This month, we are taking a look at works from world literature that unveil the universal intersections at the centre of society: an empathetic interrogation into the cross-section of contemporary life in a superstore by the inimitable Annie Ernaux; a brilliantly curated selection of humanist stories from the Swahili; and a subtle, delicate look into the nature of happiness as written into dialogue by lauded Polish author, Marek Bieńczyk. Read on to find out more!

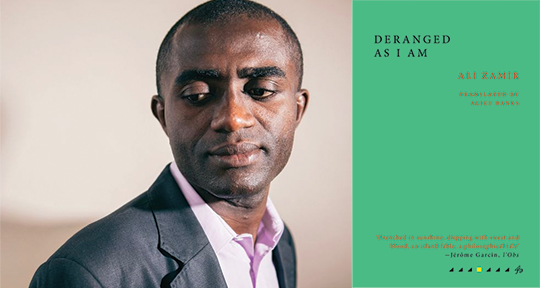

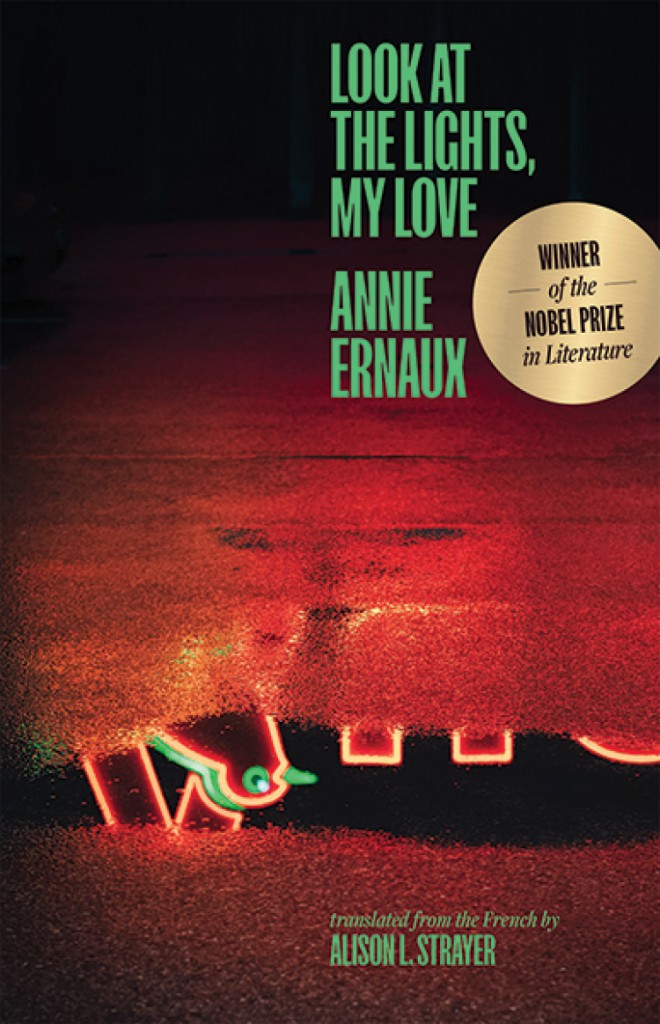

Look at the Lights, My Love by Annie Ernaux, translated from the French by Alison L. Strayer, Yale University Press, 2023

Review by Laurel Taylor, Assistant Editor

Even at its best, ethnography is an ethically tricky subject; at its worst, it can dehumanize, tokenize, and Other the people who fall under its burning eye—an eye so often situated in wealth, power, whiteness, and patriarchy. Annie Ernaux is all too aware of the treacherous ethnographic ground she walks in Regarde les lumières mon amour, originally published in 2014 and translated now into an incisive and unadorned English by Alison L. Strayer as Look at the Lights, My Love. In this brief but gripping nonfiction entry, Ernaux records her various visits to the French big-box store Auchan from November 2012 to October 2013, a period which happens to coincide with the 2013 Rana Plaza building collapse in the Savar sub-district of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

For all its drab ubiquity and late-capitalist imbrication, Ernaux treats the site of the superstore not only as a place perpetuating a unilateral and devastating economics (in the broadest sense of the word), but also one which engages humanity in complex ways—affectively, socially, temporally.

. . . when you think of it, there is no other space, public or private, where so many individuals so different in terms of age, income, education, geographic and ethnic background, and personal style, move about and rub shoulders with each other. No enclosed space where people are brought into greater contact with their fellow humans, dozens of times a year, and where each has a chance to catch a glimpse of others’ ways of living and being. Politicians, journalists, “experts,” all those who have never set foot in a superstore, do not know the social reality of France today.

Indeed, it feels almost taboo in the often inward-facing world of Parisian literature to engage with something so blasé as a big-box store. At one point, Ernaux even says in an aside, “I don’t see Alain Robbe-Grillet, Nathalie Sarraute, or Françoise Sagan doing their shopping in a superstore; Georges Perec yes, but I may be wrong about that.” For me, this is what makes Ernaux’s earnest attempt at engagement all the more relevant (and close-to-home, as I grew up in a squarely middle-class family that did most of its shopping at a big-box store). In addition to the unconventional topic, this particular book also feels difficult to classify. Neither journalism nor something so structured as a dialectic, Look at the Lights, My Love is something more akin to mindfulness. It is an attempt to deliberately undo the asynchronous pace of the superstore—a place where flash sales, labyrinthine design, ever-changing displays, and the press of daily chores all collude to entrap and entangle us in the past, present, and future all at once. Ernaux’s thick descriptions, in trying to circumvent these snares, work to better provide us with “[a] free statement of observations and sensations, aimed at capturing something of the life of the place.”