This week, our writers bring you news from Palestine, Hong Kong, and Malaysia. In Palestine, the world has been remembering the renowned writer Mourid Barghouti, who passed away this month; in Hong Kong, Dorothy Tse’s first novel to appear in English, Owlish, will be released by Fitzcarraldo Editions and Graywolf Press; and in Malaysia, two new anthologies celebrate Malaysian writing. Read on to find out more!

Carol Khoury, Editor-at-Large, reporting from Palestine

If it weren’t for COVID-19, the narrow streets of Deir Ghassana would have been jammed with mourners on Valentine’s day. Just like many other villages around the world, Deir Ghassana—the small serene village to the north of Ramallah in the central hills of Palestine— usually celebrates Valentine’s day, but not this year: for Mourid Barghouti passed away.

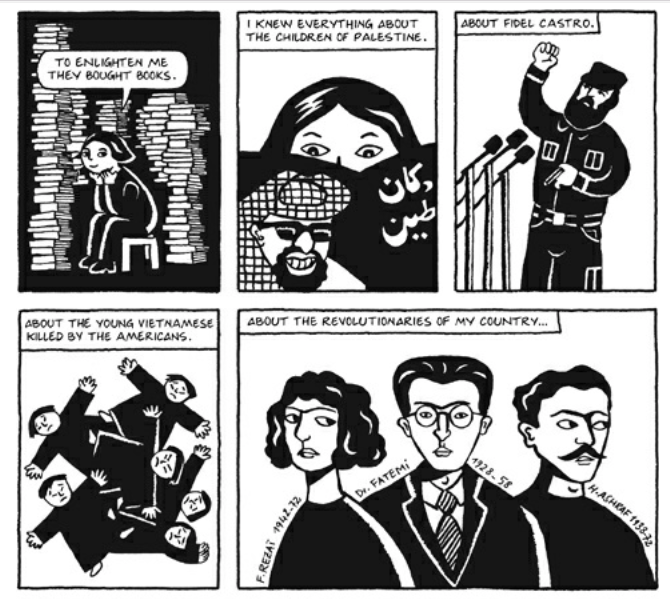

Born on a hot day in July 1944 in one of the village’s old houses, Barghouti grew to become a beloved Palestinian poet, performer, public speaker, and memoirist, albeit living most of his life in exile. He wrote the popular memoir I Saw Ramallah, which chronicled his return to the West Bank in 1996 and was translated by novelist Ahdaf Soueif. He also wrote a follow-up memoir, I Was Born There, I Was Born Here, which tells his story from 1998 to 2010, translated by Humphrey Davies. He published more than a dozen collections of poems, and a collection of his work, Midnight and Other Poems, was translated by his life partner, the great Egyptian novelist Radwa Ashour (1946–2014).

In his foreword to the English version of I Saw Ramallah, Edward Said wrote of Barghouti’s treatment of loss experienced in exile that, “it is Barghouti’s extended rebuttal and resistance against the reasons for that loss that endows his poetry with substance and gives this narrative its positive valence.” The loss of such a writer is great, but Barghouti will always be remembered. His legacy is extremely rich, not only because he was one of the most articulate defenders of the Palestinian cause, but because his writing has encapsulated the collective agony and sumoud (steadfastness) of the Palestinian people everywhere.

In his memoir, Mourid writes about the loss of his private days—his birthday and his anniversary—as author Ghassan Kanafani was assassinated on the date of the first, and cartoonist Naji al-Ali on the second. It seems life is only determined to keep the legacy alive. Sadly for Mourid and Radwa’s only son, the poet Tamim Barghouti (b. 1977), February 14 will be a different celebration from now on.

To get a taste of his writings, a collection of his translated works is published on ArabLit and a wide-ranging interview by Maya Jaggi, published in The Guardian (2008). READ MORE…