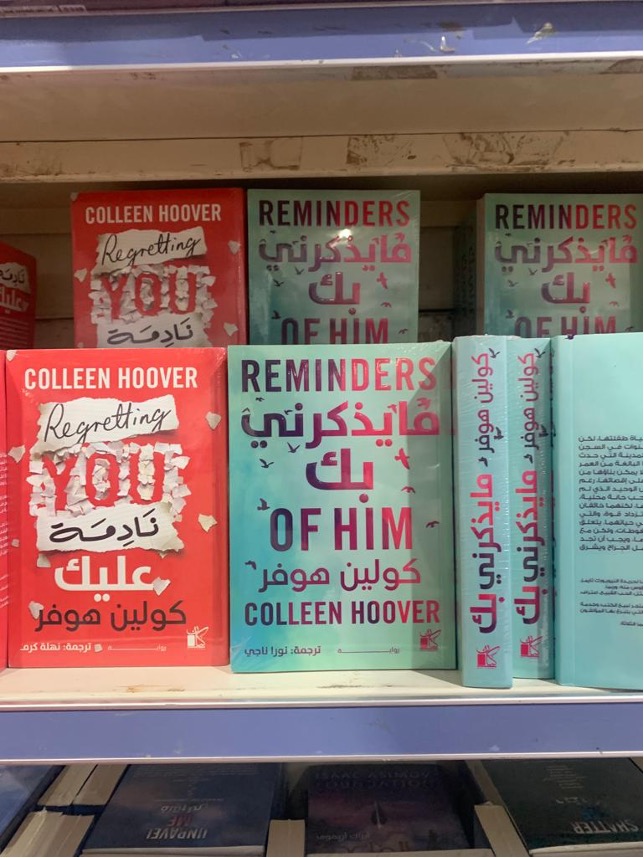

The fair was deemed a success, attracting over 500,000 visitors and witnessing an increase in sales over last year’s fair, despite scheduling conflicts with the start of the academic year for some schools in Amman. As a student of the Arabic language and a reader of its literature, the book fair was an opportunity for me to see the state of publishing in Amman of classical and contemporary texts and to speak with those working in this field on matters of translation. I was interested to learn that, according to various publishing houses, the quality of translation between the English and Arabic—in both directions—is unreliable, and a certain level of discernment is required for a reader to find a work in translation that reads fluidly. Because I was perusing titles at a book fair, and not a bookstore, I was steered towards and away from certain titles for this reason by knowledgeable publishers. This made clear to me the value in speaking with publishers directly, who have long standing relationships with their authors and translators, when seeking greater understanding of translation between languages.

Bridget Peak is an art educator from Montana, USA. Presently, she is a CASA Fellow studying the Arabic language in Amman, Jordan and serves as a digital editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: